Opening and Opening: The Worldmaking of Ben Rivers

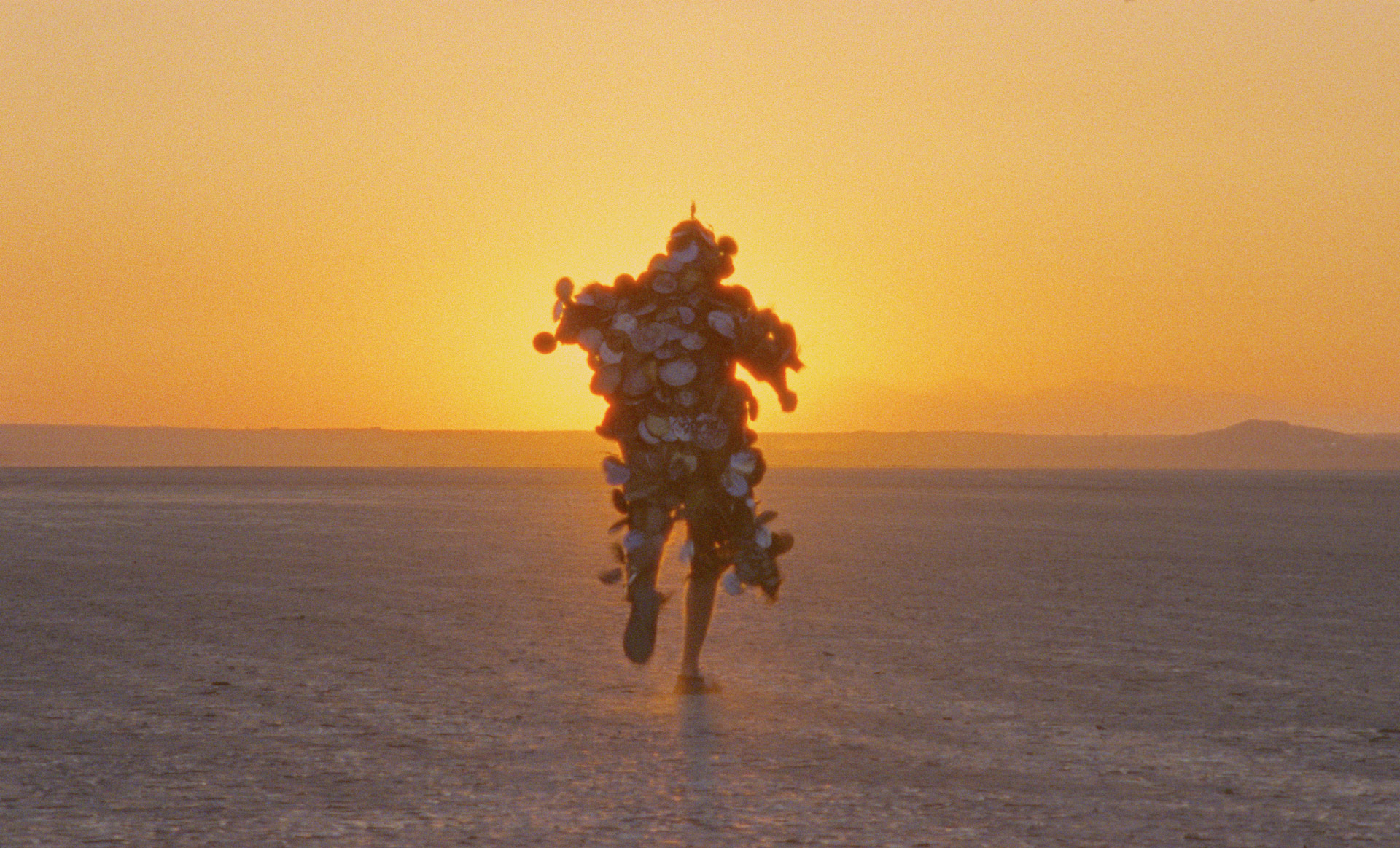

Ben Rivers believes that making a film is a great excuse to spend time with people. In his joint project with Ben Russell, A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness (2013), a woman in an Estonian commune says, “you have to find your people.” In many of Rivers’ projects, but especially his ongoing collaboration with Jake Williams (who first appeared in 2006’s This Land is My Land, then again in 2011’s Two Years At Sea), her adage rings true.

