Eno: Always Beginning and Never Ending

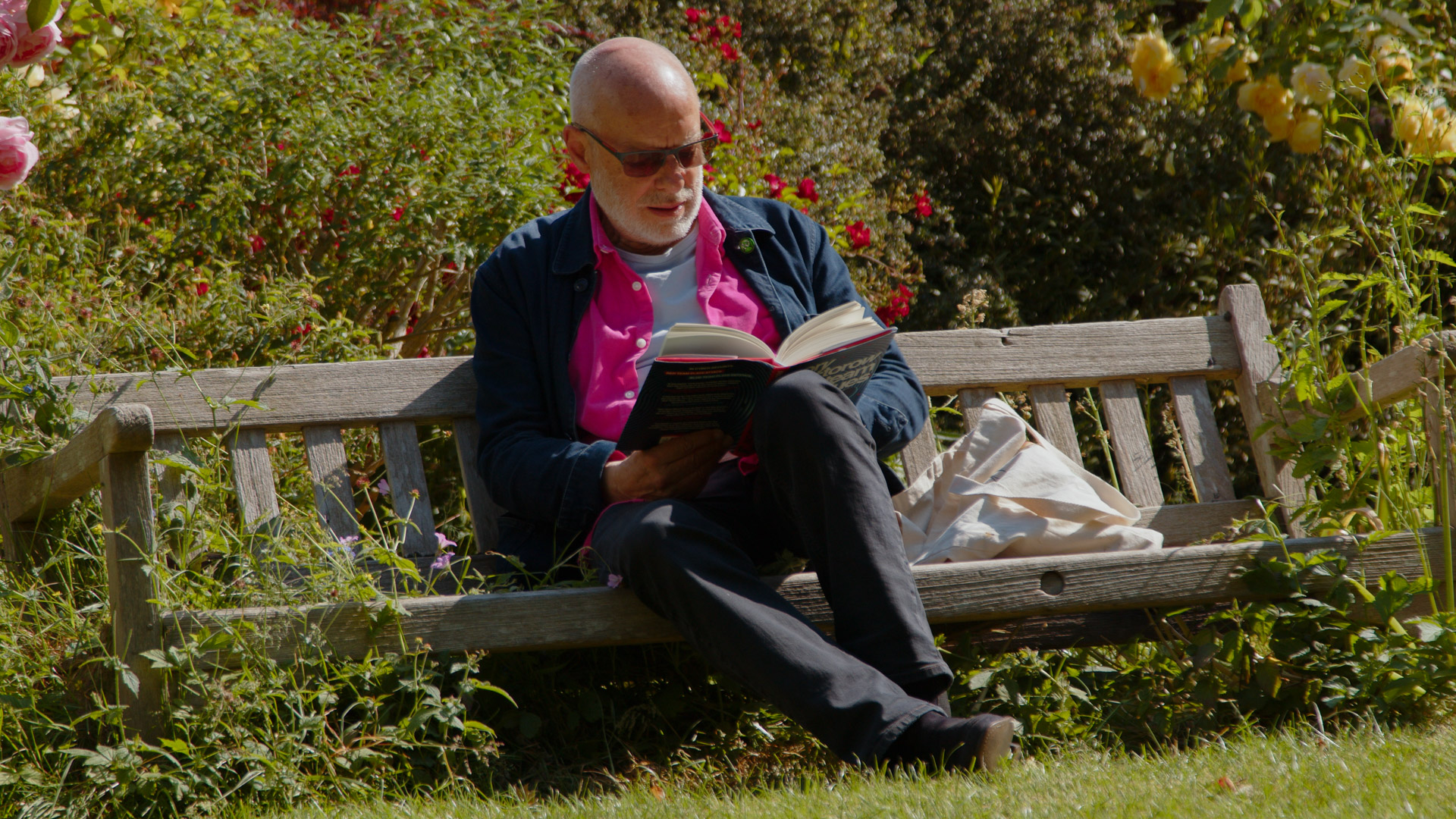

In the generative documentary film Eno, the focus is always the same: an exploration of the life and career of Brian Eno, the visionary music producer, composer, keyboardist, visual artist, and founding member of the British band Roxy Music. However, the film’s precise length, structure, and content varies with each screening. Eno, a collaboration between documentary filmmaker Gary Hustwit, digital artist Brendan Dawes, and film subject Brian Eno, was inspired by the desire to make a biopic that breaks away from the static nature of traditional cinema. For each day Eno is screened, a new film is generated from a set of rules that alter and arrange cinematic content. It uses a proprietary software program called Brain One designed by UK-based digital artist Dawes, which algorithmically sifts through a curated dataset of film content containing over 30 hours of original interviews with Brian Eno and approximately 500 hours of archival footage. This approach allows for the creation of dynamic, evolving iterations of the film, along with new experiences with each viewing. This fluid form circumvents the outdated constraint of a single, static film and shifts toward the creation of many films that are never the same twice, placing the film in a state of always becoming. Eno’s approach to the creative possibilities of algorithmic systems seems to echo Gilles Deleuze’s film theories and philosophy of becoming, borrows from the history of experimental film and its influence on the interactive storytelling of computer games, and reflects the algorithmic creativity characteristic of Brian Eno’s career.

Eno is billed as a revolutionary new form of filmmaking and visual storytelling, but no film emerges from a cinematic tabula rasa. There are hints of the familiar alongside the unexpected throughout the experience of watching it. It incorporates aspects of traditional filmmaking through thoughtfully edited sequences, with a considerable number of them devoted to interviews with Eno. This keeps the film’s structure feeling seamless and sensible, not like a random assemblage of relevant footage. And it fulfills Deleuze’s notion of the time-image, the observation of time no longer being subordinated to movement in film, instead becoming autonomous. In Deleuze’s seminal work of film philosophy Cinema 2: The Time-Image, the possibilities for understanding and experiencing time in cinema shift away from cause-and-effect forms of progression and the idea of cinema as merely a form of representation or narrative. Instead, cinema becomes a medium to express and explore the expanse of virtual space, experience, and becoming. In time-image cinema, the virtual becomes visible through the non-linear structures and fragmented representations of time, memory, and potential futures, allowing the virtual to be perceived alongside the actual. Deleuze’s philosophies may serve as a useful guide to identify the experiences of creative emergence, the nature of becoming, and algorithmic storytelling in Eno.

