Thoughts on Shirley Clarke and The TP Videospace Troupe

This review by Andrew Gurian was originally published in the Millennium Film Journal issue no. 42 “Video: Vintage and Current” in 2004.

Shirley Clarke’s reputation as a filmmaker is as secure as anybody’s, and any history of film that omits her is lacking. Her work in video is as startling and creative as her work in film, yet she has been repeatedly overlooked in histories of the early video movement. She pioneered video installations (her “Video Ferris Wheel” at the 8th Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York, 1971, for example) and video technology (she designed, with Parry Teasdale, a wrist-watch camera by taking apart a portable camera and separating its components). But her most extraordinary use of video was not a performance, a tape or an installation, but her unique workshops. The workshops were live and evanescent events; what remains are fragments….

Midnight

1972 or 1973. A group of about 15 people have gathered inside the base of a pyramid, originally erected to support a flagpole on the roof of the Chelsea Hotel, on West 23rd Street in Manhattan.

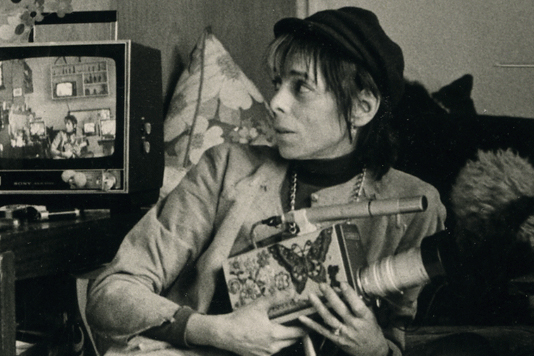

Some time ago the pyramid, a permanent structure, was divided into several spaces on several levels. It had windows, furniture, plumbing—and now a network of audio and video cables running to and from each interior and exterior space. It was also Shirley Clarke’s home/studio, and on this evening she introduced the group members to each other and to what lay ahead in an eight or nine hour video workshop: video game-playing, portrait painting, tape-making—all to culminate in a grand four-channel playback at dawn. Five feet tall and with the trim body of dancers half her age, Clarke always wore something on her head, and, favoring black and white, that something could be a small cap, Mickey Mouse ears, or a silk top hat.

The Totem

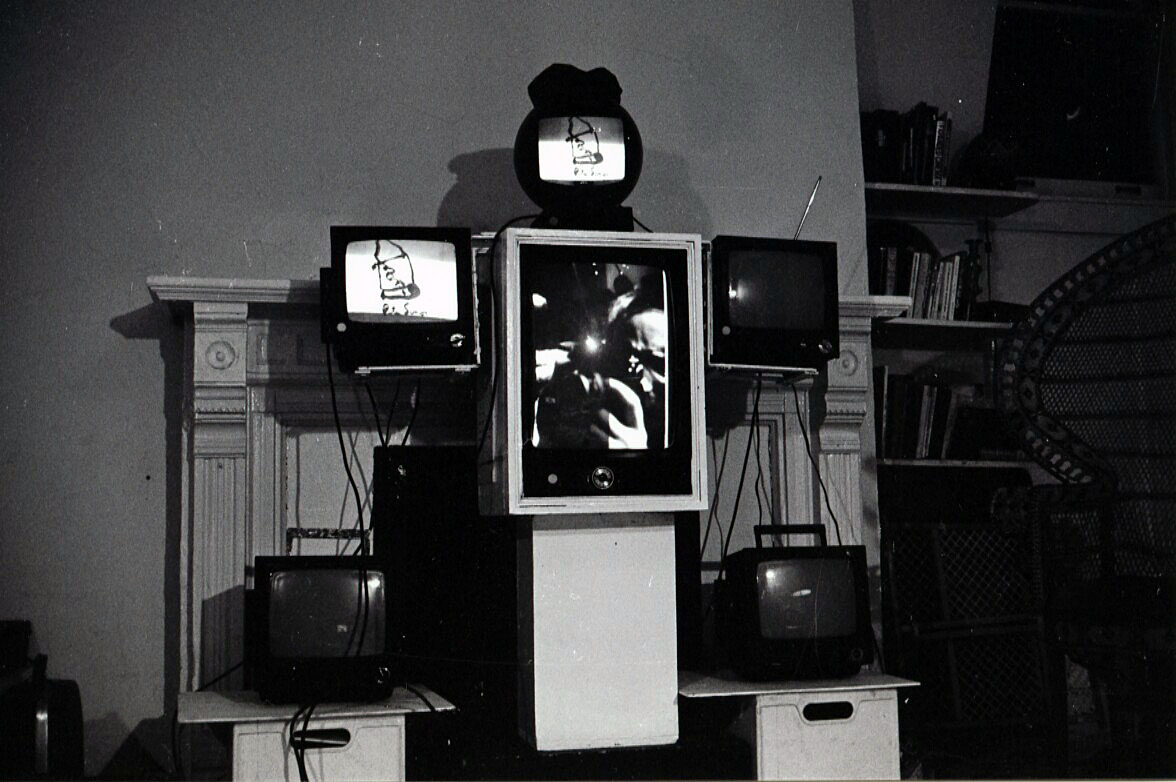

A top hat also crowned the Totem, now standing and facing the group. Clarke had built a human-like, totem-pole-like form using four b&w video monitors: a 19” monitor, rotated 90 degrees so that it was oriented vertically, was the torso; two 11” monitors were arms; and one small monitor with spherical casing was the head (the “ball”). Each of the four monitors could have a unique image, and the images could be live or from videotape.

Clarke constructed a bank of four cameras in front of one person, whose head, arms, torso, and legs became the source of the four (live) images. Next, four people contributed one body part each to create a new composite, and then live body parts were combined with recorded ones. Members of the workshop played with a variety of totem images; and whatever or whosever arms, legs, heads, and torsos were on screen, this Totem could dance in ways no human being could.