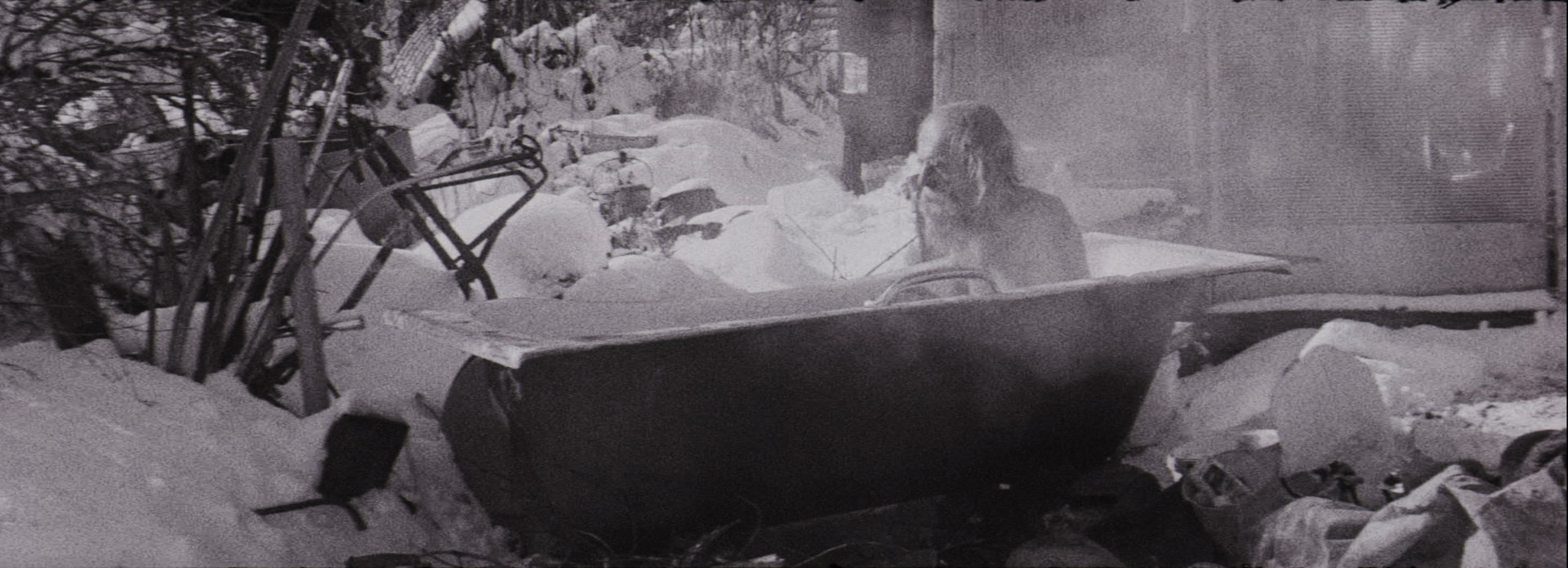

Williams epitomizes the contradictory spirit that Rivers seeks in his subjects: a hermit who lives alone in the Scottish Highlands, but despite his seemingly solitary existence, he loves company, volunteers at the local school, and, in Rivers’ most recent feature Bogancloch (2024), joins a group round a fire in song. “[Connection] isn’t going to happen with everyone,” Rivers tells me over zoom from his London home; yet, watching Williams’ and Rivers’ most recent film, their personal and creative connection shines clear.

Rivers’ peripatetic lifestyle allows him to cultivate connections with a myriad of people during filming, who are typically far removed from the film world and its usual subjects. In addition to being a prolific filmmaker and cinephile, Rivers is also an avid reader who can speak with ease about poetry, prose, or theory. Often drawing from all corners of his eclectic interests, Rivers’s work defies easy categorization, and he likes it that way. His films, at once ludic, oneiric, and deeply rooted in specific, material places, open up new ways of looking and listening — or, in the words of his first monograph, new ways of worldmaking.

I spoke with Rivers in November 2024 about the importance of film clubs for local communities, the abundance of narrative in his films, and being aware of one’s positionality as a filmmaker.

