EMAF 2022 Continued: Commentary on Selected Works

The European Media Art Festival, 35th edition, consists of five sections:

- An exhibition of nine media art installations, curated by Inge Seidler

• The International Competition: eight programs of submitted moving image works

• Six Feature films on a range of subjects, each from a different region of the world

• “Implication: On Documentary Ethics”— Three feature length documentaries

• “It’s Rather a Verb”— Eight programs of works that as a principle resist categorization

• Retrospective programs of two artist: Beatriz Santiago Muñoz and Emily Wardill

There is a lot to see, and as in many major recent film festivals, one had to navigate through the offerings, since there are always conflicts between equally desirable selections, and viewing films full-size with an audience often affects one differently than on a personal screen. I decided to focus on the International Competition programs: 28 recent films and video works selected from a submission pool of about 2000 entries (as I was informed by Katrin Mundt, one of the two festival directors). I was interested in finding commonalities, which I suspect reflect biases of selection committee members to a lesser extent than underlying values of the festival itself. I noticed resonances between a number of the films, some immediately obvious, others less so, but ultimately the best I can do in this review is to describe works that moved me—likely reflecting my own biases and aesthetic values. As they say, all views expressed are to be attributed solely to the author.

Three qualities are shared by several of the moving image works in the competition program:

- In many cases celluloid film was an originating medium, even if many of the works were transferred to digital files and finished using the broad range of transformative techniques available even in amateur Non Linear Editing applications. Flash frames, light leaks, visible glue splices, scratches, dirt and other artifacts of analog technology do not add significantly to the aesthetic or concept of the work apart from offering evidence of its original format. On the other hand, the disciplined practice required, heralded materiality and menu-free operation inherent to photo-chemical media are important considerations for the filmmaker.

- In terms of context, the intersectional factors of underrepresented identities—race, gender, class, nationality, economic, global biases et al.—were frequently explicit or underlying subjects of works included. Rightly so, in my view, even if I do nurse a feeling that the entire audience and production group is on the same team, in opposition to the undisguised patent hostility and even danger from the regressive forces that appear to be gaining in power and influence around the globe. Rational, respectful argument and non-hostile disagreements seem an impossible ideal in our currently divided world, so I can’t sensibly demand representation of alternative viewpoints in a festival like EMAF. I wouldn’t want to see or hear them anyway, I suppose, but I am slightly troubled by the idea that there is an ideological barrier around all the events that interested me.

- Like Chiara Caterina’s L’Incanto (discussed in my print review), a number of films and videos in the competition section quote audio and visual materials mixed in with those produced by the artist. Recovered from both obscure and private sources or publicly available on the internet, these archival media are addressed in a broad variety of ways, employing a range of cinematic structures and generating different types of meaning.

Chiara Caterina L’Incanto

Ingel Vaikla Papagalo, what’s the time?

Carl Elsaesser Home When You Return

Jorge Castrillo A Wind Grazes Your Door

Sky Hopinka Kicking the Clouds

Renu Savan Crime and Expiation by JJ Granville, Or How to Shoot an Open Secret

Vika Kirschenbauer The Capacity for Adequate Anger

Paribartana Mohanty Rice Hunger Sorrow

Emily Wardill Sea Oak

Emma Hart Skin Film

Amir Borenstein & Effie Weiss By the Throat

Yulene Olaizola Shakespeare and Victor Hugo’s Intimacies (2008)

Stine Deja & Marie Munk Synthetic Seduction

Images of children running on tarmac are followed by a series of closeups of a building soon revealed as “SINT-PAULUS COLLEGE” in permanent signage on an exterior wall, the letters placed above a mysterious “JUGOSLAVIJA”. Eccentrically cropped images of drain pipes, halls, doorways, and windows shimmering with reflections imply a critical appraisal of the architecture, accentuated when children re-appear, running along undistinguished corridors and playing uncomfortably in an alienating environment. The central section of the film is a montage of archival film clips of the Yugoslav Pavilion during the 1958 Brussels World Expo, making much of futuristic exhibits and enthusiastic audiences: a celebratory vision of a country that will have disintegrated after a devastating war less than half a century later. How the elements of the film fit together and its message remain mysterious . . . until the lights come up. During the obligatory Q & A with somewhat reluctant filmmaker Ingel Vaikla, we learn that after the Expo the pavilion was purchased to be reassembled as an elementary school about 100 km from Brussels. The ironies of the film were not immediately obvious to me; for example its critique of modernist architecture as an instantiation of progress, nationalism and neoliberalism. The filmmaker’s intentions were revealed outside the film in program notes and verbal explanations.