Then Clarke explained that the Totem facing the group was only one of many in her studio.k top hat.

The Beginning Discovery

In 1970 Clarke received a government grant, via a program sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art, with the understanding that the grant was to enable an established artist familiar with one medium to work in another. Clarke, a filmmaker, wanted to use the grant to invent a new protocol for editing film, by using video technology. She took the money and bought a studio-full of the just-developed Sony and Panasonic video hardware: cameras, Portapaks, edit decks, monitors. Immediately, she discovered the technical impossibility of her project—that of editing videotape. It should not even be attempted.

But Clarke discovered that video offered something new and exciting: live, moving images, which could be transmitted to several discrete architectural locations simultaneously.

Moreover, the images could travel in two (or more) directions: two people in different rooms, for example, could each carry a camera and two monitors so that each could see the other camera’s live image as well as a live image of the other person.

Video could dissolve the distinction between creator and audience; anyone could use a camera and create live moving images. The images were immediately available to be combined with other people’s images on adjacent or nearby monitor displays.

Video was not subject to complex editing: images existed in real time and were combined—not one after the other—but one with, or next to, the other.

Video asked to be made and seen inside an architectural/physical environment: combinations of monitors built up larger forms—not in a darkened theater where the spectator was the fourth wall—but as one part of larger space.

Video implied something beyond the frames (housings) of monitors: it acknowledged both what was inside and outside the border of the camera’s image.

Clarke created a workshop environment that could demonstrate these elements of video.

The TeePee

Clarke’s rooftop pyramid became The TeePee. The space tapered gently as it rose about 25 feet to its apex. The lowest interior level was a sunken living room/kitchen. Up a flight of stairs was another space, approximately 15’ X 20’. Above this, more stairs led to a small platform. Access to the building’s roof was from the lowest two levels; there was approximately 1500 square feet of private outdoor space. Across the roof, Clarke rented an additional large studio to live and work in.

Clarke wired each of these spaces for video and audio. A custom-made, portable matrix switcher (patchboard) sent and received signals between spaces, each of which was also equipped with a variety of monitors and cameras. The switcher enabled transmitting an image originating in one space to all the others, and vice versa. And the electronics was always fired up. TeePee regulars co-existed with random, live video images of themselves, the floor, the windows, furniture, Clarke’s poodles, video monitors, even broadcast television.

The four spaces (lowest level, second level, high platform, outdoor roof) were usually nicknamed colors (red, blue, green, yellow), occasionally geographical places (Paris, Tokyo, New York, for example). All this was a model for the anticipated inevitable: the ability to send and receive simultaneous audio and video signals to and from anywhere on earth.

Sometime in 1971 Clarke conceived of a group of artists, drawn from the full compass of disciplines, who would develop new skills for a new art. She appropriated the model of the jazz ensemble: videographers would improvise, trading images back and forth. Clarke’s reputation and contacts attracted such people as Arthur C. Clarke (no relation) and Peter Brook; actors Jean-Paul Léaud, Carl Lee, and Viva (a close friend who lived across the hall); filmmakers Richard Leacock, Nicholas Ray, Willard Van Dyke, Peter Bogdonovich, Milos Forman, Agnès Varda, Harry Smith, Paul Morrisey, Michel Auder, Severn Darden, Storm De Hirsch, and Lech Kowalsk; Zen writer Alan Watts; poets Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg, and Peter Orlovsky; jazz giant Ornette Coleman; and notorious cable-TV pioneer Irving Kahn. The video world was represented by Nam June Paik, Shigeko Kubota, the Vasulkas, Shalom Gorewitz, Ira Schneider, Philip Perlman, and lots of others. More regular were TeePee members Wendy Clarke (Shirley’s daughter), Bruce Ferguson, Shridhar Bapat, Susan Milano, Elsa Morse, DeeDee Halleck; and VideoFreex commune members Nancy Cain, David Cort, Davidson Gigliotti and Parry Teasdale. The TeePee became a salon as Clarke sought to incorporate the range of talents of its visitors.

From an interview with Clarke in Radical Software:

Dancers spend years training their bodies and developing the technical skills necessary to dance—and it’s the same for musicians, for actors—whatever new media you choose, it’s the same story. But what are the skills needed in video that humankind never needed before? Well, one unique capability of video is that we are able to put many different images from many different camera and playback sources into many different places and into many separate spaces (monitors) and we can see what we are doing as we are doing it. We need to develop better motor connections among our eyes and our hands and bodies—we need balance and control to move our images from monitor to monitor or pass our camera to someone else. But mainly we need the skill to see our own images in our own monitors and at the same time see what everyone else is doing. We need to acquire the ability to see in much the same way that a jazz musician can hear what he is playing and at the same time hear what the other musicians are doing and together they make music.1“Shirley Clarke: an interview,” Radical Software (New York: Gordon and Breach, Science Publishers, Inc.; Vol. II, No. 4, 1973) p. 27.

Over the next five years this group—The TP Videospace Troupe—gave workshops at the TeePee and toured in the Northeast. Membership constantly changed and at any given time was between four and ten people. I joined in 1972, soon after I graduated college. My artistic career had begun when I started making movies at age 12, in 1962. I continued making films as a teenager, some with Rodger Larson, who, at the Mosholu-Montefiore Community Center (Bronx, NY), the 92nd Street YMHA, and the Film Club of the Young Filmmaker’s Foundation, was among the first to put 16mm cameras in the hands of teens. These films caught the eye of Willard Van Dyke, who gave me Clarke’s phone number and told me she was “doing interesting things with video.”

