NYFF63 CURRENTS: Program 3: Common Ground

Lucas Kane, Jacob’s House (2025), frame enlargement. Courtesy of Film at Lincoln Center.

Like the name suggests, NYFF’s Currents Program 3 – ‘Common Ground’ represents films which all have something to do with claim to property, land, or a commonality across land between people. Lucas Kane’s Jacob’s House, which focuses on Jamaican immigrant artist Jacob Eye, is shot on 16mm film that feels as warmly textured and soothing as Jacob’s soft and mannered personality. The film depicts over a period of time the increasingly barren and desolate landscape of the multi-story property in the quickly gentrifying neighborhood of Fort Greene, Brooklyn that Jacob fights to remain in. There is an ongoing feeling of tragic decay in the film – walls progressively peel off, dust and gravel accumulates on the floors, stairs are broken piece by piece and spaces turn increasingly hostile and dark. Jacob narrates through these changes, like a diary, his own feelings under his landlord’s increasingly vicious tactics – he freezes in winter as the heat is shut off, he is unable to bathe or use the restroom once the water pipes are broken, hired intimidators come in to tear apart the walls and floor boards and threaten to destroy his artworks.

Even amid the dilapidation, Kane’s camera encourages us to imagine a better reality for the space, filming in golden sunlight and highlighting the lush greenery of the back garden. He makes sure to film the good times too. A small gathering shows various artists and collaborators and friends looking at the curated selection of Jacob’s paintings hanging on the walls, marveling at the colors and textures, taking pictures, laughing, smiling. Over it, Jacob melancholically paints a picture of the space’s past vitality, where poets would sit and write on the stoop, musicians would talk theory in the garden, painters and fashion designers and visual artists would share ideas and stories in the various rooms. “It was a community,” he sighs.