But is this a problem? Should we expect an experimental moving image work in an explicitly Art festival to be self-explanatory? A negative critique is not implied in my description of Papagalo as requiring external data for completion. If it is a criticism, it is one that applies to many of the works in EMAF programs. I will propose that it is a sign of a fresh aesthetic, particularly applicable to current experimental media projects.

Home when you return opens with a film director’s introduction to her movie. But the voice is muted, the track replaced by ultra-clean non-vocal sound effects such as chair scrapes and body movements. The presenter’s face is obscured with a distinctive smudging visual effect—as if it’s an informant interview in a true crime documentary. The director’s gestures are deliberate and actor-y. Her words are interspersed in white texts on a black background like early cinema inter-titles. The set-up implies that the introduced film will follow . . . but one suspects this may not happen. From the first moment the spectator is placed in a space of uncertainty, a space of uncertainty. The sequence culminates in a conventional movie title with an orchestral score: it could be a mid-century melodrama.

But we don’t see the movie. After the A Change of Scene title and credits, the earlier sound/picture relationship is reversed. The soundtrack now is dialogue between unseen female characters while the images are immaculately furnished interiors, apparently deserted, the camera positions replicating a possible storyboard—but minus the actors delivering the lines. So three story-streams are embedded in the first eight minutes of Home when you return: a preamble by an unidentifiable film director; elements of a fiction film that could be A Change of Scene; and documentation of an abandoned house that could be a location study for the movie.

Images inside the house continue, alternating with still and motion portraits of a large family, the soundtrack cross-fading between schmaltzy music and increasingly tense movie dialogue. The sequence culminates in a personal letter describing, in maudlin detail, the last hours of a beloved older family member (and thereby providing yet another story-stream). Then: images of the body of a woman in her deathbed, her face obscured by the now familiar smudge effect. The film has moved from a self-consciously theatrical structure to presumably factual documentation of a death in a family. It is a thicket of multi-temporal merged narratives: real, fictional, enacted, archival.

If this description is bewildering, it’s no more so than Home when you return as a whole. It took several viewings for me—bolstered by social media research—to begin to comprehend the work, and finally to appreciate and admire it. The deserted house is revealed to be Carl Elsaesser’s actual grandmother’s, the family’s former home. When Grammy’s body is shown, the visual effect used earlier obscures the face of the deceased, leading a viewer to assume that she and the film director are one and the same. (Or is the face-obscuring an indication that the person is no longer alive? There is nothing in the film to settle this question—obviously a deliberate strategy by the filmmaker.) The confusion of identities is compounded by a later sequence in which a real estate salesman shows the house to a potential buyer (whom we don’t see: it is set up to imply that the potential buyer is operating the camera). The agent’s spiel consists—inappropriately—of a litany of problems in marketing the property. This extended scene is one of the few seemingly unrehearsed cinema verité style episodes in the film. Is the family home actually up for sale following Grammy’s demise? The estate agent is as real as bricks and mortar. Based on its architectural and decorative style the house could have been the location for A Change of Scene. Except it wasn’t . . .

Forced to assimilate and separate multiple layers of discourse and story, a viewer may experience a special kind of involvement in a cinematic work. Once one ‘gets’ Home… it can be understood as a commentary on the potential amalgamation and unstable inseparability of reality and construction, or of documentary and fiction. The film is also a personal family record and a nostalgic shout out to the bathetic melodramas of the 1950s.

I have devoted so much attention to this film neither because it was the most effective work in EMAF (for me) nor because it was awarded a major prize. As suggested above, I propose that the spectatorial experience of Home when you return is a paradigm for several of the films included in both competition and curated sections of EMAF. It incorporates an implicit critique of commercial cinema, and, as hinted above, perhaps indicates a tendency in recent artists’ moving image.

