NYFF62 CURRENTS: Program 4: Space Is the Place

Under the loose thematic banner “Space Is the Place,” the six films comprising New York Film Festival’s Currents Program #4 experiment with the boundaries of the cinematic medium and expand its template of techniques. The actual spaces/places the program evokes surface more in some of the works than others, but if nothing else, a metaphorical notion of space binds the group together.

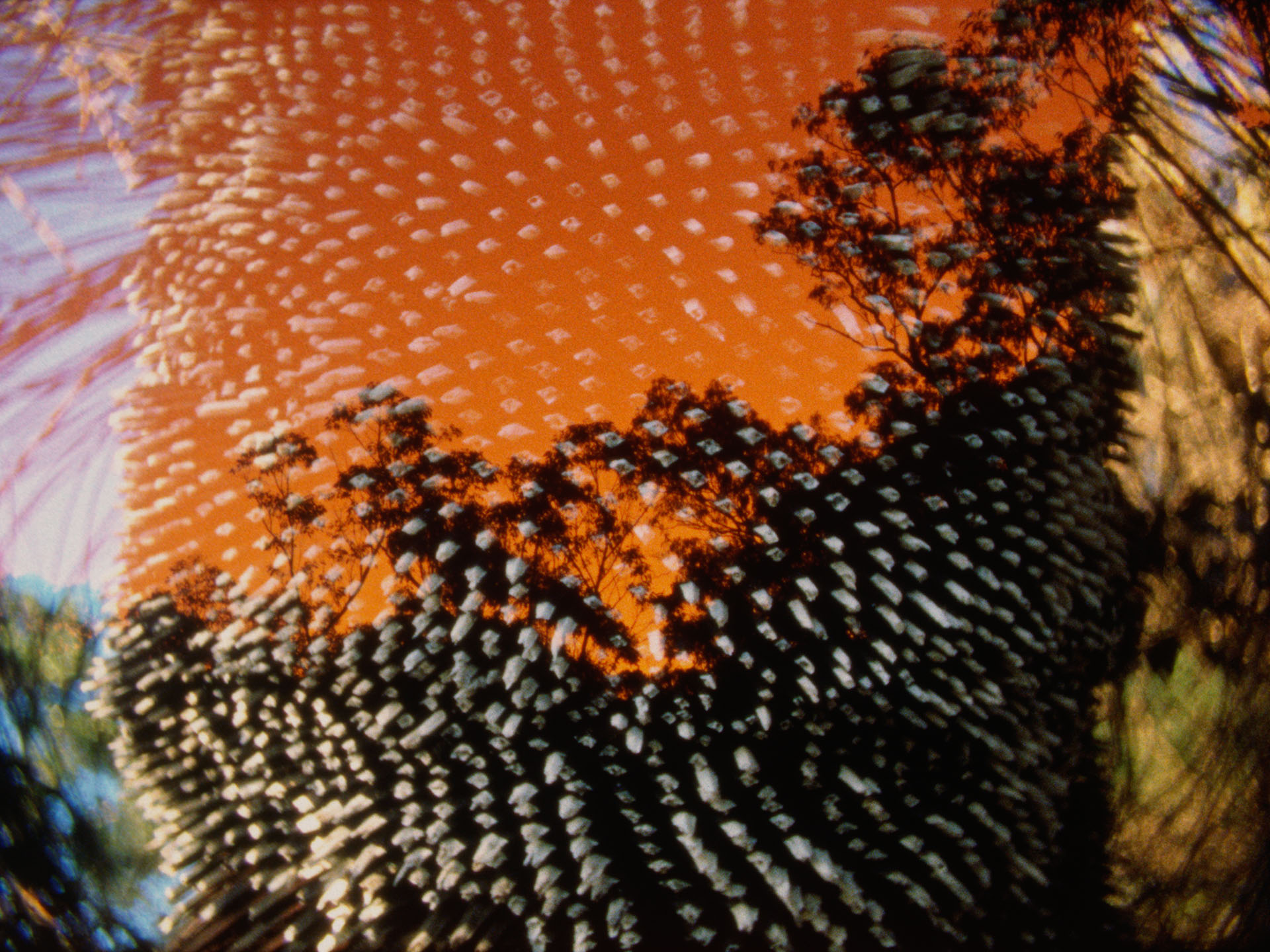

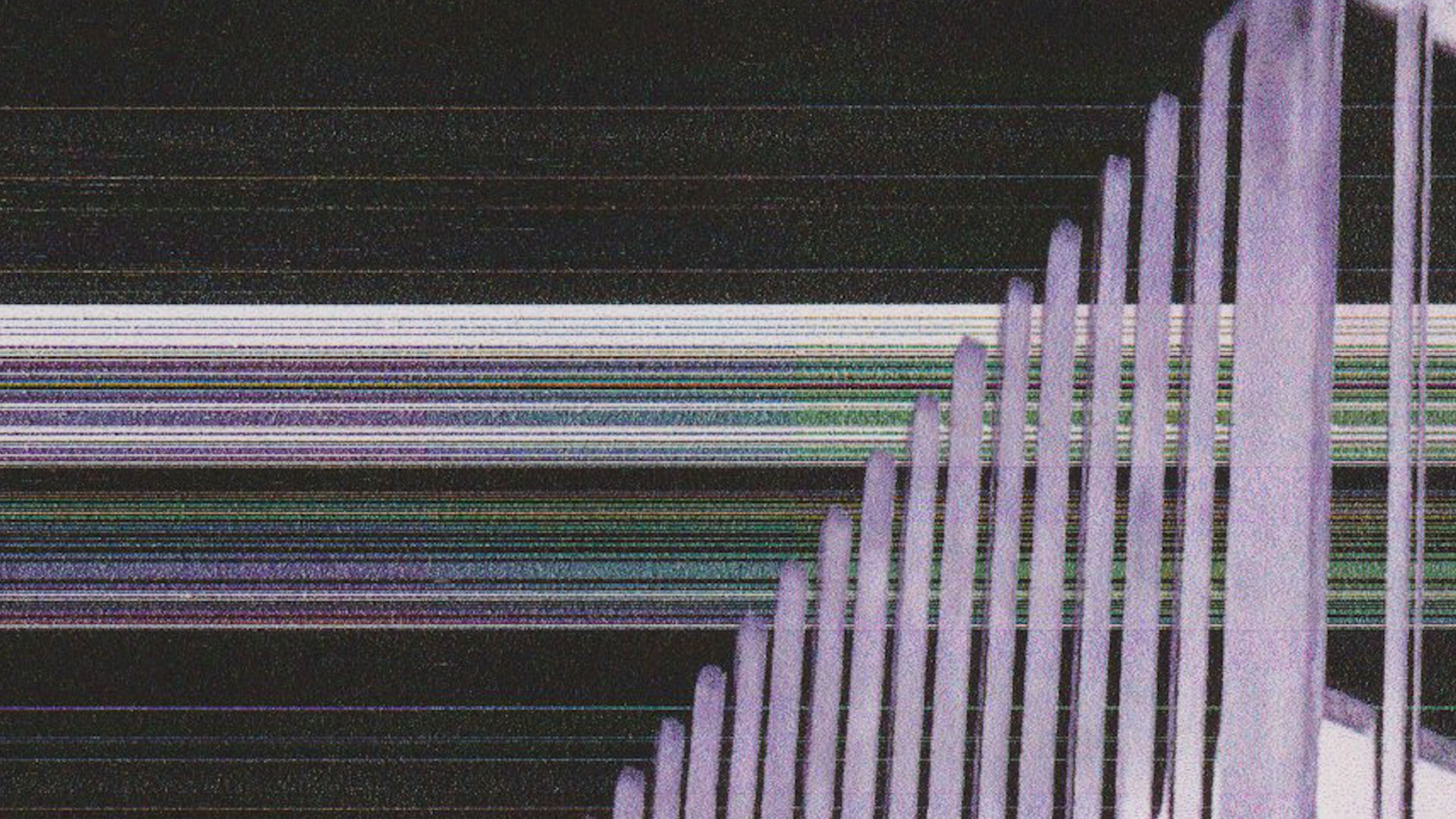

Both Malena Szlam’s Archipelago of Earthen Bones—To Bunya and Richard Touhy and Dianna Barrie’s The Land at Night situate their works in the otherworldly aspects of specific Australian locations. The former addresses the landscape of the Gondwana Rainforests, superimposing distant vistas with defamiliarizing close ups of the geography it records; the latter casts the expanses of a variety of empty spaces in twilight, signaling but eluding human presence. Both also use forbidding soundtracks to undermine any