Marina Zurkow: Parting Worlds

Marina Zurkow: Parting Worlds

Whitney Museum of American Art

April 9 2025-January 11 2026

Marina Zurkow’s Parting Worlds at the Whitney consists of three software-based video installations, on the fifth floor gallery and continuing outside onto the terrace. I spent an afternoon immersed in Zurkow’s worlds, reclining on red beanbags in the room containing Earth Eaters (2025) and Mesocosm (Wink, TX) (2012), and walking around the sculptural maritime elements on the adjacent terrace’s The River is a Circle (2025). Each piece is concerned with ecology, time, place, conveyed through slightly different formal conceits.

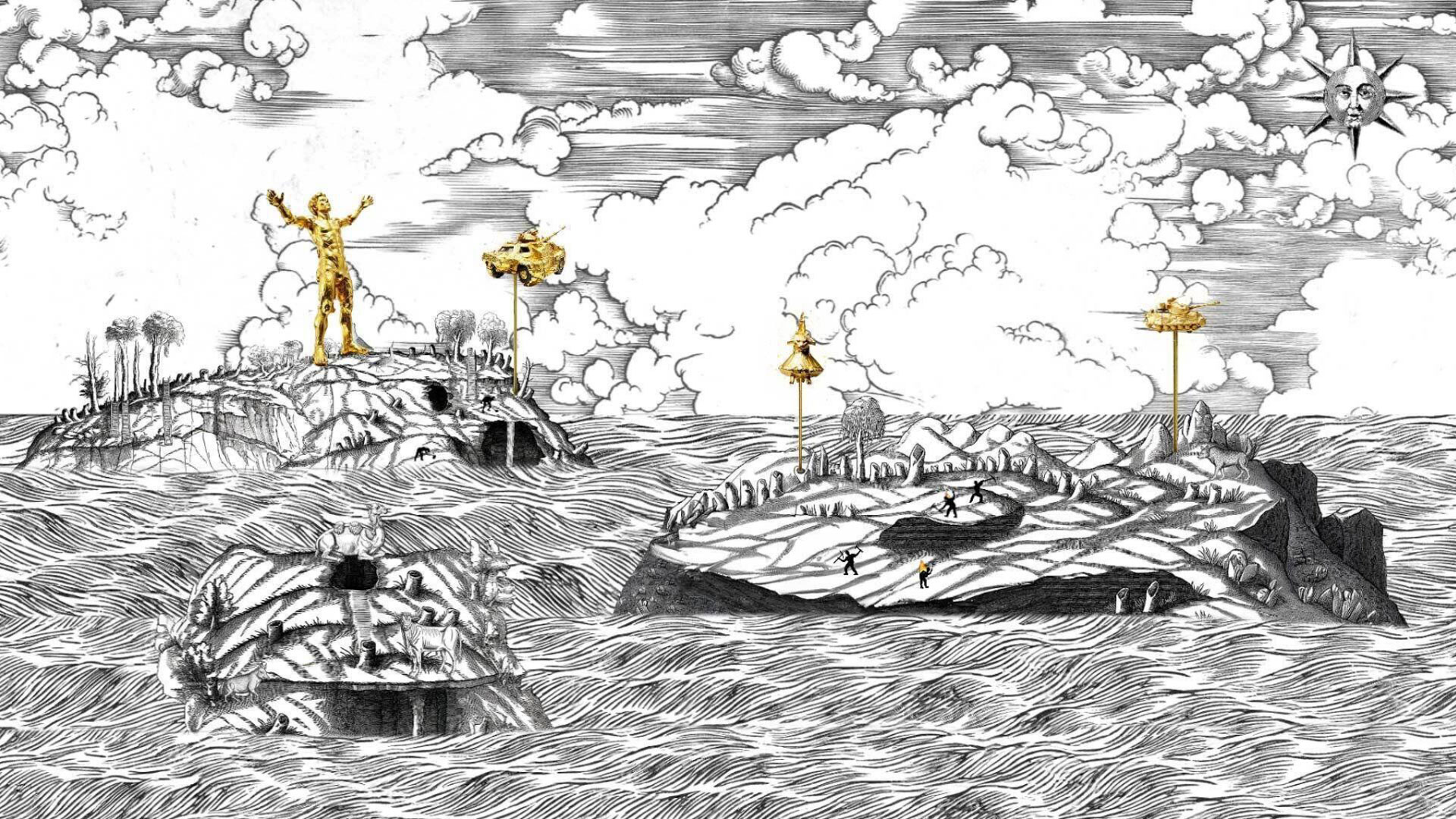

For me, the most resonant was Earth Eaters (2025). Described as a “fairy tale” spread across six clustered LCD panels of varying sizes, it appears at first glance to be a work of traditional hand-drawn animation in the style of black-and-white historical woodcuts. The central image is an ocean of flowing rippling lines, with clouds above and a shapeshifting illustrated sun in the top right. The ocean’s surface is dotted with misshapen islands where shadowy silhouettes swing pickaxes, animals stare menacingly, and golden statues rise. The black, featureless humanoid figures conjure up an implication of slave labor mining—each rote, repetitive swing of the axe producing a small cartoonish jet of flame like a video game interaction. The animals, stately dogs, herons, hyenas, evoke a wild natural order interrupted by the constant erection of oversized golden statues of masculine civilization—men, tanks, cars, planes, rockets. As I was poring over the details, suddenly, one of the islands dissolved into an explosion of particles that disappeared into the sea within seconds. Moments later, a nearby eruption of particles formed a new island, this one smaller, with pseudo-organic juttings resembling heart valves. This dynamic is the piece’s central action, an endless cycle of the elemental creation and destruction of the earth where instrumentalized human labor extracts buried resources to be transfigured into pillars of civilization.