1:00 AM: Playing Games

At the workshop there were two identical Totems (four monitors each), one in each of two of the TeePee spaces. The group split: one half remained downstairs and the other half went upstairs. One person from each group stood in each space, facing the Totem. A camera in, say, the red space fed an image of the “red ” person’s head into the “head” ball monitors; another fed her right arm into the right “arm” monitors. From the, say, blue space a camera fed the “blue” person’s left arm into the left “arm” monitors and another fed the “blue” person’s torso and legs into the large, vertical “torso” monitors. Everyone saw the same four-channel image—the red head and red right arm and the blue torso and blue left arm. The blue person and the red person created a new, conflated Totem; with it they could play “Head-Body Games.” People wiggled their arms and legs together, tried to clap their hands, and danced.

Video painting, developed by Clarke’s daughter, Wendy, was next. The painter took brush to paper but looked only at the subject (usually a person) or at a monitor. A camera focused on the paper at a severe angle, such that it transmitted a foreshortened image to the monitor. The painter’s work was to draw a realistic portrait for the monitor display, while “correcting” the distorted proportions created by the camera’s angle. The painter did not align his eyes and head with his arm and brush in a traditional posture. He might be literally painting behind his back. He was testing new skills of connecting his perceptions to his actions. The paper version usually had exaggerated lengthening, especially in comparison to the version on the monitor. After the initial drawing was made, translucent paper was sometimes placed over the monitor display and ink tracings of the portraits were made. These tracings, still in place on the monitor screen, were fed through a camera to another monitor and layer upon layer was built up. The paintings existed on the monitor and on the paper; either or both could be evanescent, but some were saved (on paper, videotape, or both) for playback later.

In another configuration, the painter stood. He made a self-portrait, watching his video image in front of him. A pad of paper hung from his neck like an apron and he painted on his stomach, watching the result on a second monitor, a few feet in front of him.

In the early 70s most of us did not yet possess the technology to venture forth on electronic crossings over vast distances in space; we could only play at it. Much of the workshop material—real and virtual (images on monitors)—was childlike, game-like. The TeePee was stocked with costumes, toy musical instruments, masks, and arts-and-crafts supplies. During the “Head-Body Games” Clarke encouraged people to use this inventory, more suggestive of a kindergarten than a sophisticated New York artist’s studio. She humanized the machinery: monitor housings were painted and cameras were decorated with cutouts and decals (many were of Clarke’s beloved Felix the Cat—she claimed his was the first image ever broadcast). Control knobs were camouflaged. This gear was to be disentangled from its imposing super-tech look. Its origin of manufacture by big, big industry was to be negated. The vernacular was to replace all tech talk. (Clarke found, however, she could not avoid jargon with equipment dealers and engineers. She conceded defeat in this part of the battle against domination by the technology; she vowed if she were ever to re-marry, the groom would be a TV repairman.) Our hammers and screwdrivers were enameled milky-pink (in part so we could distinguish them when on tour), making them, too, look like toys. Indeed, The TeePee was also called The TP-Tower Playpen. Many work shoppers resisted this return to juvenile childhood, but the rewards were high for those who fell under the spell.

I hesitate to psychoanalyze or over-interpret Clarke’s concentration on childhood or the childlike. But she did make some film shorts featuring children (“In Paris Parks” and “Scary Time”), which were curious in light of her better-known films, Portrait of Jason and The Connection.

Some critics complained that these “Head-Body Games” had only simplistic content. The games in and of themselves were ultimately of little consequence, and the “new-age” references to totems, magic, mystic power, and shamanism seemed trivial at first, even condescending. Clarke would agree—and disagree. She said that her contribution was to suggest possibilities (her word) and paradigms, leaving them for others to perfect, that more significant content was to come later. (Some other observers, though, were probably not interested in content of any kind.)

But this from Jonas Mekas:

In truth, nobody had a good time. Many simply got bored and left, including Shirley’s mother. You see, everybody expected something profound, or new, or carefully orchestrated to happen….So everybody was disappointed. Because nothing happened, nothing serious happened. One thing happened, however: by the end of the evening, those who remained finally understood that what Shirley was telling them was that video is just a toy. So they began playing with it. That is, they retreated, as well as they could, back into childhood days, and they began playing with cameras, and everybody goofed and had a good time, including me.2Jonas Mekas, “Movie Journal,” The Village Voice (New York: May 20, 1971) p 63. Mekas was writing about a Clarke retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, to which she had transported a truckload of video equipment from home.

And this from Clarke:

We need very much as adults to play. To understand that playing is art and art is playing—what is the difference? We’ve separated these things much too long. We’ve lost the tribal culture and we’ve lost shamans and the campfire and the group energy that’s needed if the rain dance is to produce rain. We have separated the artist from the group. We’ve gotten to the point now where there are these freaky people called artists and then there’s everybody else—we are changing that, and video is the tool that will let the artists connect back, by interacting with the group—that is, if we can learn how to use video properly.3Radical Software, p. 27.

Also consider,

The Totem Tapes

Many early investigators used video to turn the camera back on themselves or to encourage the viewer to become the subject, but Clarke’s contribution to this schema was the most intense. She asked people to enter a private architectural space—their own bedrooms, an area in the TP, for example—and set up a small monitor fed by a camera situated just a few inches above it. The subject/tapemaker faced the monitor and looked directly at the live image of her/his head. A tape recorded the subject’s looking, commenting, face-making, doing nothing—whatever—until the tape expired thirty minutes later. (Thirty minutes became a standard duration in much tape making at the TP. Sony designed the Portapak to hold a thirty-minute reel; it was convenient to make a tape until it simply ran out. It became as natural to measure time by the reel as by cycles in nature.) No other subject matter or instructions were suggested. She called the resulting tapes “Totem Tapes.”

For some, the exercise was empty or routine. For others, it was emotionally profound—to the point that Clarke was sometimes concerned about possibly dangerous psychological consequences. But, for everyone, this modality introduced the concept of seeing and making a live, moving image that could also be saved. It demonstrated the concept of public/private space/time and who might or could control images. In my own first Totem Tape, I made a “mistake.” I stared at myself, made funny noises and faces, thought about this and that. Only then—about fifteen minutes later—did I push the record button. Afterward, Clarke told me I missed the most important fifteen minutes.