As AI un-gently creeps into every facet of daily life, one might assume Eno is a product of machine thinking to generate new content, but generative filmmaking is varied and includes a range of methods for creating films using algorithms and other automated systems to generate, modify, and structure various aspects of the filmmaking process. Generative films blend traditional filmmaking techniques with computational creativity, where digital tools contribute to or entirely shape the content, narrative, visuals, or editing. In Eno, algorithms do not create unique footage, rather they generate random or structured sequences, control visual effects, and set up editing patterns. Interstitials between narrative segments show scrambling content pulled from the dataset that is organized into a rapidly shifting mosaic of geometric patterns. This kaleidoscopic effect shows the collision of conventional filmmaking and unexpected visual compositions. It illustrates the selection process of the program, showing the inner workings of a decision tree made with weighted values. Interspersed throughout the film, these transitions are wholly non-linear, non-narrative, and non-orientable, bringing the generative aspect of the film to the fore. They are visually jarring and colorful yet relatively short in duration.

Eno is an exploration of time. Its narrative zigzags through the past and present, using a typical documentary style of interviews with Brian Eno that mostly follow a talking head format. These are intercut with archival footage mined from his decades-long career. There is also a performative aspect to Eno, which unfolds as an event with each generation coming together for the first and only time. Liveness is not critical to the film, as the recording of a uniquely generated film is made in advance of day’s screenings, but some screenings are attended by Hustwit and generated live. Like a musical or theatrical stage performance, there is an element of surprise to each re-viewing. However, despite its infinite variations, Eno never quite feels like an abstract film that follows its own logic, nor does it feel non-linear, because the footage sticks to familiar visual and narrative cinematic conventions. The precise selections of interview segments and recording sessions, B-roll, and performances from the past vary from one generation to the next. Yet every iteration opens and closes the same way, and the film’s total runtime settles around 85 minutes no matter what. This balance between familiarity and variation makes Eno accessible to audiences while still encouraging multiple viewings.