Contrary to its handmade appearance, Earth Eaters (2025) is the product of custom AI algorithms fine-tuned on woodcuts, descriptions of minerals from De Re Metallica (1556), and animal illustrations from Historiae Animalium (mid-1500s). Functionally, this means that the piece is infinitely generative—it plays out in real time, churning out a never-ending variety of islands. Thematically, the use of AI adds another strata of meaning to the piece’s multilayered reckoning with extractive resource cycles. It’s a dizzying dialectic that takes a while to sink in and appreciate, and the piece has other elements that further complicate its meaning—an ASMR-like soundtrack which blends the whispered names of obscure minerals with ambient tones and clicking noises, two screens on the left and right showing an endless stream of aquatic animals, and uncannily organic shapes that sneak their way into the rising and falling islands.

Generative art is becoming more and more common in museums, galleries, and across social media. Elsewhere in the Whitney, Theo Triantafyllidis’s BugSim (Pheremone Spa) is a live simulation of a colorful, surreal terrarium with algorithmically-driven bugs and plants rendered in crisp 3D. Triantafyllidis’s work is similarly mesmerizing, but, it does basically look like a video game. Even as generative art finds a new level of renown, it often struggles to escape a certain level of predictability in its aesthetic codes—the hyperpop cyberpunk HD digital sheen may have felt subversive at one time, but it now feels safe. In contrast, Zurkow’s synthesis of cutting edge technology and older analog traditional techniques of illustration and animation pushes Earth Eaters beyond the usual expectations of generative art into territory of genuine depth.

Perhaps because of my enthusiasm about Earth Eaters, I was less taken by the other two pieces in the exhibition. Mesocosm (Wink, TX) is another, earlier software-driven piece, billed as a 144-hour year-long cycle that never repeats. The simple animation style depicts a Texas sinkhole. Picnic tables dot the foreground, a billboard in the background and flaming oil refineries in the distance. A timestamp in the top left ticks forward in fast motion, while seemingly random events happen on the ground. Faceless figures in hazmat suits wander through the desolate landscape, wildlife scavenges, butterflies flutter, a looping ocean animation appears on the billboard, the sinkhole churns. By design, Mesocosm is meant to be a work that you can’t take in all at once, but rather, that you ambiently check in on, watch slow changes occur over time, just like the ecological timescale it depicts. Unfortunately, given my limited time and the attention-grabbing Earth Eaters right across from it, Mesocosm didn’t make a huge impact on me. I did return to the Whitney later and spent a bit more time looking at Mesocosm, then in a different stage, but I found myself once again drawn in by Earth Eaters.

The outdoor commissioned piece The River is a Circle includes aspects of both works—algorithimcally-guided, ecologically-minded, site-specific, colorful—and as a result, my opinion of it fell in between the two. Located on the terrace, The River is a Circle primarily consists of a large flatscreen animation showing the Hudson River, split in half horizontally giving equal glimpse into the world above and below the water. Buildings and wildlife float by, with probability-driven events reflecting the weather, and references to the Whitney’s own meatpacking district (i.e. sculptures of Gordon Matta Clark and David Hammons). I found these “easter eggs” to be a little cutesy, and prefer the modernist abstraction of Earth Eaters to the art world insider references. The terrace also includes fake maritime wreckage, a sittable ship’s bow, and oyster balls. Maybe a small complaint given the Whitney’s larger issues, but the overbearing branding of the Hyundai Terrace Commission also served as a reminder that corporate tendrils are inescapable even with art that deals so explicitly with climate destruction and the extractive cycles of capital. I don’t count it against Zurkow, but the prominent branding couldn’t help but seep into my experience of the work.

Writing about Refik Anadol’s MoMA installation a few issues ago, I lamented the state of AI-generated artwork, hoping that eventually an artist would use these tools for something interesting. With Parting Worlds, and Roberta Friedman Earth Eaters, Marina Zurkow has answered the call. Conversations around AI in art, and AI in general, have failed to make much progress beyond the same repeated questions around authorship, plagiarism, and environmental impact, even while the technology itself continues creeping further into the mainstream. Zurkow’s piece may not be the magnum opus of the AI era but it’s one of the first works I’ve seen that both uses and interrogates AI while still maintaining a unique aesthetic that goes beyond cyberpunk cliches. I didn’t unabashedly love every aspect of the exhibition, but it made me think more than most, and gave me that rare thrill that drives the jaded cinematic spectator, becoming more difficult over time as the fatigue of repetition calcifies—seeing something new.

Review by Vince Warne

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.