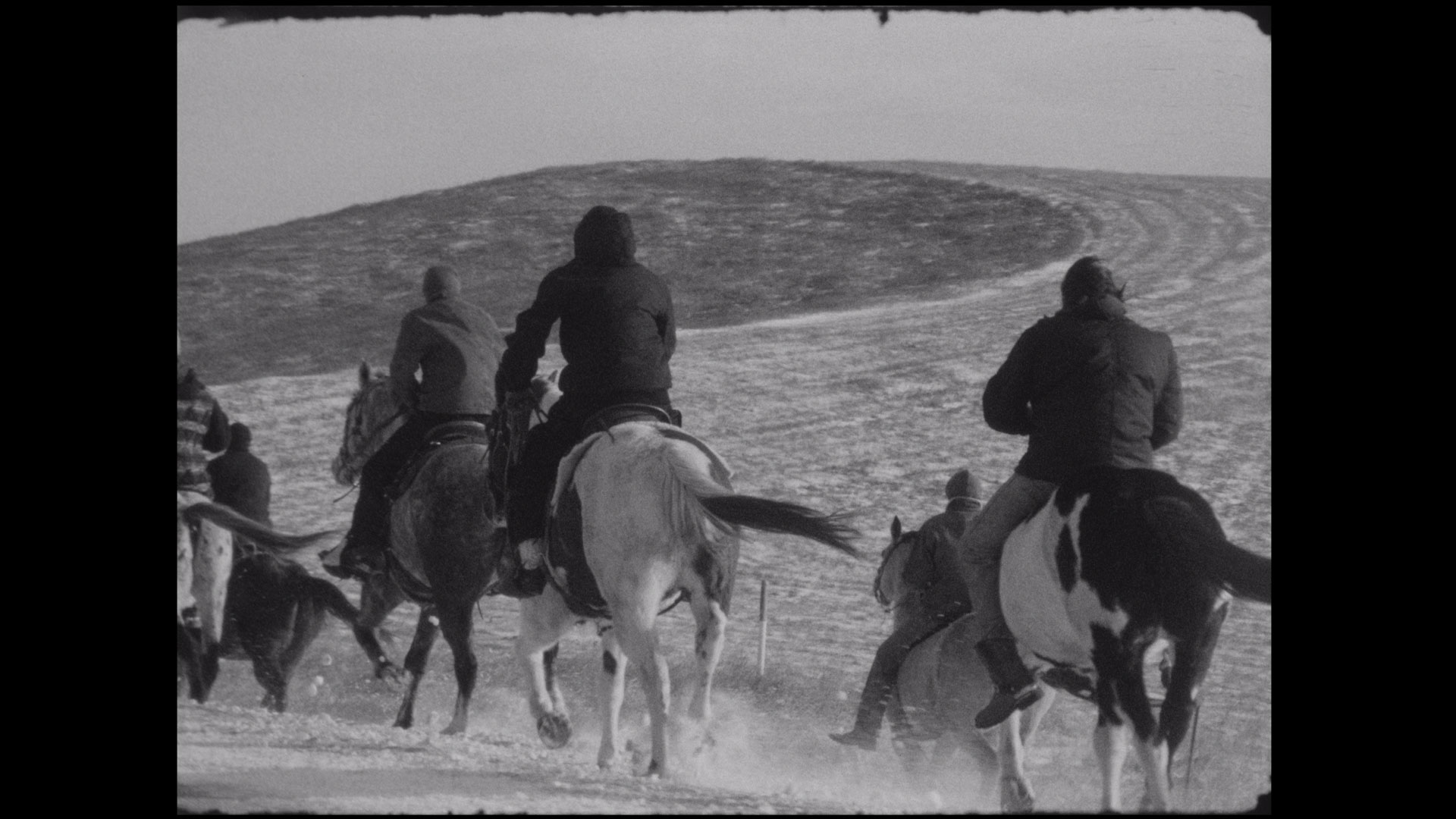

Karthik Pandian, Anoka (2025), frame enlargement. Courtesy of Film at Lincoln Center.

The concept of community takes on a broader, more global and historical context Karthik Pandian’s Anoka. Pandian plays voice-overs of various conversations he has with others surrounding words, phrases, and definitions from different cultures on top of visuals that progressively go from abstract to concrete. The sound design of the film is filled with chuckles and jovial voices in various languages – Spanish, K’iche’, Lakota, Ojibwe, Tamil, and Sanskrit – finding delight and surprise in the commonalities across languages as the film goes along. Pandian starts off with flickering and jittering images of what seems like a section of forest while he and a native K’iche’ speaker teach each other phrases and words in K’iche’ and Tamil. The film then shifts to conversations with members of the Lakota Nation where quick scenes from various ceremonies, community projects, and general lifestyle events are shown in a montage. Emphasizing the connective power of language, Pandian shows collaboration and learning among people on the reservation. One extended sequence shows three Lakota friends holding a long stick, which Pandian affixes his camera to. They try to balance the camera on the stick while pulling it towards them. In its intertwining of communication through words and actions, Anoka feels like a clarifying statement on global exchange of words and histories.

New Red Order (Adam Polys, Adam Khalil, and Zack Khalil), Give It Back: Crimes Against Reality (2025), frame enlargement. Courtesy of New Red Order.

First as tragedy, then finally as farce, the section rounds out with New Red Order’s Give It Back: Crimes Against Reality. New Red Order is a ‘public secret society’ (ha ha) founded by Adam Polys, Adam Khalil, and Zack Khalil, and their mission statement for a more equitable future of Indigenous folks is to “transcend shame and guilt… and imagine something through and beyond.” Crimes Against Reality embodies the energy of this, delivering a plea to its viewers as a “grand opportunity”, much like what a real estate agent or a finance guru might pitch you on– except here, it’s about giving up your house, your belongings, your occupational space to the Indigenous community it was stolen from over the past 200 years.

Featuring a “former Native American impersonator” Jim Fletcher, with added commentary by Libby Schaff, the former mayor of Oakland, and Christine Sleeter, a college professor, the movie switches between talking head documentary, a corporate commercial with CGI diagram effects, and a narrative of sorts starring Jim, who speaks to himself in several forms confronting what is means for a white man to give his property back and what capitalist traps inherently exist within the idea of “property” itself. What’s strange and fascinating about Crimes Against Reality is how the experimentation lies in the subtext moreso than the imagery. Forcing a fusion between mainstream commercial advertising and radical politics, the film is both ironic and sincere, and it doesn’t allow itself to be pinned down as one or the other. We are inundated with calls “to do better” and “make a difference,” but served with a side of tongue-in-cheek jargon like “operationalize your property to materialize the process”. Crimes Against Reality deftly confronts not only the American viewers’ propensity to be susceptible to certain forms of propaganda (namely, capitalist) over others and conditioned to listen to certain argumentation (corporatist) but shrewdly mimics and weaponizes them. The filmmakers make the bet that all of us, regardless of what part of the political or social spectrum we land on, are susceptible to this exact kind of advertising—that we are conditioned, by virtue of living in the United States, to think in the terms of corporate iconography and don’t recognize it as propaganda at all. The bet pays off.

Review by Soham Gadre

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.