Jorge Castrillo, A Wind Grazes Your Door (Spain 2021 8′), Archival Material: Recording of dark themed folk songs from Southern Spain

The images are rapid hand-held in-camera montages of a variety of rural and local city scenes, most notably the centuries-old much celebrated Holy Week processions in the Andalusian city of Cordoba. The centerpiece of the procession is a masked figure representing Jesus, carried on the back of a donkey. The film sequences are accompanied by a capella versions of folk songs that tell of misbegotten love affairs, out-of-wedlock pregnancies, revenge and honor killings, and other tragic events. Women invariably get the worst of it. At one point two songs are played simultaneously, the Spanish lyrics incoherent, while English subtitles relate failed loves, humiliations and senseless murders. For this viewer the translated lyrics in the subtitles highlight the inherent cruelties and intolerances at the root of the Religious Procession, though it’s impossible to know the extent to which this is the intention of the filmmaker.

Sky Hopinka, Kicking the Clouds (US 2021 16′), Archival Material: Audio recording of the filmmaker’s grandmother and great grandmother discussing their words in Pechanga, their indigenous language.

Like the three films described above, Sky Hopinka’s Kicking the Clouds was shot on film and displays plenty of visual evidence of its analogue original, but was finished utilizing the advantages of digital video post production. The archival material is a 50-year-old audio recording of the filmmaker’s grandmother and her mother, discussing the pronunciation and meanings of words in the Pechanga language.

We hear the filmmaker listening to the tape with his mother and in the process much is revealed about the three generations of women, especially the filmmaker’s mother. Her optimism and generosity shines through as well as a palpable intimacy between son and mother. The images accompanying the voices are metaphorical with an underlying politic. They include meticulous beadwork pouches, moccasins, watch straps and wall hangings made by the filmmaker’s foremothers, interspersed with clouds in a blue sky, forests, and endless stretches of water, deliberately unspectacular, evoking the tenacity of the natural world. As a whole, the film conveys a sense of continuity over centuries of displacement and disempowerment.

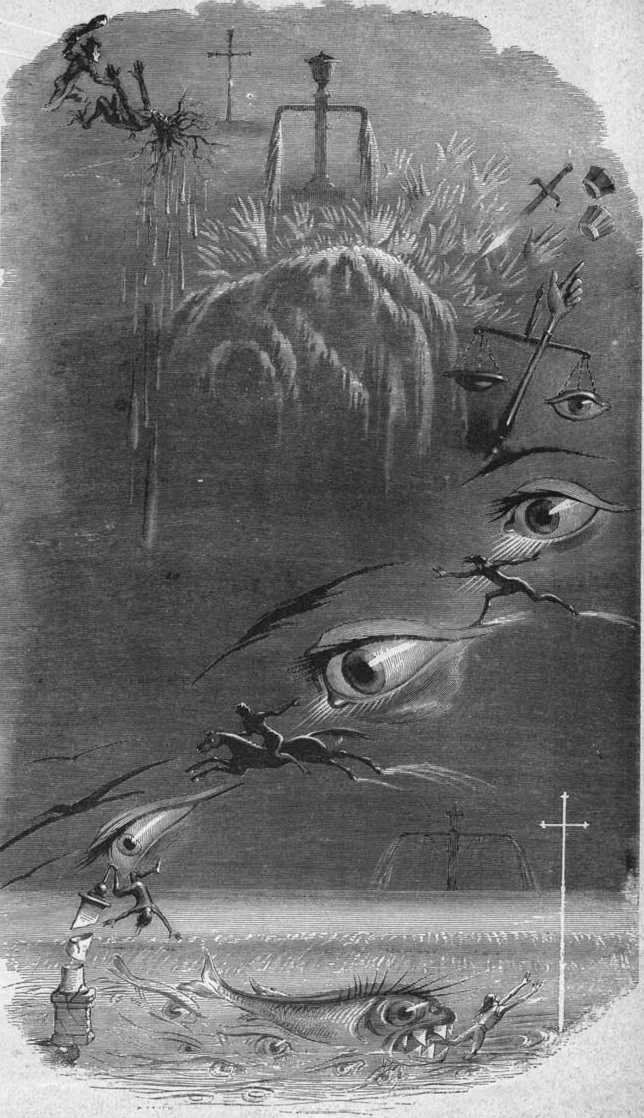

Renu Savan, Crime and Expiation by JJ Granville, Or How to Shoot an Open Secret (India 2021 12:26), Archival Material: JJ Granville’s 19th century lithograph Crime and Expiation.