You earned a bachelor’s in fine arts from Falmouth School of Art. Was it in school where you first picked up a camera? How did (or does) your fine arts education inform your filmmaking?

Falmouth was where I bought my first super8 camera. Before then I went to a tiny art school in Somerset, aged 16, to do my art Foundation, a one-year program that helps students transition from secondary school to undergraduate art and design studies.

I went there because I enjoyed drawing and making things, but also because I loved horror and sci-fi films and thought that might be a way to get into making special effects. I grew up in a tiny village in the countryside, so cultural opportunities were pretty slim. But then during those two years of foundation my tiny mind was blown away by discovering all kinds of art, reading, films, music, etc.

I went to Falmouth thinking I might be a painter, then quickly shifted to the mixed media department, which was more open-minded. I started running a film club, showing mostly classic arthouse feature films, then somehow I found a VHS tape of four George Kuchar films called Color Me Lurid, which was fundamental to me. Seeing someone make narratives and collaged non-fiction, with beautiful camera work, humour, precise editing and sound, all on extremely low-budgets, was a huge inspiration. Around the same time the filmmaker Nick Collins came to Falmouth and showed us Margaret Tait, among others, and I remember her films having a marked effect on me. And I was reading Derek Jarman’s diaries.

So I bought a super8 camera from a second-hand market and made my first film for my final degree show called The Big Sink. It’s a black and white contemporary Jekyll and Hyde story, very rough. I was mostly under the influence of Kuchar, and I’d seen Muriel by Alain Resnais. I was driven round the bend with excitement by Resnais’s editing.

You currently run the film club The Machine That Kills Bad People at the ICA alongside Erika Balsom, Beatrice Gibson, and Maria Palacios Cruz. Can you talk about the importance of maintaining a film club in your community? That process of curation feels a bit like editing to me (juxtaposing two separate works together to create a third meaning) – how do you approach the programming of these screenings?

I do feel like programming is part of my creative work. I’ve always done it. After I left art school I went to Brighton and met a couple people who wanted to start a cinema. We ran a cinema throughout my twenties — the Brighton Cinematheque — and showed films four nights a week. I hardly made any films during this period because I was so involved in the programming. At the end of my twenties I realized the time commitment was a bit of a shackle. I needed to concentrate on my own work.

In between that cinema and the Machine, whenever I got invited to do a solo show, I’d always do screenings related to the exhibition. If there was any affiliated cinema for a museum or gallery, I’d say, how about I show some films, not my own, that speak to the wider interests?

A lot of my practice as a filmmaker has been, not solitary exactly, because there’s a lot of collaboration and community involved in it, but I have done a lot on my own. Doing stuff in the cinema is a way of maintaining this community. Not only a community of filmmakers that I speak to as an artist, but also a community of viewers, which I’m also a part of.

The whole project of The Machine That Kills Bad People came out of a frustration with the massive oversight in the history of cinema of films made by women. Our initial goal was to try to bring out films that had been overlooked or lost. But part of our impetus, too, was to show short films and long films without hierarchy and to screen films that spoke to one another, that had some kind of connective tissue.

The Machine is about trying to build up a community of viewers who will come back repeatedly and trust the programming, even if they’ve never heard of the film. People know it’s going to be a certain kind of quality. And they also know after the screening we’re all going to go to the bar and talk. I do feel like that’s an important part of somewhere like the ICA, that you can go out afterwards, though that’s fine if you want to just go for a walk, too.

There’s a recurring motif in your films of origin stories or fables like in The Creation as We Saw It or Things. Your films are recurrently interested in where stories come from, pursuing not a three-act story, but the story’s source. I see this in your eschewal of narrative as well as your shots of prehistoric paintings, wild topographies, or solitary subjects living amongst the elements. Where does the genesis of a project arise for you?

I always find it hard to pinpoint where ideas or obsessions begin as it could’ve started happening long before I even thought that I would make a film. I always liked stories of neanderthals for example, and pagans, because there was a lot of that where I grew up. Stonehenge was nearby. I’m interested in how those origins can talk to now and the future. Like in Things, the film starts with the image of the bird man from Lascaux, and ends with a hand, maybe mine, drawing it on a wall in the virtual replica of my London apartment.

