White Women Are a Curse Against Their Sex: A Conversation with Kathryn Ramey

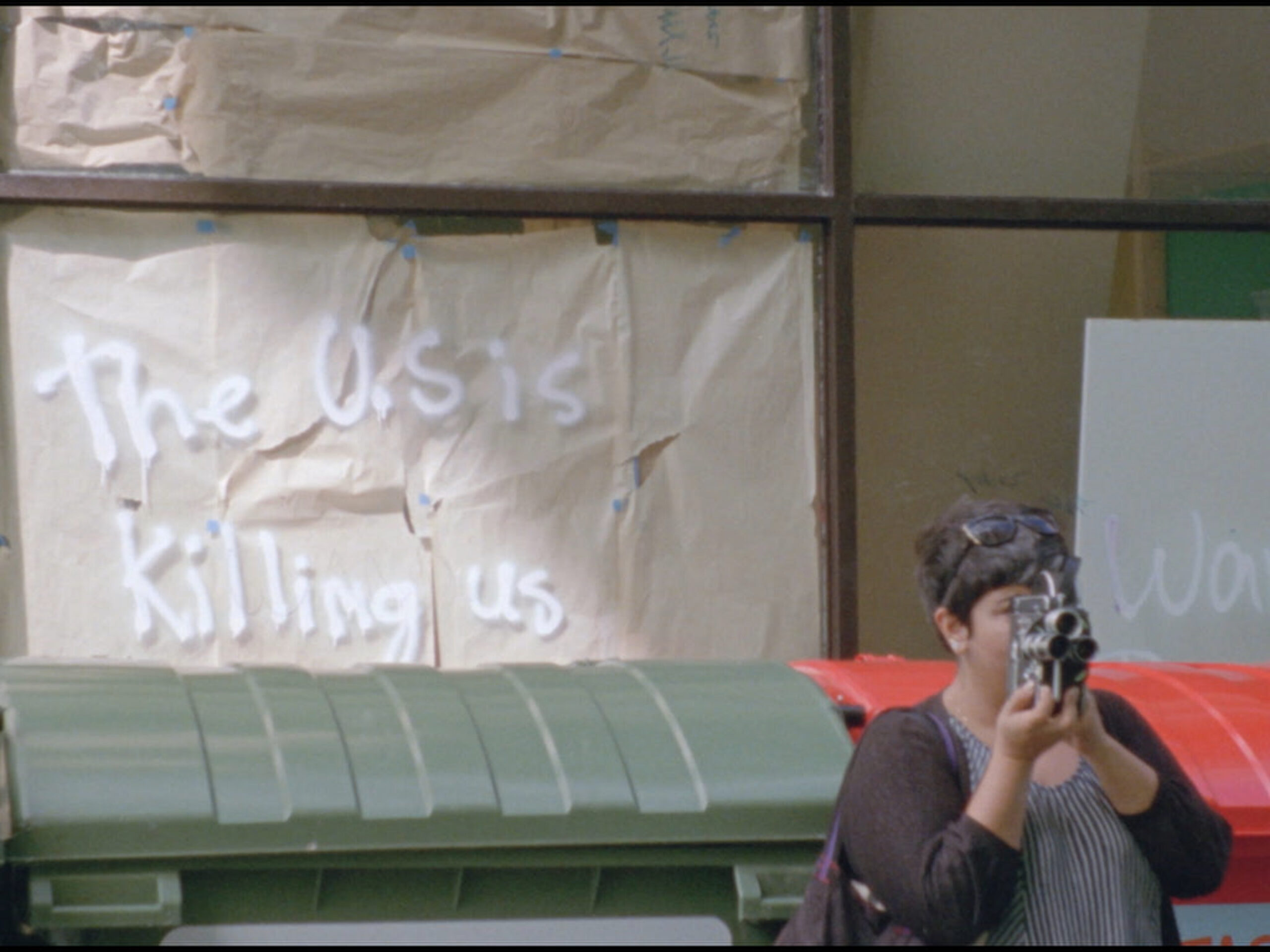

Kathryn Ramey, Excerpt from SAYOR (2022). Image courtesy of the artist.