Video’s seeming ability to let anyone turn inward and glimpse at the true soul was undeniably appetizing for early experimenters. It would, after all, be a pity to deny such a powerful tool. Everyone—artists, critics, philosophers, semioticians, psychotherapists, aestheticians—sideswiped each other racing to define it, analyze it, and practice it.

For example, video artist Paul Ryan:

When you see yourself on tape, you see the image you are presenting to the world. When you see yourself watching yourself on tape, you are seeing your real self, your “inside.4Quoted in Jud Yalkut, a review of the 1969 Howard Wise Gallery show “TV as a Creative Medium,” Arts Magazine, September-October, 1969) p. 20.

Plenty of other artists of the 70s made tapes or installations in which they looked directly into their own image. But it is important to remember that most of these works were made by artists to be (passively) viewed by other people (an audience). When the viewer or audience also becomes the subject, we quickly get the point of the other as ourselves, of what Rosalind Krauss calls “reflection vs. reflexiveness.”5“Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” October Spring 1976, pp.51-64. These works did often demonstrate video’s potential to slip the viewer from architectural space to video space, but watching most people enter these variations on video feedback loops was not unlike watching people today playing with their own images in the windows of electronics stores in shopping malls.6I refer to Krauss because of the wide attention her article has received; she mentions such works as Peter Campus’s mem and dor. Less circulated is Allan Kaprow’s “Video Art: Old Wine, New Bottle” (Artforum, June, 1974). He refers to the same or similar works as Krauss; however, Kaprow adds it all up and finds it “intriguing” but also “discouraging” and “quite tame,” “simple-minded and sentimental.” Jeff Perrone, while praising three 1976 Campus installations, still comments “[m]ost of the time I was in the gallery there were people making monkey and hyena noises.” Perrone also quotes Roberta Smith’s observation that “’Campus limits access to the image; it is vague and unresponsive, psychologically distant.’” (“The Ins and Outs of Video,” Artforum, June, 1976 p56)

The Totem Tapes asked for more. Subjects understood from the outset that thirty minutes was to be the duration of the event, and this length demanded some commitment. The tapes were private. Anyone could erase her/his tape before anyone else saw it—though few did.7Another Kaprow complaint was that public art galleries are not conducive to serious inward meditation or meaningful communication with another person, contrary to what many video artists request or assume. “Everyone is on display as a work of art the minute they enter a gallery. One cannot be alone. A gallery is not a retreat.” (Artforum) Perrone notes the gallery can become a “sterile living room.”(op. cit., p 54)

The making of Totem Tapes was primarily a process in, of, and for itself. They were not intended to mimic or reference any particular theory of psychology—such as Krauss’s analysis of Freudian and Lacanian narcissism—though they were not intended not to do so. For most people, they were “memories, dreams, reflections” and—in Krauss’s phrase—moments of “reflexiveness.” For others, there was also narcissism; for some, fear of narcissism; exhibitionism and fear of exhibitionism; revealing secrets and keeping secrets.

Most of the Totem Tapes retired to boxes on a shelf. From time to time, somebody showed his to a friend. I once had occasion to watch four or five simultaneously, each on its own monitor. In this playback context, they fascinated. They conveyed an atmosphere of focused concentration on an unrevealed common cause or purpose—directness, humor, chance, and anything else you would care to impose on them or extract from them.

We at the TP were continually watching images of ourselves because our equipment was always turned on. I decided after a few weeks at the TP that I had better find a way to do so without the queasiness I initially felt. I have always believed that most people feel awkward about their own appearances, and seeing themselves on video calls their attention to their uneasiness. I developed a skill whereby I could invoke a different persona for myself. I trained myself over time to see my video image not as me but as someone else. Only this way could I be objective about my appearance. I became an average guy, just like anyone else—not perfect but good enough. To see yourself with this learned, un-spontaneous, self-conscious objectivity is probably the most accurate way of seeing yourself (maybe what Ryan meant by “your real self, your ‘inside,’”—but maybe he meant the opposite), and it is probably the closest to how others see you.

Perhaps Clarke called them “Totem” Tapes because, like the other video totem formats, they spoke to the same issues of magic/image/power/group/ individual. Totem Tapes were not visual recitations of people with blank expressions staring at cameras. They were a new kind of portrait with continuous input and output from the subject. To make a Totem Tape was to experience the video rite of passage. Nowadays, anyone can make one at home.

Just maybe the Totem, the Totem Tapes, and the video games did have considerable and worthwhile content. Shirley was the shaman, electrons were the power, and the magic was to come at dawn.

2:00 A.M.: Making Tapes or “I’ve never seen a videotape I liked”

The workshop split again, this time into four groups. Each section, led by a TP member, completed its own half-hour tape, with simple editing in the camera. Some groups moved to different spaces in the TP, some ventured to farther locations in other parts of the city. Sometimes, people went back to their homes to make tapes. Each section worked independently. The first ten minutes or so of each group’s tape already had images from the Head-Body games and video painting.

Most workshops had themes to which most groups attempted to be true. One workshop featured a party theme for the joint birthdays of Clarke and three of her favorites: Groucho Marx, Mahatma Ghandi, and her very own Max the French poodle. Clarke titled the event, “Happy Videobration.” Refreshments included a pot of chili and birthday cake. In another, three-day workshop, for a video group of the Women’s Interart Center, eight women, all wearing masks and some carrying ball monitors, joined a Sun Ra concert onstage at Town Hall in order to record images for playback later. Themes for a workshop at Antioch College (Baltimore) were life cycles (birth, adolescence, adulthood, death) and the elements (fire, water, air, earth).

Here we were at 2:00 A.M.; Clarke had us making tapes.

But whenever Clarke was asked if she liked this or that videotape by so-and-so, the response was, “I’ve never seen a videotape I’ve liked.”