urge to contemplate the sublime aspects of their subjects. In a similar vein, Laura Kraning’s ESP fixates on another specific location: Albany’s Empire State Plaza. The images it captures likewise produce a sense of disorientation rather than a clear map of a real site. The architecture on offer in the plaza is animated with the help of a faulty inkjet printer and is presented too close, at angles, and/or with varying degrees of stuttered motion, often with printerly lines at cross-purposes, so that a horizontal grid appears just when the verticality of a tall building might be aiming to impress its observer. Here, as with Rhayne Vermette’s A Black Screen Too, the repetitive, rhythmic (not to say musical) soundscape underscores a sense of non-location inherent in these works. That is to say that their motivating interest seems to lie elsewhere than in place. For each of the six works in the program, meaning resides at least equally if not more so in an engagement with their chosen techniques. The medium’s expressive capacities (several mobilized in genuinely innovative ways across these films) constitute both the method and foundation of the works. Such is the case, too, in Lei Lei’s film re-engraved, which puts a roving camera at the service of discerning cinematic parallels to the traditional engraving techniques he documents.

In the most impressive of the program’s films, the merger between technique and meaning yields deeply moving studies of their subjects. ESP’s “collaboration” (credited as such in the film) with an inkjet printer (a wonderful fetishization of an obsolete technological object that nevertheless continues to function creatively here) as well as Szlam’s meditation on luminous yet disconcerting natural surfaces both hinge on their effective interplay with the technology/technique employed. Meanwhile, the ultimate expression of these concerns arrives in Christina Jauernik and Johann Lurf’s masterful, exquisite 3D film Revolving Rounds, which puts its own technical dimensions (literally) on display, front and center.