For these reasons, Eno is engaging yet seemingly unremarkable as a single iteration, but its potential for multiplicity and difference is significant and underscores its uniqueness. Its dual existence as a film that begins and ends, and as an idea of a film that is in a state of ever-changing multiplicity indicates its value as an archive and a system worthy of repeated encounters. Viewers have no control over what version of events and archival representation will surface with each screening, whether the studio sessions will be with U2 or Talking Heads or David Bowie. This game of probabilities and possible variations echoes Eno’s own penchant for thinking and creating with systems. Eno’s structure, in principle, employs Eno’s Oblique Strategies, a deck of printed words and phrases intended to inspire creativity. Depending on the iteration of the film, you may see archival footage of David Bowie making a selection or more recent footage of Laurie Anderson. These printed prompts are playful yet serious and serve to function as the thought behind the Thought. Another relevant example is found in Eno’s contributions to generative music, where he uses a system-based approach to composing music that is continuously evolving based on a set of rules or algorithms. In Eno’s generative ambient album Reflection (2017), music runs continuously through an app, adjusting its output based on different times of the day. Likewise, Eno’s generative variations and overall potentialities number in the billions, gesturing toward an automated interactive narrative disguised as just a film. Its structure—an outline of possible scenes and durations guided by algorithmic direction—is the thing behind the Thing.

Eno’s ontology comes into view when examined as a reimagining of other forms that reconfigure time per Deleuze’s philosophical orientation, especially experimental films, computer games, and the areas where they overlap. On the most basic level, films have always been algorithmic. Media theorist Lev Manovich argues that film editing is a precursor to the logic of computing. He draws parallels between the editing process in film and the structural logic of software and computers. Both involve breaking down a continuous sequence into discrete elements (film shots or data), which can then be reassembled in various non-hierarchical ways. Structuralist filmmakers, a group of avant-garde filmmakers who emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, took this idea further. They focused on the formal aspects of film, emphasizing its materiality and structure over narrative or emotion. Structuralist films reject traditional cinematic conventions, aiming to draw attention to the medium itself—its form, process, and the viewer’s perceptual experience. Many structuralist films feature static camera positions, long takes, and repetitive sequences. Others use time and duration as key subjects. By holding shots for extended periods or looping footage, they manipulate viewers’ experience of time, challenging conventional cinematic pacing and exposing the mechanics of filmmaking. Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) and Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma (1970) come to mind.

Recently, Keith Sanborn’s structuralist films explore what he refers to as stochastic montage, an editing approach in which “meanings are generated by juxtaposition and coincidence; this turns out to be not so much a Cagean effect of unpredictability, but a rising to the surface of the unconscious processes operating in the selection of the works for inclusion.” It serves as the organizational logic for his video and multi-channel sound installation work Dreadful Penny Dreadful (2024). The work cycles through over 200 musical renditions of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weil’s famous musical number Die Moritat von Mackie Messer, better known as Mack the Knife, from The Threepenny Opera (1928). Music samples include a range of professional, popular, and amateur covers of the tune and are organized by genres corresponding to color assignments overlaid on repeated sections of a 1931 film adaptation of the play directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst. The creative anachronism in Sanborn’s work is heightened in the stratified audio arrangement, which builds toward a cacophonous mise en abyme, a parallel world nested inside the film that simultaneously swells outward, to create an infinite or layered sense of repetition. The work has a mirroring effect, embedding versions of itself within itself, leading to a sense of self-reference or infinite regress while also emphasizing yet another Deleuzian concept concerning the power of repetition toward the understanding of difference.