Tee Pee Video Space Troupe: Feb 23, 1971

Tee Pee Video Space Troupe: Yoko's Trip, tape one

Thousands of fragments of the Tee Pee Video Space Troupe can be found in the archives of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research.

Filmmakers and Filmmaking

Clarke began her artistic life as a dancer. The subject of her first film—Dance in the Sun (1953)—was a dance. Many short films later, her subject matter was still dance—and that which dance and film had in common: motion. But film had a movement all its own and a tempo all its own, determined by editing.

About fifteen years after Dance in the Sun, in the late 1960s, portable and inexpensive video cameras and recorders became a reality. This technology followed the invention of professional, portable, sync-sound motion picture equipment by about a decade and a half. Videotape was cheap; 16mm film was dear (dearer still for the costs of developing and printing). But film was cheap to edit (you needed a viewer, a pair of scissors, and tape or glue). Editing videotape on the other hand was either expensive or, in the case of small-format video, expensive and lousy.

And so early independent videotape makers inaugurated an era of long and boring “electronic films.” Tape was so cheap that it quenched any thought of letting go of the record button, and the frustrating technical problems of editing undermined any inspiration of tightening the work. The film editors’ slogan, “when in doubt, cut,” became the videotape makers’ slog, “when in doubt, don’t assemble a sloppy edit.” Editing, the beating heart of filmmaking, became the clogged artery of video.

Many believed in the promise of the early 1970s, the promise to liberate the moving image from the monopoly held by mass-media moguls and their enormous corporations. Hollywood studios and network television could now be challenged by local grass-roots groups. Downtown Community TV, Paper Tiger Television, Raindance, Videofreex—all tried to bring the power of media to the people. And, indeed, there was some success.8For a history of this movement, see DeeDee Halleck’s Hand-Held Visions (New York: Fordham University Press, 2002) and various numbers of Radical Software, now available on-line. The notion that video was somehow to make art more “democratic” has been repeated often enough.9For example, Bruce Kurtz, who uses the word in “Artists’ Video at the Crossroads,” Art in America (January 1977), and Jeff Perrone (op. cit. p.53), write that they are only passing along what many before them have said. It was certainly a concept Clarke espoused.

Just as Krauss found narcissism intrinsic to video, many people consider progressive politics a video built-in. Michael Rush, in 2002, makes much of early video’s unusual acceptance of a large number of women.10See his “No Longer an Orphan, Video Art Gives Itself a Party,” The New York Times, February 10, 2002 Section 2, p. 35. (He mentions eight, but misses Clarke!) The attraction to video felt by the relatively disenfranchised is best understood in the context of the traditional economics of filmmaking and the society of filmmakers. (Elitist skeptics will reply that all video has done is to give cameras to the masses, and now we must suffer what the masses give us back.) It is obvious that forms such as painting or poetry, though historically laden with political and social elites, do not face the same financial issues as film does because their means of production are so inexpensive.

One branch of the new video practitioners experimented with “electronic painting”: making abstractions and non-objective designs. Synthesizers, chroma-keying, and feedback were the engines driving these tapes, by such makers as the Vasulkas and the Etras.

Some video artists (and critics) emerged from the world of fine arts. They were often oblivious to the video output from the filmmaking community; their focus was on whatever could be exhibited in an art gallery. Thus, Perrone’s startling comment, “almost all…video artists…work or worked with visual material in painting and sculpture.” (Artforum) Fine-arts-based criticism tries to differentiate between videotape as documenting some other art, usually a performance, and videotape as an artwork in its own right.

For Clarke, this was simply filmmaking or picture making on the cheap. Her filmmaker’s eye saw videotape-qua-film as undisciplined, bad-looking, and bad-sounding, with edits that further destabilized the already crippled image—all on a small screen of washed-out gray murk. It hardly mattered whether the maker was from the world of film, the plastic arts, music, or literature.

Video was fighting for its own aesthetic identity, and most tapemaking was not helping. Video’s chroma-keying imitates film’s blue-screen and traveling-matte processes; other video special effects imitate film’s optical-printing possibilities. Zooms, close-ups, dolly shots, and panning are all inventions of film. The history of forcing the capabilities of video editing is the history of spending millions of dollars and building mountains of black boxes with their secret inner organs, only to imitate a razor blade, tape, and glue.

To be fair, Clarke did retreat from her anti-tape dogma from time to time. She was a lifelong believer in progressive political causes (including feminism), one of which was to challenge the control of mass media. In this she echoed and valued the contributions of those who took on the big guys by experimenting with tapemaking in small formats. I do not think I am extrapolating too much to say that Clarke recognized that low budget, lo-tech tapes were not necessarily ends in themselves but part of something larger. They indicated a change in the control of the image. That was important in the 1970s—and it is even more so today. Aesthetic principles of video would develop.

Clarke realized that, in her words, “broadcast television is just a method of film distribution.” Most broadcast TV was made of movie-like images routed to the living room and did not exploit the potentials of video. (But when it did, it was exciting. TV could distribute a live news event on a global scale. It was when Clarke passed a store window and saw a television tuned to a live feed of the McCarthy hearings that she considered the merits of owning one of these boxes.) Whatever alternative value small-format videotapes offered, to be effective they required a new means of distribution. Clarke once wrote a long description of how to create such a distribution system. In essence, short tapes would be created at a local level and shuttled to central hubs (community centers, museums, libraries) for immediate dissemination. (Clarke was also one of the founders of the Filmmakers’ Co-op.) In anticipation of the future technology of electronic conveyance, bicycles would do! She even planned the “First Inter-Arts Synergetic-Space Telethon” for October, 2, 1972, which was to use this system together with the resources of the local cable-TV company for a forty-eight-hour marathon to produce ten new videotapes. The tapes were to be a collaborative effort between two-hundred artists at the TP and the public. It was, however, too ambitious for the time and was aborted a week before the scheduled start date. No one can know for sure what these tapes might have looked like, but I cannot imagine they would have been extensively edited or have reflected professional production values.