So instead of the three-act story, I’m much more interested in narratives which jump back and forth over vast spans of time, like listening to the geologist Jan Zalasiewicz talk about a contemporary tunnel and what it tells us about a river that was there tens of millions of years before. I also like storytellers like Mohammed Mrabet, who says that his stories change every time he tells them, which is like the stories in The Creation As We Saw It. These tales can change daily and are told differently by different people. In some ways this was a rebellious reaction to the missionary Christian story which was fixed and controlling. That’s my problem with that film, I didn’t really make that clear, so it feels like these might be sacred stories, but actually they’re much closer to satire.

I will say, I don’t eschew narrative. I actually feel like there’s an abundance of narrative in my films, but this gets confused with plot, of which I have mostly avoided. The thing is, I really like fiction and poetry. I read a lot, and I love how texts involve the reader, you can use your imagination. With film, images are obviously more concrete, so I think a way of making a film more generous and open is to avoid those clear three-act plots and exposition. I want space for the viewer to be involved.

The way I work, with small crews which can sometimes be just me, or me and a sound recordist, allows me to spend a lot of time in a place looking and listening, finding shots, and just letting them live without any particular plot meaning or metaphor, they simply exist in this new cinematic world, with a strange new relationship with the shots either side, and with the sound, which can open them up even more. As John Cage said, opening and opening, rather than closing and closing. Even though I start with clear ideas for a film, with scenes and images in my head, I’m also looking to be surprised along the way, to find new ideas, images, or relationships between images and sounds. I’m feeling my way through making a film, and sometimes it is mysterious.

In so many of your films, I delight in what Roland Barthes dubs “the grain of the voice,” like the moment in Trees Down Here when someone starts to gently laugh offscreen or in There is a Happy Land Further Awaay when we hear your own voice interject to have the speaker repeat their lines — can you talk about the texture of language in your films? What draws you to the incorporation of another’s voice?

I’m glad you ask this, because people don’t ask much about it. I’ve used voices a lot, especially in the shorter films. I really love rough recordings, non-professional readers, finding the right tone of voice for what I want to express. Sometimes it’s a recording, and I especially like using old recordings of poets reading their own poems, like in Ghost Strata there’s both W.S. Merwin and Muriel Rukeyser, or Trees Down Here we hear John Ashbery reading his first poem. Then this is accompanied in the same film by my Greek friend Louiza reading the Latin names of trees, which we both thought was funny, these two giants of language combined in her voice, and her laugh.

The narrator of There Is A Happy Land… is the same as Things and Sack Barrow. I never use actors, it’s always about the sound, tone, intonation of the voice. In There Is A Happy Land… I didn’t intend to keep in the directions and the mistakes, the repeats, but in the editing I felt it worked really well with the text (I Am Writing To You From A Far Off Country by Henri Michaux) and with the idea of the film, the near impossibility of describing a place that isn’t your own. In the end it’s very melancholic. Urth is also melancholic, which is narrated by the artist Janice Kerbel. It’s a film that’s possibly about the last person on Earth, writing her journal in a sealed environment, and I listened to various voices until I heard Janice. She had the exact right voice, that was calm, sweet, and melancholic in tone. So it’s never about expertise in acting, it’s always about the sound.

Often, what we’re hearing from these voices in your films is poetry (from John Ashberry to Wallace Stevens, among others). What’s your approach to wedding documentary and literary traditions?

Many of the recordings I’ve used are thanks to the Woodberry Poetry Room at Harvard Library. It’s such an incredible resource, with recordings of all these poets who have passed through there over the past hundred years or so. Reading has been such an important part of my life that it is inseparable from filmmaking, so I want to find ways to incorporate it. Sometimes I simply find a poem that encapsulates the feeling or idea of the film I’m making. For example I had the footage of The House Was Quiet for about five years, but wasn’t sure what to do with it. Then I read Stevens’ poem The House Was Quiet and the World Was Calm, and it all made sense. I edited it very quickly and asked the painter Patrica Treib to read it, which she recorded on her phone and sent to me across the Atlantic and it was perfect, which I knew it would be because her voice is so calm.

