Oberhausen & Ann Arbor 2017

Ann Arbor Film Festival

Yuan Guang Ming is a major Taiwanese artist, though his work is rarely seen outside Taiwan. His films and multi-channel installations are ingenious combinations of engineering, set design, and production/post-production technologies. The cinematic works frequently explore camera movement, for which Yuan constructs elaborate crane mounts and zip-lines to travel along narrow passageways, over wide open land- and sea-scapes, and through impossible openings. In several of his projections, the camera’s motion through space is so effortless that the viewer has the vertiginous feeling that the laws of physics, of gravity, friction and momentum have been suspended. It is more intense than an amusement park ride, since Yuan layers a political and social consciousness onto the sense of liberation from physical laws.

Tom Schroeder The Sparrow’s Flight (2016) is a memorial for Schroeder’s collaborator Dave Herr who died of a brain tumor in 2009. Tom and Dave began making films as teenagers, shooting with a super-eight camera and using Dave’s father’s barn as their studio. The Sparrow’s Flight was pieced together largely from files left in Herr’s hard drive. It documents the development of the collaborators’ increasingly sophisticated technique, starting with stop frame animation enabling Dave to fly around the barn like a huge Dodo bird, and continuing through elaborate scenes produced during his illness and up to his demise.

America for Americans (2017) by Blair McClendon is centered around a re-viewing of the tragic images that have become unsettlingly familiar, of young black men being shot or strangled or beaten or sprayed with poison by policemen. These scenes are intermixed with non-violent and joyful aspects of African-American culture. McClendon’s film refreshes these images by the use of techniques borrowed from the avant-garde cinema, such as repetition, looping, multiple windows, superimpositions, and the strobe. By incorporating the experimental film techniques, McClendon succeeds in conveying the rage a young Black American feels at coming of age in a society that still fosters institutionalized regressive policies to demean and ghettoize his culture and race. If often painful to watch, the film is stimulating in its brilliant re-appropriation of tropes developed during the last 50 years in the world of experimental cinema.

Pat Oleszco’s Quit Draggin’ (2017) is a solo performance by the artist with her usual outstanding props, costumes and video. It included engaging the audience in call-and-response chants from recent demonstrations including “What does democracy look like?” “This is what democracy looks like!” and a suspended Trump blowup doll which she kicked around the stage like an old pillow.

Irina Patkanian’s feature Socrates of Kamchatka (2017), is described as the recent history of Russia from the point of view of Socrates the horse. A brilliant premise, but it’s not quite carried through. The horse is in the film, certainly, but it is rarely Socrates’ point of view to which we are treated, at least in the cinematic sense. The film is revelatory nonetheless, providing a graphic and forceful description of the changes in Russian society from within a small community.

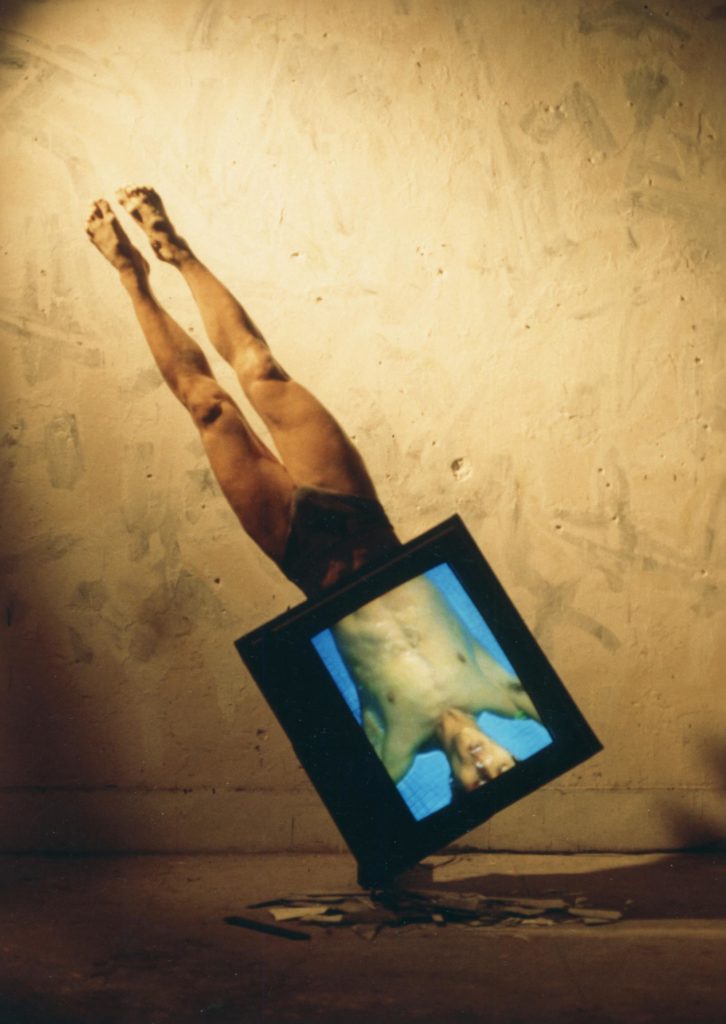

Joiri Minaya’s Siboney (2015), isa record of a performance. Over weeks the camera records the artist painstakingly painting a large, repetitive, gorgeous flower mural based on a fabric print pattern. Then, wearing a wet white dress, she destroys the painting, smearing the paint on the canvas with her body, and coloring the dress a drab brown and black in the process. Siboney functions as a metaphor for the post-colonialist exploitation and demolition of the culture of the artist’s home country, and at the same time it is a statement of the connection between painting and performance as initiated by Carolee Schneemann and other recent artists.