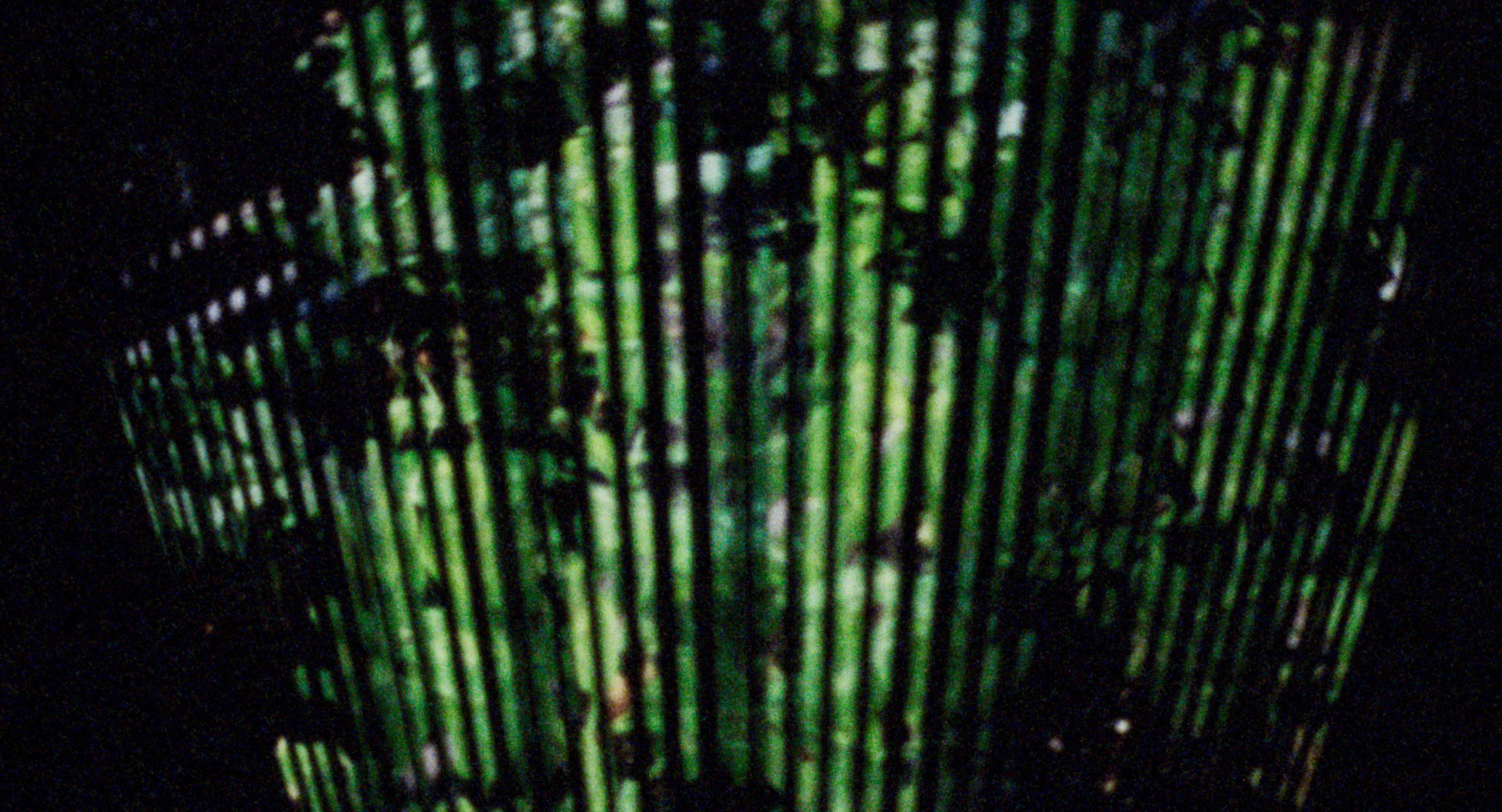

The film begins with eight slow-moving shots scanning arable land dotted with a row of greenhouses in the near distance. Each successive cut extends the movement across the horizontal axis and shifts to a close but different angle, slightly expanding the view on the same location. At the same time, the 3D cameras stretch the foreground, such that it breaks across the proscenium space into the audience. Eventually, the camera covers the distance of the fields as it edges closer to the threshold of one of the greenhouses, inside of which sits, lonely as a cloud, a cyclostéréoscope. Film enthusiasts who may be (very reasonably) unfamiliar with this early 3D technology would nevertheless have a sense of its connection to other pre- or early film technologies—the zoetrope, perhaps—or at least understand that this glowing machine with wavering dark vertical lines dividing its light has something to do with the aspects of perception and point of view already laid out in the opening series of shots. The sound of the projectors (off to the side in the vast, empty room) further solidifies this impression. From the first shot until the moment the camera has closed the distance between the open door and the cyclostéréoscope, the early light of morning gives way to darkness, which offers the perfect cinematic atmosphere for working out some questions regarding the observer, the observed, and the apparatuses that mediate between the two.