Also, There Is A Happy Land Further Awaay (by the way, this title is taken from Krazy Kat, when Krazy sings these songs to himself as he’s wandering about). I went to Vanuatu with Ben Russell and we shared a camera and both filmed lots of things. The idea was that we would then go home and edit the same material separately. I really love this idea because it easily illustrates the power of editing to change a story, meanings, relationships between images and sounds. Ben edited his quite quickly but I got really stuck, struggling with this often quite beautiful footage from a place I felt very disconnected to once I returned to London. I like to go back to places, and one month with no chance of return, because it was so expensive, made it difficult for me to edit. But then I read the Michaux, and again the film suddenly made sense, I knew what to do. The power of the words, describing a place in epistolary form, that the writer could never quite grasp, mirrored my own feelings about the filmed material.

In August 2024, for In Review Online, you spoke about your relationship to the term “documentary,” in regards to Two Years at Sea and Bogancloch. You stated “At no point did I think, ‘I’m making a documentary about Jake.’ It was more about making a film featuring a human, surrounded by all the stuff they’ve accumulated. The human is a part of that stuff. But it’s not a documentary. I’m not trying to illustrate his world or make an accurate ‘document.’ It’s something a bit more transformative.” I’d love to press you now: if not “documentary,” then what? Or is the eschewal of terminology and labels part of the point of these projects?

I prefer to eschew terminology for all my films, especially for these films with Jake. I’m not really into putting the films into boxes. Other people can use terms, but for me I’m simply making films. When my friends and I were running the Brighton cinema, we showed every possible kind of cinema: silent films, trash cinema, underground, avant-garde, commercial Hollywood, repertory cinema from all around the world, queer cinema, horror, etc. That was my film school. My influences were ten years of cinema, mixed with reading and seeing art and everything else in life. It’s more interesting to me to mix all these things together.

With my films with Jake, there is a great deal of observation going on, but that usually happens before I film. I spend ages looking and listening. Then, if there’s something non-human I see and like, I film it, like some special light or a bird. But the majority of the filming with Jake is organised: I work out the scene, the shots, where he will be, and so on, so it’s also a construction based on my choices, and talking with Jake. It feels weird for me to call that a documentary, because it’s also a fiction. This is the way I’ve worked throughout, with varying degrees of playing with the reality of where I am filming. There are a couple of films I feel happy to call documentaries, like the portrait of Rose Wylie, What Means Something, which is more of a straightforward meeting between Rose and me.

If we return to this concept of “the grain,” you work almost exclusively with 16mm film. So often your films transport me somewhere new – whether a locale I’ve never been before or an intimate experience up close as in Two Years at Sea and Bogancloch. When I think about the indexical trace of light on the film strip, the decision to shoot primarily with film feels like an attempt to carry a physical remnant of that experience with you, like a souvenir. I’m curious what the materiality of film means to you personally and for your praxis?

There’s definitely an excitement about making a physical record because the places I am interested in are very physical, they’re not clean, crisp-lined places. They’re often messy, with layers — some dirt, dust, water. And I like that celluloid is real, tangible, not numbers that can disappear more easily. Then there are pragmatic aspects to film which actually really help me, like the length of a roll of film, and the length of shot, which depends on the camera. I use two cameras – with the clockwork Bolex the maximum shot is around 26 seconds, and with the Aaton it can be 12 mins. These shot length limitations are quite useful in thinking about the rhythm and editing while filming. When I’m thinking about a shot or a scene I decide on the camera, using the Aaton if I feel like it needs more time, or if it needs sync sound, then I film for what feels right looking through the viewfinder. The other thing with film is that I feel it adds to this idea of transportation you mention, taking the viewer into something somehow unfamiliar and more cinematic. Black and white helps with this too. So with Bogancloch I wanted to make something that feels quite dreamlike, with smoke and fog blurring the edges of things, even when Jake is doing something quite quotidian.

What do you think draws you to these spaces of isolation as an artist?

I think it has something to do with my personality. I love living in London: the mess, the people, the mix. But every season I go to Somerset and walk on my own. There’s something a little bit Gemini in me about never deciding on one thing or the other. I need them both. I wonder if that’s partly influenced my life as a filmmaker and programmer – that I possess these two separate sides.