Brian M. Cassidy’s and Melanie Shatsky’s Animals Under Anesthesia: Speculations on the Dreamlife of Beasts (2016). This work is exactly what its title promises, a production tour de force, based on the filmmakers convincing a vet to allow them to record animal surgeries, during which they speculate cinematically on what might be going on in the mind of the dog or cat while it is ‘under.’ The premise licenses the filmmakers to shoot wild moving camera and low angle images, but the surprise of the film is a scene of a hairy micro pig exercising on an underwater treadmill in a kind of aquarium. Not a common image, even in a non-commercial experimental film festival.

Right: Irina Pathavian, Socrates of Kamchatka (2016), frame enlargement. Courtesy the artist.

Oberhausen Kurzfilmtage

The eye-opening Thema, “Social Media Before the Internet,” curated by Tilman Baumgärtel, was comprised of six programs: 1968, Video Activism, Television and Satellite Projects, Open Access Channels and Pirates, Mailboxes and Online Networks, and Taking Part is Everything: TV activities from the 60s to the 90s. The series of lecture / screenings demonstrated that the social media of the 21st century have deep roots in an pre-digital era, especially in works initiated by artists and artist collectives. For me one of the most compelling pieces was a video discussion between Nam June Paik and Josef Beuys, with Douglas David as a kind of moderator, recorded at the Feldman Gallery in New York City in 1974. Each man overlaps and strives to outdo the other in a kind of subversive outrageousness competition. Also of great interest were early works by the 1968-ers, including The Words of the Chairman, a fascinating 1967 film by Harun Farocki, made while he was a second year student at the German Film and Television Academy, and Cristina Perincioli’s dramatic film For Women—Chapter 1 (1971), about a strike by supermarket workers, with the roles played by actual shop assistants and housewives. This series of programs was by itself enough for a mini-festival, but in the context of Oberhausen it was only one small element.

Of the individual filmmakers I was most struck by Nina Yuen’s two programs and Khavn’s screenings and installation. Khavn is 40-ish Filipino artist who has already made over 100 feature films and dozens of shorter films. He appeared in brightly colored print jackets, dyed hair, great jewelry and sunglasses, a phenomenon in himself, hardly reflecting what one imagines of the land of Duterte with its rash of street killings of drug users implicitly encouraged by the tough guy president. Khavn is also a fashion designer and musician, and describes himself as the best barber in the Philippines. Indeed there was a barber shop embedded in his installation where I watched as he and an assistant were giving a brave blindfolded volunteer an asymmetrical haircut—–actually the assistant was doing most of the cutting, with Khavn contributing an occasional snip here and there.

Khavn’s films may appear crudely made, but on extended viewing one sees that this is a deliberate strategy, since they take advantage of highly sophisticated technique and technology. Far from naive, the films tend toward slightly incomprehensible narratives, which in both style and substance give a first-hand view of life in the slums of Manila. The early films are self-narrated quasi-early-YouTube pieces, except that the backgrounds are quite unlike the middle-class teenage bedrooms that characterized the platform. The first film on the program, Memory of Dawn (1996), consisted of Khavn naming everything in his environment, including furniture, pots and pans, parents, and siblings—as if he was assembling the database from which, as filmmaker, he would later draw his work. The contrast between the environments and the techniques enabled by analog and digital video technologies is striking. The availability of hi-tech tools has opened windows into parts of the world not previously easily accessible. The states of mind of the occupants of these environments and the kinds of situation depicted, as well as the methods of depicting them, are unfamiliar and revealing.

The American filmmaker Nina Yuen presented two programs of her works. My first impression of her films, one of which I had seen in the previous year’s Oberhausen festival and commented on in MFJ No. 64, is their elusiveness. While apparently too much information about the artist is revealed, simultaneously one has the feeling that nothing is revealed. It is not exactly that they are fictional, more that they are make-believe, driven by desire.

A number of Yuen’s films are built on voice-overs appropriated from a variety of sources, including reviews and criticism from high-end magazines such as the New Yorker, PBS television shows such as Animal Planet, and recent poetry. The authors are listed at the end of each film. This technique is analogous to the re-contextualizing of archival footage to reveal new meanings, as practiced originally by Bruce Conner and extensively in the 21st century with the extensive on-line availability of material of all types. In speaking the texts and performing the indecipherable, absurdist, or ritualistic actions they inspire, Yuen assumes a character with unstable, inconsistent, multiple identities. Since she speaks in an nontheatrical, confessional style, we take her on-screen persona to represent aspects of the artist herself. However, she performs a troupe of invented characters with unworldly habits and forms of behavior, as if beset with symptoms of yet-to-be-classified neurological aberrations. An elusive identity is portrayed, variable, unsettled. It is a unique approach, a fresh, instructive and inspiring use of archival material in artists’ moving image. Nina Yuen’s oeuvre is unsettling, speaking to the position I express in my review of the two festivals in the print edition of MFJ No. 66. As a body of work, Nina Yuen’s films challenge the notion of fixed individual identity, developing this idea to give a philosophical picture of personhood as multi-faceted, interwoven with stable elements but fluidly characterized by inconsistencies. It represents an intuition of particular relevance to these difficult times.

Images at the top of the review:

Color image: Joiri Minaya, Siboney (2017), performance still. Courtesy the artist and Colección Eduardo León Jimenes de Artes Visuales, Santiago DR.

Black and white image: Blair McClendon, America for Americans (2017), frame enlargement. Courtesy the artist.

Text by Grahame Weinbren