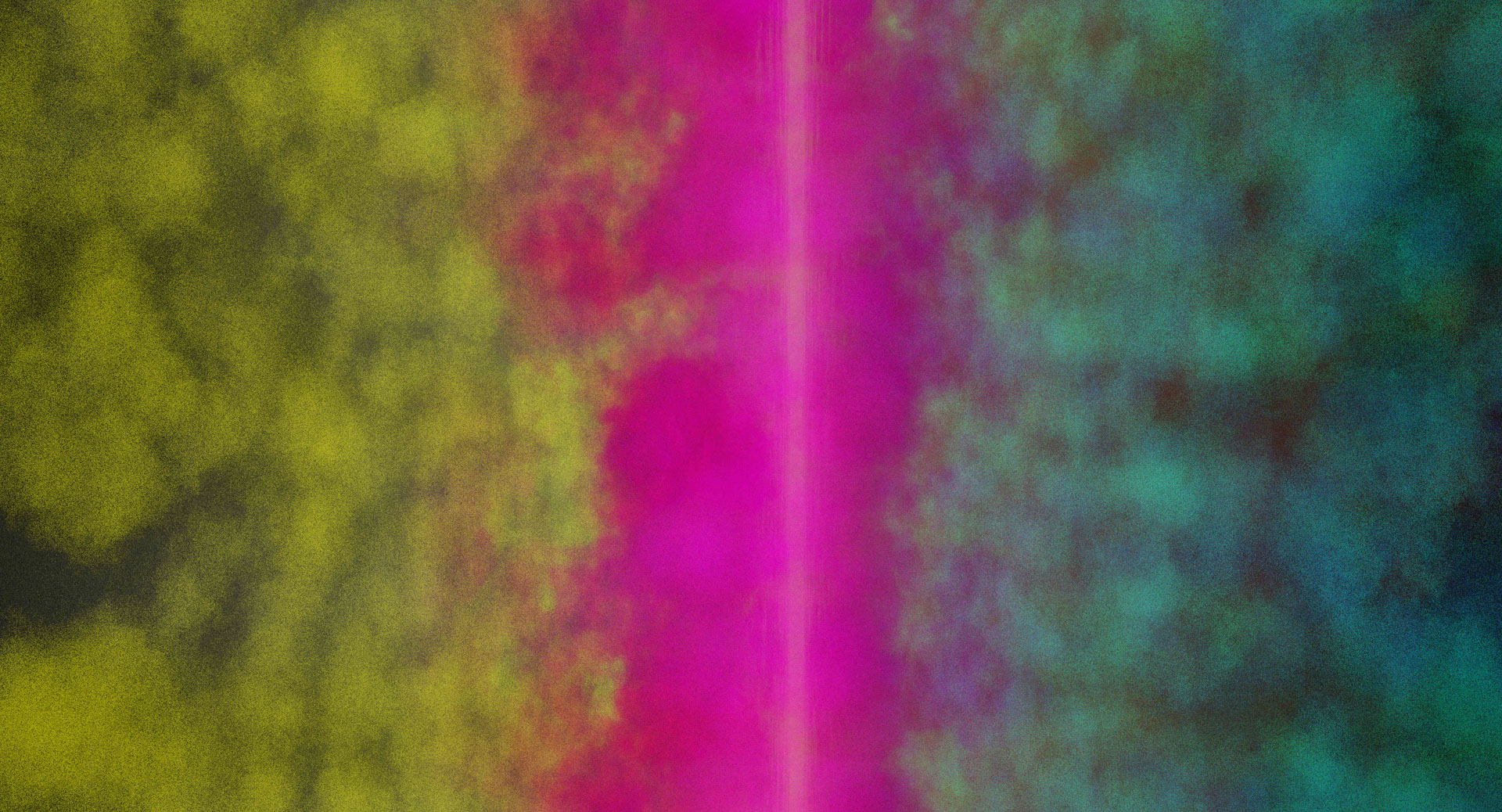

The second beat of the film continues this floating movement from distance to closeness. On the device, a projection of something leafy and green appears: a patch of pea plants. At first it presents the image in a wide view, and its mediated qualities are abundantly evident, with sound and image both clearly generated by virtue of the apparatus. The image becomes increasingly clear, its mediation less and less discernible, before it unexpectedly defies all perceptual limitations by seeming to penetrate impossibly far into the very molecules of its organic material. The image divides into bands of vivid color (fuchsia, gold, turquoise, red), depicting the breaking down of the visible material into its usually inaccessible abstract components. The projector’s sound continues to assert itself, highlighting the cinematic situation that makes this view possible. Finally, the incredible, imperceptible depth of the object is made legible at a molecular level. For the last moments, the filmmakers return outdoors and these abstract shots dissolve into a long view of the land around the greenhouses again, the brilliant star of the Earth’s sun shining beams of light over them and in every direction.

The result is a film that defies explanation: it simply astonishes. Somehow the film accomplishes everything you never knew a film was meant to do. Through its harnessing of light in sun-blinding lens flares, its vertigo-esque expansion/compression of space, and especially its tour-de-force gradual extreme close-up, it most fully and gratifyingly expresses the merger on display for the Currents program between the technologies of the medium (here: past, present, and future) and the perceptual themes it explores (here: to see as one suspected only a god might). Revolving Rounds is something to be experienced, that rare film that demands a specific cinematic context for the full expression of its remarkable power. That experience is everything: a perfect articulation of what cinema can do to further our experience of the world.

Review by Sarah Keller

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.