Such structuralist-inflected cinematic assemblages employ systems thinking and a database aesthetic, emphasizing the visual and indexical forms of their collected data. Through organizational experiments, the traditional, linear modes of storytelling and expression are replaced by non-linear, fragmented systems that call attention to the underlying structure of databases. The groundbreaking interactive cinema installations The Erl King (1981-85) and Sonata (1991-93) by Roberta Friedman and Grahame Weinbren explore non-linear storytelling through the potential of random access made possible by the newly developed, computer addressable storage capabilities of the LaserDisc. By touching the screen (Erl King), or pointing at the projected image (Sonata), viewers interact with interlocking cinematic narratives produced specifically for the two projects. The installations run on systems developed by the filmmaker team consisting of LaserDisc players, video switchers, and PCs loaded with custom software. The interface is constantly “live” and every interruption by a participant produces a change of image or sound related to the current onscreen moment —an alternate perspective, a different character’s viewpoint, a jump though time, or a voiceover or music change. Sonata and Erl King are structured by dynamic interactions through a collection of audio and video elements. This engagement echoes an editor’s act of film assembly: manipulating the pace, rhythm, and key moments through selections of ready-made cuts, transitions, shots, and sounds. However, the manner of the story’s unfolding is decentralized, negotiated, and endlessly iterative. The participant becomes a collaborator who oscillates between agent and witness in a form motivated by the non-linear way we share stories in real life.

In other examples the database aesthetic and editor’s act is employed more conspicuously, such as in the tangible, encyclopedic nature of Jennifer and Kevin McCoy’s interactive installation Every Shot, Every Episode (2001). In this work, users interact with 10,000 individual shots from the 1970s American crime thriller television series Starsky and Hutch, which are organized by subject and scene type and stored on individually labeled DVDs. In total, there are 278 categories, which reflect a critical analysis of the popular show’s banal objects and stylistic choices alike — such as Every Clock, Every Female Cop, Every Construction Site, Every Tilt Up, and Every Establishing Shot — to recontextualize passive viewership into active consumption. A new narrative experience is possible through the McCoys’ unique rearrangement of the TV series into collections of excerpts and then constructed per the viewer’s selections. In an earlier example of interactive cinema, audience participation takes place through real-time voting. Czech filmmaker Radúz Činčera’s Kinoautomat (1967) involves an on-stage moderator during the screening who pauses the film at nine different points of its duration to solicit scene selections from the audience. This game-like gesture combines the transparency of viewer decision-making with a binary logic that ensures singular experiences from one viewing to the next.

Like generative filmmaking, computer games engender an interplay between submission and control, whereby rules interact and combine to lead to emergent, or unexpected, strategies. Some theorists argue that a computer game is a state machine, a system with laws that govern its behavior and responses to input. It is thus active, in a constant state of transformation. As Janet Murray writes, “Because digital objects can have multiple instantiations, they call forth our delight in variety itself.” Through their encyclopedic capacity, computers readily allow fragments of digital content to be assembled into what Murray refers to as spatial, temporal, and participatory mosaics. Even the least complex computer games store and retrieve vast amounts of information, resulting in a unique playthrough. The line between interactive films and interactive games can get fuzzy. Games such as Dragon’s Lair and Cliff Hanger, both released in 1983, center on a linear succession of QuickTime events (QTEs). These are typically used during cinematic sequences or action scenes and serve to support low-stakes player engagement through on-screen prompts during moments that might otherwise be non-interactive cutscenes. In these cases, variation is limited, but there are countless procedurally generated computer games that result in emergent narratives and experiences. Branching narratives in computer games feature multiple pathways and endings, giving the player agency over how the plot unfolds. In addition to non-linearity, they encourage an increase in replay value. Players often return to the game to explore alternative paths and discover hidden content or alternative endings they missed on an earlier playthrough. The interactive storytelling of computer games like the more recent As Dusk Falls (2022) explores narrative multiverses through a combination of single-player decision-making and through cooperative play using multiplayer mode, in a networked, virtual update to the in-person group consensus explored in Kinoautomat.