In 2022, the Revolutions Per Minute Film Festival programmed Kathryn Ramey: White Women Are a Curse Against Their Sex in Cambridge, MA. The program came out at a time of tumultuousness, as the public sphere was filled with rage and confusion over the ruling on abortion by the highest judicial body of the nation. We talked to Katheryn Ramey about the films in this program, which represents two decades of creative articulation of issues such as bourgeois womanhood, race, labor, and reproductive social order in the broader context of capitalist society. With a focus on the feminist and uterus-centered pieces shown in the White Women program, the three of us developed questions and answers together to think about how the films speak to the complexity of reproductive and maternal political, biological life, and the social fabric shaped by women’s reproductive capacity.

Yangqiao Lu

I want to start with a general question about this program. What are some of the initial ideas and intentions when you put these films together under the title White Women Are a Curse Against Their Sex?

Kathryn Ramey

Wenhua (Shi) reached out to me the day after the Supreme Court decision was leaked and asked if I would do a show. Much of my most well-known work including my soon to be released feature EL SIGNO VACÍO (the empty sign) is anti-colonial, but my origins are in personal, experimental, feminist short films, and I have continued to make these kinds of films throughout my career. I chose to focus the show on the arc of that practice and frame it in terms of the contemporary moment.

The title of the show White Women Are a Curse Against Their Sex is actually the name of a short installation that is in pre-production but emerges out of the reality that white women, particularly women of my age and education level, voted overwhelmingly for the conservative Republican white supremacist agenda in the last several elections. Given that they have been the deciding factor in these elections (outside of white men, of course) I wanted to frame this looking backwards to lay down a challenge to myself to make a piece with that title and theme. I was also in the middle of finishing a film called SAYOR, which includes a mother (me) looking at her three assigned-male-at-birth children, and being a little bit terrified about who they might become.

Sarah Keller

Tell us more about that film and its provenance.

KR

The title SAYOR is an acronym for SWIMMING AT YOUR OWN RISK and indicates a forum without a moderator, usually referring to an online forum such as Reddit. There is so much about raising a child that is totally outside your control. So much socialization happens at school or online that you don’t really understand until it manifests itself in behavior. I wanted to capture the moments of these three young people over three summers as they became older and moved into adulthood, adolescence, and older childhood. They were ages 4, 11, and 14 during the first summer, and ages 6, 13, and 16 during the last. So a lot changed for them and in the world. I wanted to visually and sonically capture some of the tensions involved in their transitions and also, of course, my own love and trepidation.

SK

I was struck especially by the formal processes in that film. There are so many superimpositions, and what I’m starting to recognize as a kind of signature of your work, a layer that looks like a film strip on top of the doubly photographed image. Could you talk about that effect and why you do it in so many of your films?

KR

Optical effects are definitely central to my work. I predominantly make what I would characterize as experimental nonfiction. It’s important to me to foreground the sort of sculptural aspect of the work in this process; it is a rejection of various tropes of realism that continue to, surprisingly, resurface as authenticity, despite the fact that Trinh T. Minh-ha wrote her germinal essay Mechanical Eye, Electronic Ear and the Lure of Authenticity 50 years ago. People still cannot get away from the pornography of the real. I love the world as much as anybody else. The world is everything, but I am always processing it through my camera. I’m not interested in fooling anyone into believing that what they are seeing is real. It is made through me and my camera and my editing and sound choices. A lot of the discourse around sensory ethnography still falls into that enchantment with the lushness of reality and sensuousness. You will see moments of this in my films for sure, but I always push the viewer away and remind them of the presence of the camera, the tools, the editing. It’s all made up.

SK

Would you say that this disenchantment of the real is related to your thematic content? Like here, in terms of aspects of the masculine, of raising sons?

KR

Sure. Although I should say, SAYOR was also very much inspired by My name Is Oona (1969) by Gunvor Nelson, an iconic feminist film. Nelson is a female filmmaker filming her daughter in this incredibly free moment, right before adolescence. In 2018 I spent the summer teaching abroad and my children accompanied me, as did a colleague from Emerson. The month after we returned, he killed himself. The same week it happened, I discovered that he had been under investigation at work for sexual misconduct. My family and I spend a week or two in Maine every summer and that year we went pretty much right after his body was found. That was when the first roll in SAYOR was shot. And the design of the film is based on this very first roll of film. So there’s a lot of fragility and anxiety looking at my children and thinking about them as humans who may become cis gendered men—and what that would mean for how they would move through the world.

