War in Pieces Continued

Fernando Saldivia Yánez, Winter Portrait

(2024 | 16mm to HD | Color | 9 min)

Prismatic Ground Film Festival Year Five, Opening Night

April 30-May 4, 2025, various NYC venues

Winter Portrait documents a wedding in Traiguen, Chile. The ceremony is conducted in Mapudunguén, the disappearing indigenous language of the Mapuche people. On a flat screen in the center of the frame, a TV news report about the event is running. It is viewed by a man, possibly the filmmaker, and a woman, possibly the bride’s mother, who records the screen with her phone. The report includes statements by the bride (“It is a very beautiful language. It is ours and we are losing it.”) and the groom (“We want to set an example so that others are not ashamed of speaking their language,”) Then the news report is replaced by home movie style footage of cows, sheep and ducks, in the very pasture visible through the window behind the flat screen. This makes the background more significant than the ostensible main subject, especially after the two person audience exits the frame. One realizes that the video file could have been dubbed and shown directly. But the once-removed presentation, a story within a story, highlights our cultural distance from the event, giving the work a special sense of both intimacy and detachment.

adieu ugarit | وداعاً أوغاريت

Samy Benammar

(2024 | 16mm to HD | B&W | 15 min)

Prismatic Ground Film Festival Year Five, Opening Night

This film’s haunting effect is also dependent on an element irrelevant to its story content. The main character, a survivor of the Syrian civil war, is traumatized by his memory of a friend’s execution. Shadows of the past pervade the film, a tone evoked by a dissonance between the dark emotions of the subject and the calming qualities of the Laurentian Waters.