Unlike films, the tapes made in the TP workshops had no start or finish; i.e., there was no frame around their time dimension. The long strip of magnetic tape coiled on a reel was a blank slate: as on a schoolteacher’s blackboard, the inscribed images were laid down, not at random, but without a sense of any field demarcated by a start or finish. The tapes did not gently fade in or fade out. At their heads the first images crudely burned into the video snow. At their tails they simply ran out and that was that. The frame around the two dimensions of height and width was also nebulous. It was determined by the shape, proportion, and orientation of the monitor screen, but simultaneously was destroyed by the monitor’s existing in an equally-felt architectural space.

The tapes unquestionably existed in a time dimension, as do films. But TP tapes were not conceived in shot-by-shot linear progressions. They were designed to be watched side-by-side with other tapes. Like films, they were played on a screen, but TP video screens were never in a darkened room or removed from exterior contexts.

I’m a good editor but I’ve stayed away from that in video because I’m not sure that’s what it’s about. I see the ‘video edit’ as a way of using instantaneous replay to make another tape. It’s editing in the sense that it’s after the fact of that moment. Tapes don’t have a beginning or an end. They’re so constructed in relationship to one another that they always synchronize. These ‘synch points’ are connections—no matter what gets fed in. They grow and change. They get erased. In video you use the monitor with the camera—they feed off each other. I call this “enfolding.” In film, you use the camera to get something on the screen.11Quoted in an interview by Susan Rice, “Shirley Clarke: Image and Images,” Take One, Feb. 7, 1972 p 22.

DAWN: Watching Tapes, Watching the Sun Rise

Just before dawn the entire group reassembled and the tapes played back simultaneously on a mosaic of eight or nine monitors of all sizes. This mosaic was a variation of the basic Totem construction.

Dawn arrived during the thirty-minute playback while the group ate breakfast.

What did this playback look like?—a free-for-all; a mumbo-jumbo of lo-resolution images (often out of focus). (See Clarke’s written comments on the “Playback of the Oct. 2nd Videobration” tapes, figure ??: “The fuck up.” This observation, repeated here three times, was not an uncommon one about TP tapes.) But the workshop playback was always successful, for two reasons. The first was to be found in what it was that the group watched.

Yes, the random juxtapositions of images assumed “meaning,” often loosely based on that particular night’s theme. But first came a few minutes of replays of the Head-Body games and video painting from beginning of the workshop. The rest, about twenty or twenty-five minutes, was what each splinter group had created by itself—and here surprises abounded, for each group’s tape was made apart from the other groups.

Over time, each TP member developed a personal style, which inevitably influenced his or her group. Clarke’s groups, for example, tended to produce Baroque-looking tapes (confusing, highly textured, distorted, complex, difficult to discern), and I often steered my groups in the direction of making “drone” tapes—tapes in which simple images held the screen for long periods of time. I knew these would counterbalance Clarke’s. One such tape featured only five or six separate shots, each one depicting some of the group crawling closer and closer toward the camera, for twenty minutes. These drone tapes “supported” a “sideground,” next to which other, more intricate tapes could comfortably fit and helped dilute a dizzying confusion the mosaic could impose.

Sometimes the images managed to go beyond the lo-res gray murk for which the early small-format video was famous. Some workshops even included an exercise whose sole aim was to produce an interesting looking and appealing or startling image. Occasionally, the video screen demonstrated what Barbara London (in describing a work by Bill Viola) called the “jewel-like luminosity” of the light-emitting CRT.

If these screen images had effect or meaning, the mosaic-sculpture of monitors surprisingly did too. The monitors were constantly calling attention to themselves. They consisted, after all, not only of an image-screen but also of a box-body. They had been decorated or personalized. Most workshop participants had occasion to lift or carry one, wire one, or in some way touch one. From the opening moments of the workshop, monitor-boxes had been used as a visual metaphor for the human body. The ball monitors had normal 4:3 rectangular screens, but because their housings were round, they could be perceived as spheres or heads. Clarke even once scripted a fifteen-minute dramatic piece anachronistically titled “A Radio Drama for Two T.V. Balls”; each ball was a character in a dramatic scene or dialogue. The balls were suspended by wires so they could travel up and down, swing, and rest on the ground. Their video images included faces, camera feedback, or written text. Live actors occasionally interacted with the image-monitor characters (who wound up dead and displaying their written epitaphs at the end).

The sculpture-mosaic added another “dimension” to video space. The workshop continually differentiated between architectural space (of a room, of the TP, of the city, of the world) and the video space of the two-dimensional, gray video raster. But there was also a new space of the monitor boxes, between monitor boxes, around them, behind them. Because the boxes related to each other spatially, their respective video images related to each other. And because their video images related to each other, the monitor-boxes related to each other.

The other reason for the success of the playback was the principle of process. During the prior five or six hours, participants discovered something about video space and video time. What that something was often depended upon who the participants were. Most were from an art background, but different art backgrounds.

Filmmakers, for example, discovered how time in video was different from time in film. Editing was imprecise, accomplished in the camera and on-the-fly. Shots were of long duration, with only minimal planning or rehearsal. You could see what you were getting as you got it. Light and contrast were difficult to control. For many, these qualities were frustrating; for others, they were liberating.

Painters and photographers instinctively pointed the camera behind their heads. Dancers felt a constriction by having to keep their eyes focused on a monitor, limiting some movement, but also inspiring a fundamentally new movement vocabulary.