The idea to create the double exposures was very instinctive. I was at a place after this horrible event with my camera with my children. They were always in the water. I got this idea of water being both tranquil and menacing, and so I would film them and then rewind the film and reshoot it. All the optical effects are done in camera. The film is basically four 100-foot rolls of film strung together. The whole film has eight physical cuts and is a single strand negative. I just made the splices from one thing to another. Occasionally, you’ll actually see a splice in the print and for me that reinforces the film’s constructedness.

The last summer, we were in COVID time and my children and I were trapped in the house. So I took them to the ocean, even though it was winter, to skip rocks. I filmed over that footage in the Harvard Arboretum when the lilacs had just bloomed, and then I hand processed it, which added an additional layer of texture. I did that with the intention of showing how things are breaking down, how I am breaking down. In the beginning things are quite beautiful and very clean. And the film goes to this place of breaking down. That’s where we were in 2020 when the last roll was filmed. Then it took me two years to figure out the shape of the thing and to create the audio from snippets recorded with my kids.

YL

It is an intriguing gesture to submerge your sons visually in the water. You and your films have a certain fascination and entanglement with nature, yet it is not a simple or straightforward relationship. For example, in WEST: What I know about her, the western landscape is magnificent yet so entangled with colonialism and gender. There is something interesting and very complex about situating a narrative about womanhood and labor within a landscape that is charged with connotations of domination, subjugation, expansionism, and colonialism. Can you talk about your relationship with nature and how you see it coming through in your filmmaking?

KR

I grew up in the Pacific Northwest, the youngest of six children in a very small house, so we spent as much time as we could outside. In my film the passenger (2006) you see some footage of my family hiking, and you see me as a baby in a carrier my father made so he could carry his children around when the family hiked, skied, or climbed mountains. Being outside was part of both my heritage and his—his parents were migrant farmworkers. The idea of living and working outside is a big part of my background, as is photography. Both my grandmother and my father were both obsessive photographers. We have photographic documentation from my grandmother and then also from my father who had over 10,000 slides from his life. Probably 99% of them are not of people. Nature is the only culture I had; it was our aesthetic.

I miss the mountains of the Pacific Northwest, the way in which, if it’s a clear day, you can orient yourself based on a mountain. But when you photograph it or you paint it or talk about it, it’s all just a representation. It’s all filtered through you, and it becomes something that can be consumed visually and experienced. That’s part of why even when I photograph it and it’s beautiful, I still push back against letting people get too comfortable. I like to make sure people remember they are watching an image that was made.

YL

I really appreciate your comments at the end in terms of the consumption of nature, especially images of nature and our awareness of it when we are doing that, which is particularly important because the western landscape is very much part of the bourgeois landscape, bourgeois literature, and tourism that are connected to colonial expansion and to the region.

KR

In WEST it seems as though the images are less mediated, but they’re all time-lapse. Anybody who understands motion pictures can feel that. And there are parts of the soundtrack where the time-lapse motor can be heard over the ambient sounds. But there was also an impulse to give the viewer space in that film to feel the camera as a mechanism in relationship to nature. My friend John Gianvito said about the film that you could “feel the presence of the ancestors.” Or, to quote Roland Barthes, the presence of the absence. What is missing—who is missing in those wide-open plains and why are they and their descendants missing? I wanted the camera and by extension the viewer, to be a kind of witness.

Kathryn Ramey, Excerpt from WEST: What I Know about Her (2012). Image courtesy of the artist.

SK

Maybe we could circle back to what you said about the disenchantment of reality. It sounds like you have an impulse to underline the act of filming, while filming, to change the way that things are documented. Thinking about your family history of documentation, this is a new direction.

KR

Well, my grandmother had a sixth-grade education. I know my father went to college, but only because he was on the GI Bill. But my mom didn’t until she was in her fifties. And it’s not to say that one can’t be a critical consumer of images or have an informed and critical working-class perspective on image making, but my family was not that.

I think probably the first mediated repetitive image making that I ever saw was an Andy Warhol print, the one with Elvis at the Portland Art Museum. And then later, I saw a painting (Nude Descending a Staircase) by Duchamp as well as his Ready-mades. Without reading that much critical theory, those works transmitted to me a significant suspicion of reality and the art world and how to be an active and engaged and critical viewer.