Perhaps in response to Jeremy Bentham’s almost contemporaneous proposal of the Panopticon, JJ Granville’s lithograph portrays a parade of eyes, one on the next, watching a series of crimes and cruelties. The camera moves down the image, climaxing on an innocent-looking pilgrim unable to reach a shining crucifix (or sword?) as he is about to be snapped up by a giant huge-eyed fish. Addressing the concept of wide-spread surveillance even in regards to fishing, the image introduces a conflict for a filmmaker in recording images of possibly illegal activities with a promise that her footage will not reveal anything useful to authorities. In her narration Savan addresses the ethics of documenting such a scene, resulting in images that may be used as evidence of a crime.

The cinematography deliberately avoids identification of the boat, its sailors, or its location – a near-impossible task. The background, we learn, is that fish are by nature drawn to blue-green light, but that it is against a recent law for Indian fishermen to use this ichthyic propensity to boost their catch. The filmmaker explores the implications and analogies embedded in these facts in interwoven arguments spoken over unfocused, pixelated and underexposed images, mindful to avoid revealing the “who-when-where” of her subject. Again the burden of deciphering the underlying intention is on the viewer, especially in an elegant final scene: a woman ambles around the shore in twilight holding a simple fox mask to her face while the narrator recounts how bands of foxes destroy the fishermen’s catch left in nets overnight.

The Capacity for Adequate Anger opens with a fragment of a manga animation film featuring the golden hair and oh-so-blue eyes of a young beauty. It is an excerpt from The Rose of Versailles (aka Lady Oscar), a film extensively programmed for children’s television in the 1970s and 80s. Lady Oscar, the girl with the flowing tresses, is covertly raised as male in order to inherit her father’s commission as commander of Maria Antoinette’s palace guards. Not named but easily identified through internet research, brief excerpts of The Rose of Versailles recur-—as the only motion sequences—at least a dozen times in The Capacity for Adequate Anger. The work is otherwise composed of stills from archival and personal sources, meticulously placed against the filmmaker’s voice relating episodes of her childhood and artistic development. Connections between narration and images are at first obscure, but progressively resolve into a lexicon of word-image relationships: allegorical, symbolic, illustrative, metaphorical, referential, captional. A viewer comes to understand how the filmmaker’s regretted inability to express ”adequate anger” is intimately connected with the embedded themes of The Rose of Versailles—barriers erected by society and culture in the intersections of gender, sexuality, class, upbringing, wealth and other factors beyond an individual’s control.

Two noteworthy aspects of Kirchenbauer’s narration are: her voice—precise, modest, yet assured, its quality exactly appropriate to an underlying but restrained anger; and the text a treasury of quotable insights. For example:

“How can shame be communicated when all it demands is to hide?”

“I feel an urgency to address issues of work and class but the absurdity is that once one achieves a significant platform as an artist one can only reflect on a past one no longer occupies though the past may still occupy oneself.”

Paribartana Mohanty, Rice Hunger Sorrow, single channel video, 20’23”, 2021 Commissioned by VH AWARD of Hyundai Motor Group, Archival Material: Engineer’s mobile phone documentation of electrical installations destroyed by Cyclone Fani in the State of Odisha, India.

Rice Hunger Sorrow opens with three men and two boys on a beach attempting to balance a gnarled, crooked tree trunk on a pointed boulder. The scene is accompanied by compelling rhythmic percussion. They fail, catching the trunk before it falls to the sand. As allegory, it implies that It may not be possible to achieve equilibrium given the recent disasters afflicting the Odisha coast of North East India. The text “Who is the mightiest of all?” appears throughout the film, over images of decimated structures, fallen trees, and wild tides.

Another theme is threatened traditional culture, with a focus on the Desi dance/song/speech/musical form. The source of the soundtrack for the tree trunk gymnastics is virtuoso Daskathi percussion, simple instruments that sound similar to castanets played by two Daskathia musicians costumed in head-to-toe PPE outfits. They are filmed knee-deep in wild tides and under storm-damaged trees speaking/singing of the violence of nature and man. The implausible combination of traditional music with contemporary lyrics, protective gear, and a turbulent ocean is another effective if not subtle symbol. An engineer swipes through countless mobile phone photos of demolished electrical installations, but his phone screen is soon hidden behind shots of trees torn out of the ground by Cyclone Fani. A pair of cows wander casually among exquisitely painted houses—cornflower blue, scarlet red, jade green, pineapple yellow—in the village of Podampeta. The village is deserted, abandoned due to soil erosion caused by the climate crisis.