During the playback these discoveries were on people’s minds. The dynamic of each group—how it decided what images to include, how it delegated different tapemaking jobs, how people interacted on a personal basis, what it thought about what other groups were doing—became conscious. The tapes in playback recalled a recently experienced past, but now in a new present, connected to another group’s recently experienced past. The joy of watching was intimately tied to the joy of making. The product of the playback, i.e., the images and their interplay, was incidental. A passive spectator, arriving only at the end of the workshop, might enjoy watching, but this was not the intention of these workshops. They were engaged in true “process” art; the experience had to be active, the tapes were mere relics.

Clarke recognized video as, “theater/experience. This has to do with the interchange between people and comes somewhat closer to therapy. And that’s art too because it can make you feel better….Video for me is the closest I’ve gotten to feeling as good as I felt when I was a dancer. This immediate response, the live thing. You see it, you feel it. You don’t have that terribly complicated time-gap of film.”12Take One, p. 22.

And the content? In the end, it was not so simplistic. Behind the childish magic was the mature magic. The tapes we made could never stand alone and lacked professional or technical finesse—but they did, as Clarke would say, make the sun rise.

Here was Clarke at her most radical: The TP workshops were ideal in pointing to art as active, not passive. Gone is the artist who creates a thing for a viewer, a reader, or a listener. This notion was sometimes threatening—downright scary—to career artists and other professionals in the arts industry (curators, funders, patrons, government administrators). I certainly felt unsettled. Anyone could be an artist; criticism, judgment, perfection, and elitism all took a back seat. Art ceased to be a fetish for the art object.

“[T]he mirror-reflection of absolute feedback is a process of bracketing out the object. This is why it seems inappropriate to speak of a physical medium in relation to video. For the object (the electronic equipment and its capabilities) has become merely an appurtenance. And instead, video’s real medium is a psychological situation, the very terms of which are to withdraw attention from an external object—an Other—and invest it in the Self.”13Krauss, op. cit.

Krauss, here, is building a bridge between certain video works that depict or use feedback loops and the Freudian “condition of narcissism.” Such works may or may not be of lasting interest, but she does touch upon something she holds in common with Clarke. For Clarke, too, the electronic equipment was an appurtenance. Keep in mind that in the early 1970s small-format video had severe limitations. The equipment refused to operate in accordance with the promise of the manufacturers. It was frustrating and difficult to achieve a variety of images that could compete for attention with other image-making media (film, oil paint, etc.). This is not to say it could not be done, but it was not the direction for which the medium of video was primarily suited. Pleasing imagery had to be secondary. What all these electronic “appurtenances” did, however, was something more than create an object of art. Let’s de-psychologize Krauss’s video from her words:

Video’s real medium is a psychological situation, the very terms of which are to withdraw attention from an external object—an Other—and invest it in the Self.

and aestheticize it to:

Video’s real medium is a situation, the very terms of which are to withdraw attention from an object of art—a Thing—and invest it in a process.

Clarke herself thought her video work was “process art.” Here’s a term that has been flung about—usually in self-contradictory contexts. A sculptor who throws molten lead against a wall may claim that what is important is the throwing—not the thrown or the thrower. But he has created an object, and it is this object that he sells. It is this object that is admired and it is this object that is displayed. True, the object suggests a process; but then Impressionism, too, suggests a process—painting en plein air. The Sistine Chapel ceiling suggests back pain and frescoes must be produced according to a strict procedure, but no one calls Impressionist paintings or Michelangelo’s works process art.

For Clarke, if you had a process you probably could not have a product. The art disappeared; it left no serious artifacts; it could only be replicated approximately. She never saw a tape she liked. Video was the ideal medium to demonstrate art as process precisely because the products of video, i.e., videotapes, looked so bad.

The inchoate, but nevertheless perspicacious thoughts of Mekas continue:

Shirley proved, or rather re-confirmed Nam June Paik’s old theory, that tv works best when all ‘image’ and ‘content’ is destroyed, when the sets are liberated for their own free, foolish, and useless existence. She further proved that tv, being a home medium, works best when it’s run by children fooling around with the cameras, having a good time….That’s what I was thinking last night.

This morning, however, I progressed along the following lines….I see Shirley’s show not as an attempt to give us an evening of information on those 12 or 13 tv sets she had; I see it more as ritual during which, metaphorically or ritualistically, she attempted (even if it was without her own knowledge) to liberate this new tool called video, to throw it into everybody’s lap, to do with it whatever one feels like doing with it. It means the possibilities of moving image making are still opening, the monopolies and dictatorships of moving image making are splitting still wider and wider open. The liberation of cinema is still continuing.”14Mekas, op. cit., pp. 63, 72.

Mekas then unfortunately strays from his point, which he himself seems unable to fully appreciate. He still insists on the model of one image-one monitor and evokes Richard Leacock as the “true prophet.” He is “down to earth” and “the glory of video…will be revealed…when the…video workers go into life and begin to record people, even if it be their own lives—people, and they will do it straight and clear.”

I recently watched Shigeko Kubota’s videotape My Father (1973-75). An opening title reads “My father died the day I bought an airplane ticket to go to see him. I called Shirley Clarke. She asked me how I was. I told her I was crying. She said, ‘Why don’t you make a videotape of yourself crying.’” Kubota did. My Father is an uncomplicated tape. Kubota did exactly what Mekas and Clarke prescribed, and she made a tape as close to a document of a “process” as possible. She used a “Totem-Tape” variation by tearfully confronting the video image of her father and the monitor that plays that image. The viewer sees Kubota literally do this and react to it as she makes physical contact with the monitor/image. The tape is affecting; it was made in a home and is best watched in a home.

The Beginning Discovery Re-visited; Video in 2004

Irony #1, Film vs. video: Clarke’s original, then quickly abandoned, dream has come true! Video now offers a cheap, fast, easy technology for shooting, editing, distributing, and exhibiting film. The future is probably photo-electronic, not photo-chemical. Final Cut Pro—not Moviolas; fiber optics and satellites—not cans of celluloid.