And then I actually did go to college, at Evergreen State. That’s where I first picked up a motion picture camera. I thought I was going to be a painter, but then Sally Cloninger came into my studio. I was making these tiny serial images, and she said: “You are not a very good painter, but you’re going to be a great filmmaker.” That is also where I read Trinh T. Minh-ha and so many others and came to understand that the camera was a machine that was translating not transcribing that which is in front of it.

YL

Your films kind of work as an ethnography of parenting, not necessarily through parents as your direct subjects but the image and the voice of children and conversations with them. Can you talk about parenting and filmmaking? How do you work with both?

KR

It’s really challenging to fit all of this stuff into one life, to accommodate the people I share my life with. I feel as though it’s incumbent upon me to prioritize their happiness, which often means working around them. But they fall into my frame when it’s appropriate. My Bolex has come along on many vacations. And it wouldn’t be that way if my family didn’t exist. Unfortunately, when women make films with their children, they’re often relegated to the category of less important things—that thing that she did when she was busy doing other things. I remember I was a respondent for a screening of Lynne Sachs’s Photograph of Wind, and I talked about it in relation to My Name is Oona. Afterwards a person castigated me and said, “Why did you bother spending so much time talking about that film? It wasn’t a serious film. That’s just something Lynne made while she was parenting.” I was so struck by that. Because the film signifies incredible perseverance and will and connection to both her artist and parent self.

SK

Do you feel like personal filmmaking is political filmmaking?

YL

Yes, I particularly appreciate your efforts to seek and draw out political agency out of your work.

KR

I consider my films extended arguments about a variety of things. I want people to think deeply about what it is they’re seeing and hearing. That’s the most important thing I could do. I do think my work impacts people. For the piece that I’m making right now about the US occupation of Puerto Rico (EL SIGNO VACÍO), I certainly hope it at least educates some people, because there is phenomenal ignorance around that in the US.

I think personal filmmaking is political in different ways for different people. When a heterosexual dude makes a film about his kids, that is very political, in the sense that he ends up getting praised for being present in their life. When a woman makes a film with her children or around her children, or that engages with the act of being a parent, it’s often seen as less significant, less important. That shows how political it is because even now, motherhood is a terrible double bind. When I was expecting my first child, I was told by more than one female filmmaker, “Forget it, you’re done, you’ll never make a film again.”

I also think just being a postmenopausal woman taking up space is actually very political. For me, being out there and being loud and angry and old is actually useful. I no longer occupy the space in the world of a woman that gets paid attention to for any other reason, and it is a gift. There’s something beautiful about being old. Because if someone is listening to me, it has to be in spite of every instinct that they have been told by our culture. That’s political.

SK

This makes me think about your voice in your films. Some things are said or sung out loud, in your voice or through others. Other parts are silent but textual, so a viewer reads and hears it in their own head. I like the way that some films like Fall (2006) eschew text of any kind whereas others show writing, sometimes even as it’s happening, like in WEST. How do you make decisions about whether to voice things or to have things be textual?

Kathryn Ramey, Excerpt from the passenger (2007). Image courtesy of the artist.

KR

Oh, it’s torture. I don’t mind my singing voice. But when there are video recordings of me talking, it makes me uncomfortable. And yet I’m the one who’s saying these things. So sometimes it has to come through the instrument of my voice. It could be singing, whispering, or talking normally. I could be performing a certain way of speaking. And sometimes other people have to say stuff. I think different types of speech hit different emotional registers. So it’s a way of acknowledging that and also playing with it. It’s completely gut instinct.

To be honest, half the time, I don’t realize what a good choice is until long after I’ve already made it. And I find I’m really glad I did something because it underlines this thing or emphasizes this other thing or calls it into question. I’m not an artist who plans all that. I can have all kinds of plans, and I’ll always end up back at a place where I’m responding instinctually first, and then editing. It comes back to writing in relation to making images: and not just editing them, but layering or distressing them. It always has to be through moving back and forth with images and text and all the different kinds of materials that I use.

SK

They’re richly layered and instinctual. And that’s your process.

KR

Yeah, it’s true. But I don’t advise it. It’s totally messy, and I think frustrating for anybody who tries to work with me, any of my studio assistants or editing assistants I’ve had over the years. I need to give them straightforward instructions about how to help. But I struggle with it, and that’s why I probably can never be a more mainstream filmmaker.

Conversation by Sarah Keller, Yangqiao Lu, & Kathryn Ramey

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.