These examples circle back to Deleuze’s analysis of the time-image. Deleuze, drawing from Bergson’s concept of duration (durée), emphasizes that time is not simply a sequence of moments but is experienced in a more complex, layered, and multifaceted way. Structuralist films and experimental art turn to unique external structures, and video games seek new ways to incorporate player agency through decision-making. Eno’s iterations begin and end the same and show variation and contrast in the middle of the film. This resembles the framework of a pop song, which abides by the familiar small ternary form, a three-part compositional approach following an ABA structure. Such compositions allow for dissonance to throw off the musical balance introduced in the first part (A), the way an unhinged guitar solo (B) tonally strays from the musical themes of a song, only to transition to a repetition of the opening section (A) to provide resolution. Similarly, Eno begins (A) the same as it ends (A). The film’s middle part (B) is the film’s generative art form, a space of unpredictability. In contrast to deterministic processes, where outcomes are predictable given initial conditions, stochastic processes involve elements of randomness or chance, where outcomes may follow a distribution of probabilities rather than a single predictable result. In Eno’s middle, not all is random. The footage was shot or acquired, edited into discrete scenes, sorted and weighted according to a predetermined overarching effect. Then, at the onset of generation, this data awaits the call to appear in a kind of latent editing process. The film’s potential for disorganization is managed by its core template, a skeletal structure that prevents it from straying too far from a recognizable narrative arc. The format requires that the film include sequences of Eno’s studio sessions, but they could be drawn from any time period and represent any artist without repeating footage in a single iteration. The effect of this format quarantines chaos, keeping it from fully taking over. In an interview following a live screening, Hustwit discussed what audience members thought was a glitch at a previous screening of Eno at Film Forum in New York City. In that iteration, the film lingered for over ten minutes in one of Brain One’s scrambling data mosaics, confusing and irritating viewers at what was perceived to be an unfortunate mistake. It was no glitch, as Brain One’s parameters are programmed to offer variation and flexibity in every generation. But the audience reaction to the lengthy segment is telling. On the surface, this anecdote suggests that only so much cinematic anarchy is tolerated by viewers. However, on closer examination, it signals a deep appreciation for the dynamism the film sets out to achieve and the desire for it to continue without interference. While a rule was not technically broken, this iteration of Eno was not like the others in ways that had not yet been experienced. This novel outcome demonstrates how a little chaos goes a long way, and Eno’s controlled unpredictability is an asset.

The history of film and interactive media is rich with examples of experimentation and reimagining storytelling, the use of moving images, and aspects of duration, tempo, repetition, and anticipation. Eno is a unique addition to this long line of experimentation for leaving viewers wondering, looking for, and experiencing what else is possible. It follows the time-image film theory and the challenge to static conceptions of being to gesture toward a dynamic, ongoing process of change. Reality is not composed of fixed entities but of multiplicities—constantly shifting and evolving processes—and neither is a person’s life, particularly Brian Eno’s. An ordinary biopic would not have been able to fully demonstrate the fluidity or creative rigor of his artistic philosophy, nor produce the kind of active surrender algorithmic creativity encourages. Eno is situated within a lineage of algorithmic storytelling approaches that positions it to reject rigid, binary oppositions in favor of more fluid, interconnected understandings of the life, thought, and creative practice of its subject. In this way, Eno acts as a site and source of potentialities with each generation of the film an actualization of the virtual. Therefore, the cinematic revolution might not be found within the algorithms of Brain One, nor in any single iteration of the film. Rather, it may be found in the data set and its potential for endless iteration toward the emergence of many films, plural. Each single iteration delivers a false totality, planting a seed of continuous anticipation and a refusal of closure. Eno thus exists through parenthetical expression as a film(s) of discrete multiples. Though its moderately stochastic method of assembly is kept in check, it upends conventional cinema through its multiplicity and its existence as a relentless series of this one and that one, all of which go by the same name. It is a film that always begins but never ends.

Review by Natasha Chuk

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.