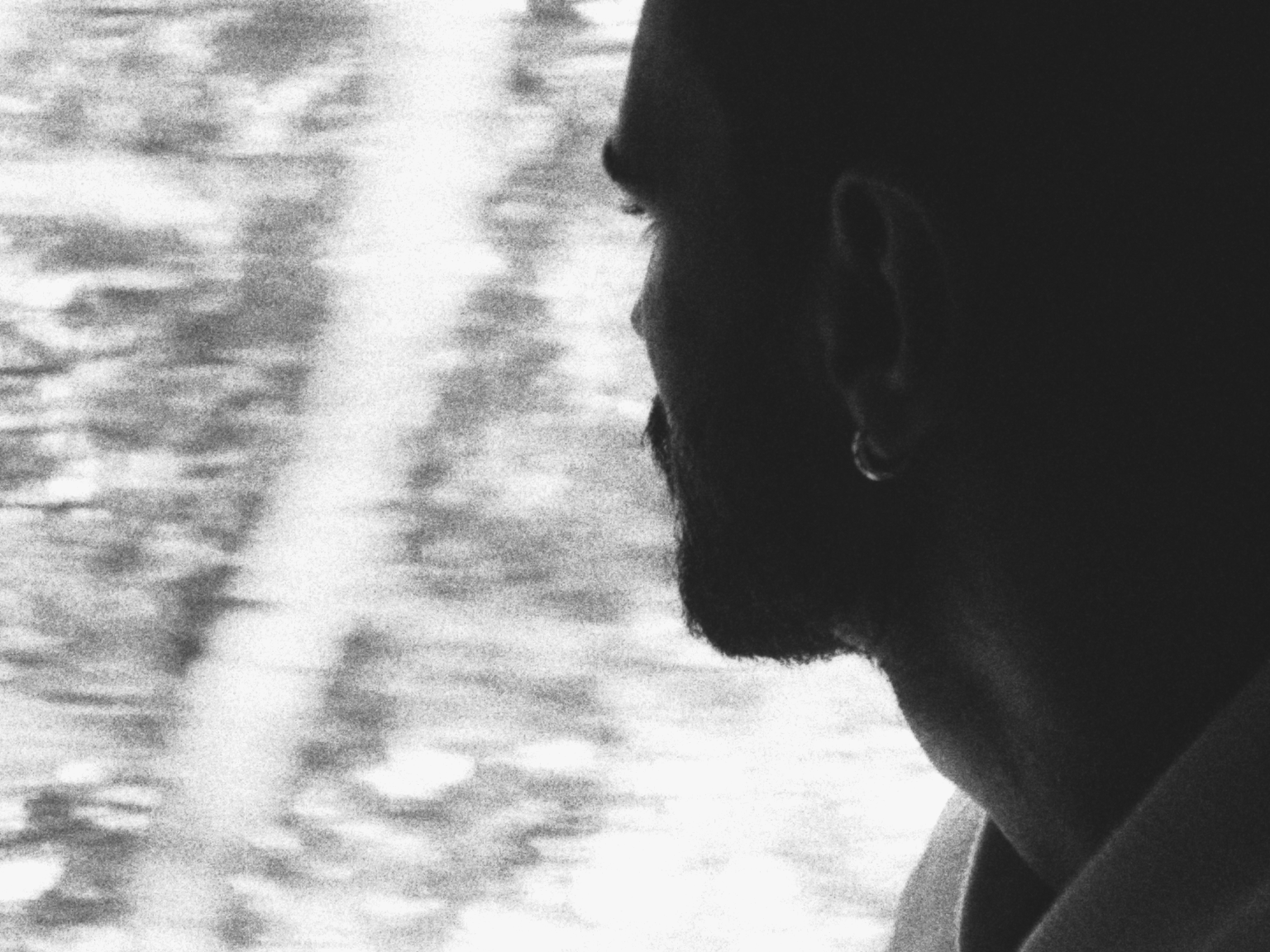

Mohamad Awad presents his story in an environment that radically contrasts with Damascus where the traumatic incident occurred. His reaction to the view of a placid body of water is in these words: “I run away from water. Its sound. Its shape. Its color. I can see only one thing: puddles of blood and half a body floating.” With this understated outpouring we are treated to a shot of a turtle-like rock, unsullied water lapping around it. Blemishes of light along the edge of the monochrome 16mm frame peppered with dust and scratches suggest an irrevocable, irreconcilable past. The handsome man stares into the water and we feel him projecting his memories onto its tranquil surface as he describes his fragmented visions.

Were we to mute the audio and the subtitles, adieu ugarit would read as a modest celebration of sylvan lake-country lovingly recorded in black and white and intercut with images of a fine-looking man—with no suggestion of an absent voice-over narrative. It is in the contrast between image and text that a bitter emotional tone conveys the horror of violent death in the mind of someone who can’t escape it. Among countless works describing the violences of the world we inhabit, the distinction of adieu ugarit is in the divergence between the spoken text and the idyllic environment..

Among Zhuang Zhou’s many virtues was his talent for drawing.

The king asked him to draw a crab. Zhuang Zhou said he would need five years and a villa with twelve servants.

After five years he had not yet begun the drawing.

“I need another five years,” he said. The king agreed.

When the tenth year was up, Zhuang Zhou took his brush and in an instant, with a single flourish, drew a crab, the most perfect crab anyone had ever seen.”

Italo Calvino “Quickness” from Six Memos for the Next Millennium

Imagine you missed the beginning of this perfect parable, picking it up only at the very last phrase. Would you still experience its perfection? And if you waited for it to repeat and caught the beginning on the next round?

If you come into CROSSROADS 8 minutes before the end? Or entered the screening of Being John Smith during the final scene? Will you catch the emotional power of the later scenes without the data gathered earlier?

The last scene of CROSSROADS is a sea-level view of one of the many anchored ships. The deadly cloud released by the atomic bomb detonation advances lazily toward the camera. One assumes it is not a threat—it must be that the vessel is anchored, and, we hope, unmanned, though there may be goats, mice, pigs, rats and sheep aboard as lab subjects to test the effects of the radiation generated. The ship disappears under the column of radioactive steam. For a period we watch the cloud shift and reform, a recovery time for the viewer after enduring multiple money-shot detonations. After the nine long minutes of semi-calm, the vessel emerges from the cloud, still whole, still upright, apparently undamaged. It is an emotional release, a deliberately extended last act for the most extreme horror film ever made.

Much is gained by gallery exhibitions of artists’ moving image works. But for a viewer entering the screening room during the final nine minutes of CROSSROADS much is lost. The concluding scene by itself means nothing at all … a punchline delivered without the joke. A vital element is potentially eliminated by the film’s continuous looping. As Ross Lipman writes in the insightful essay previously cited:

. . . the film’s last shot, which lingers over the seas for an extended time after the bomb’s blast, can be hinted at but not fully experienced with mere glimpses. In this way CROSSROADS is not unique: key aspects of many moving image works cannot be fully conveyed in the context of ambulatory, non-sequential gallery viewing.

Better would be to begin at announced times with breaks between. This small concession may help to preserve the painstakingly designed cinematic constructions and what is communicated through them … and demonstrate appropriate respect for the labor of artist filmmakers.

Article by Grahame Weinbren

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.