Just as the first generation of filmmakers sought to imitate the theater—intercutting, close-ups, sophisticated manipulation of time were all yet to come—many early video practitioners, often purposefully, imitated filmmaking. This is still true—more than thirty years later. Commercial video and a considerable amount of non-commercial video are still measured against standards of film (resolution, gradations of the gray scale, sharp edges, the illusion of depth, and so forth). A few months ago, an excited woman, a filmmaker of thirty years now in her fifties, commiserated with me; she doubted video could ever have the definition and richness of film. A few months before that encounter, another excited woman, in her twenties, showcased her new $4,000 digital video camera for me. I asked her about its features. Her first enthusiastic response was about its ability to shoot at 24 frames per second and portray motion—“just like 16mm film.”

This is the kind of confusion that prompts such innocent but nevertheless perceptive comments that describe video as “the too-common tendency…to be either eye candy or failed attempts at cinema writ small.”15Marc Spiegler, ArtNews December 2002, p. 136. It is confusion that Clarke campaigned to elucidate. Just as she claimed broadcast television was film distribution in disguise, much video found in art galleries is film exhibition in disguise.

Less innocent, but to the same point, are, for example, comments by Amy Taubin about a video installation by Eija-Liisa Ahtila. I find it curious that Taubin calls her observation a “problem” when in fact she has uncovered what I would consider a “truism”:

The problem is that it’s the least filmic installations that are the most powerful, perhaps because the pleasure they offer and the kind of attention they demand is so antithetical to the film experience. Ahtila’s work reflects the provisional, betwixt-and-between quality of installation art in general. That’s less the fault of her considerable talent than a condition of art history. Still, it makes you wish she’d try, just once, to make nothing but a movie.16Amy Taubin, “Discovery,” Film Comment, September/October, 2002, p. 11

Irony #1-A, More about film vs. video: Hollywood contrived the wide-screen format to compete with 1950s television. People now want their TVs bigger than life, just like the movies. The last symbolic blow to film-qua-theater came in the 1960s when the twin theaters Cinema One/Cinema Two opened on Manhattan’s East side. The news here was that the screen was not covered by a theatrical curtain when the audience entered the auditorium. The wall-to-wall screen was finally legitimate in and of itself. There was no more disguising that the motion picture was not three-dimensional. Now we are transforming the video monitor into a flat movie screen. We are saluting the coming of the video projector and the demise of the CRT. In the 20th century, as film matured it did everything possible to differentiate itself from theater; in the 21st video is still aggressively doing everything it can to imitate film.

And what will happen to the poor little monitor with its own personality and presence beyond the images it plays, the images we impose on it? The flat screen—no longer referred to as a monitor or a tv—with its artificial, filmic, wide 16:9 ratio, is inching toward victory in a marketing war.

Irony #2, “I’ve never seen a videotape I liked”: In the early 1980s Clarke started making single-channel videotapes. With Joe Chaikin and Sam Shepard, and produced by The Women’s Interart Center, she directed Tongues and Savage/Love. More tapes followed. Did she capitulate? I don’t know.

And what of the TP Videospace Troupe? Clarke accepted a teaching position at U.C.L.A in the mid-1970s. Some of us continued in New York and on tour for a year or two. Clarke had proselytized for putting control of the moving image in the hands of everyone. But two observations have to qualify her dreamy epiphany. First, not everyone wants their home populated by cameras, monitors, and recording devices, no matter how unobtrusive or simple they are to use. Some people would rather work for the Red Cross, run marathons, or perform heart surgery.

Second, no one else is Shirley Clarke. The workshops she led required personality, presence, and temperament; she had a surfeit of each. She was quick, domineering, one step ahead, short-tempered, but with a sense of humor. People described her as difficult, controlling, and ornery. She often appeared cold; in fact she was not. She could, however, spend several days behind her closed door, sulking and speaking to no one, or she could behave like a cannonball and flatten everything in her path.

She identified with her grandfather, an Eastern European Jew and a creative, successful inventor, who designed the self-tapping screw. She had considerable trouble getting along with her mother and father, a wealthy Park Avenue businessman, who nonetheless was the source of financial support for Clarke’s art. After knowing Clarke for a few weeks, I was amazed to realize that the Beatnik creator of Portrait of Jason and The Connection was a Jewish Mother.

On more than one occasion, a student who witnessed a Clarke temper tantrum asked me how I could work for such a woman. I simply replied that she was the closest person to a complete artist I had ever met and there was more to learn from her than anyone else in the business. She successfully combined personal vision, logical methodology, political awareness, self-reflection, and an impulse to communicate. Thirty years later, having met artists of all kinds by the score, I still maintain this opinion.

Can TP-like video continue? Clarke’s approach, arguably, should not depend on a single personality. She was setting an example, consciously asking others to follow her and take video further than even she took it. But it is undeniable that there are only a few people who could lead workshops in the Clarke style.

The TP Videospace Troupe (1971-1975) List of shows and workshops on tour:

- The Kitchen, May, 1973*

- Flaherty Film Seminar, June, 1973*

- Goddard College, July, 1973*

- 10th Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York (Grand Central Terminal), December, 1973*

- Museum of Modern Art (“Open Circuits”), January, 1974*

- Antioch College (Baltimore), January, 1974*

- Wesleyan College, March, 1974*

- Bucknell University (Mass Media Seminar), April, 1974*

- University Film Study Center (at Hampshire College), July, 1974*

- University of Buffalo, September, 1974*

- Open Mind Gallery, December, 1974

- Anthology Film Archives (“Video Toys”), February, 1975

- Baltimore Museum of Fine Arts, February, 1975

- Cortland State College (Cortland, N.Y.) February, 1975

- Anthology Film Archives, May, 1975

- Media Study Center (Buffalo), May, 1975

- Lake Placid Center for Arts, July, 1975

- 12th Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York, September, 1975

- Oswego State College (SUNY), 1975

* Shows or workshops led by S. Clarke

Text by Andrew Gurian