I do like to find these people and places that are quite isolated and solitary. But at the same time, I’m quite careful when I meet people to get a sense if they’re misanthropic or not. Like, if that’s their reason for being there? And I have met a few people like that, and I haven’t made a film because there’s not a spark there, I don’t warm to that. I think that’s why I’ve gone back to Jake many times – he’s not at all misanthropic. He loves people, he loves company; but there’s also been this strong need and desire to be in nature, in charge of his own space and time. And sometimes that’s at the expense of the community. So he tries to find ways for people to come there. I’m interested in that contradiction.

I like a landscape where you can just feel the space. I’m not attracted to sterile places or more urban environments. I live in London, but I want to be in a place that’s not my own. Which is a complicated position as a filmmaker. That’s something we’ve rightly been taught to question. But I believe in it; I think it’s important for filmmakers not just to be at home putting a mirror on their place. I think it’s important that we continue to move while being aware of our position. I hope that awareness is embedded in my films; these are personal, subjective films, not explanatory or objective filmmaking, not that there is such a thing.

In a 2012 interview with The White Review you said of Two Years at Sea, “I’m much more interested in making something that is not necessarily about that person. I’m interested in working with that person collaboratively to make something new, to make something that exists just for itself.” Do you feel like you approached Bogancloch similarly? There are subtle shifts (the introduction of Jake’s voice, the inclusion of color, etc.), but the overall styles and aims feel quite similar in some ways. Where did you find novelty with Jake in this shoot the second time around?

It was easy, I would visit Jake sometimes after making Two Years at Sea and would get excited pondering the idea of returning to film, thinking about how the world was changing hugely, while Jake’s life changed more subtly within his place. On my visits Jake and I talked about the possibility of doing another film, and when ten years was approaching, I thought it was time. I approached Bogancloch in very much the same way as Two Years at Sea, in that I’m not wanting to explain his life. The films are in the present, they’re episodes in a possible life, which is close to Jake’s but not entirely accurate, but there is truth to them. I like the idea of a really long-term project, which is also a friendship. One of my first short films was with Jake (This Is My Land, 2006) and it feels like a privilege to be able to go back and spend time with the same person, in the same place, and see how the films change formally, narratively, subtly or not. Superficially it might look similar, black and white, anamorphic 16mm, but in the end I think the feeling of Bogancloch is quite different to Two Years at Sea. Now I can’t get the idea out of my head to make a third feature in another decade or so.

In 2023, Fireflies Press released Collected Stories: Ben Rivers, a collection of creative responses to your films by writers such as Xiaolu Guo, Nathalie Léger, Helen Oyeymi, and Lynne Tillman. How collaborative was the process of creating this book? What were the conversations like that you had with the writers when they were in the nascent stages of their pieces? And what was the experience like of reading, not an analysis of your films, but a reaction?

This publication was instigated by Jeu de Plume in Paris who were doing a full retrospective of all of my films, which was 12 programmes. They asked who would I like to introduce each of the programmes, and I came up with a list of fiction writers and poets. These forms of writing have had such a huge influence on my life and work, and I wanted to include that into the programme.

All the writers I asked were obviously ones I admired a great deal, and quite a few of them didn’t know my work at all. So based on my feelings about their writing I chose a film or two to send to them, so they wouldn’t have to watch loads. Actually for some writers it was really clear to me that I wanted them to write about one film, like Lynne and Now, at Last! (the film with the sloth). Other writers like Helen Oyeyemi, Vanessa Onwuemezi and Daisy Hildyard asked for a few, and somehow incorporated more than one film in their writing. But there was no collaboration beyond that – I simply said write whatever you like and don’t feel like you need to describe or even mention the films. Honestly, it is one of the loveliest things in my whole life as a filmmaker to read those pieces, each one so different, brilliant and generous.

In closing, what are you reading right now?

Fernanda Trías’s The Rooftop — I just read another book by her that I really liked called Pink Slime. I seem to be reading a lot of slightly creepy Latin American novelists. And they’re often short novels as well. Like Way Far Away by Evelio Rosero and Not a River by Selva Almada. They’re really great, and the kind of fiction I might like to pursue in my films. Before I got onto this Latin American phase I read most of Joy Williams. Her book Harrow is so amazing. I think it would make a great film as well.

Interview by Hannah Bonner

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.