Rice Hunger Sorrow sweeps through a panorama of images. It is a spectacular visual and aural treat with a dark and hopeless message. Nature is the implied answer to the question of “the mightiest of all” . . . but does that clarify anything? What will happen to the inhabitants of those parts of the world most affected by climate crises but least responsible for its causes? In a Skype conversation with Paribartana Mohanty I learned that every shot in the film was scrupulously considered and deliberately placed in a praiseworthy attempt to incorporate multiple approaches to documentation of the now familiar set of issues around ongoing climate disasters. A viewer appreciates the attention to detail without fully comprehending the logic of the film or the connections between its images. As I suggest throughout this review, controlled opacity may be a positive aesthetic value in recent experimental media.

A number of other competition films share characteristics with those discussed so far, resting on a base of archival material, visually announcing at least a partial analog foundation, and to some degree refusing to declare the drive, motivation, or intention behind the work or even its primary subject. The strategy leaves the viewer with a sense that there is more than the film reveals, that the medium itself is not sufficiently capacious to accommodate the complications and particularities of the real world. But freed of the imperative to tie up loose ends and edify, educate or convince its viewers, instead referencing information in Q&A sessions, program notes and external research, many works in the European Media Art Festival offer rewarding and unique experiences. I appreciate the approach as a critique of mainstream cinema combined with a development of a fresh aesthetic for artists’ moving image works and experimental media.

Not all films and videos screened at EMAF exhibit the traits I’ve discussed. But most share a common thematic underpinning explicit or buried: issues of identity and the familiar disparities connected with gender race class age wealth ableism, national and/or post colonialist origins… I’m a little discouraged by my own cynical sense that as members of the same ideological team we don’t easily tolerate disagreement, while those who reject our fundamental assumptions gain in power and influence across the world. I don’t know how to navigate these contradictions in my own thinking.

This struck home to me with the exhibition of Emily Wardill’s Sea Oak—a sound work consisting of statements and lectures about language developed by reactionary ideologue groups in the United States. Conservative “Think Tanks” developed procedures to promote regressive positions in part through the co-option of widely used progressive expressions. Articulations originating in forward-looking circles flip their meaning through metaphor, repetition, displacement and context. “Politically correct” is a well-worn example, “woke” a more recent one. Another is “War on Terror:” not a war against a feeling or mental state; but an evocative phase implying a justification of countless aggressive, largely discriminatory operations.

Sea Oak was presented on a spotlit 16mm projector in the center of a cleared storefront space. There was no image, just a small rectangle of light in a concealed corner. Spectators sat around the space watching a 2000 foot 16mm reel unspool while attending to prerecorded statements on a single perf imageless film soundtrack. The concepts presented are familiar, as are the unethical tactics of US neoliberalism—as I’m confident we in the audience all agreed. But what I was I missing in this artwork? Is the metaphor of “watching the apparatus” in any way more transparent than those developed by the Heritage Foundation?

Wardill is one of two artists featured in the festival, her works shown in three programs and the daily Sea Oak installation. I was already a great admirer of her film I gave my love a cherry and I had high hopes, but I was not moved by the range of works in various genres, often visually compelling but not as convincing conceptually.

The antithesis of Sea Oak is Emma Hart’s Skin Film (2005-2007) included in the curated section entitled “It’s Rather a Verb,” which was made up of little known work from the last 50 years or so. The common factor was an inconclusiveness or lack of settlement in the works chosen, a concept that echoes what I’ve suggested as an underlying determinant of the films chosen for the international competition programs. For Skin Film the filmmaker attached cellotape (US: ‘scotch tape’) to her body. On peeling it off a thin layer of skin adhered to the tape, which, exactly the right width, was secured to 16mm film. On projection the film displays a changing series of irregular grid-like patterns, ranging from an elegant latticework similar to the skin of a giraffe to a coarse grate like the hide of a rhinoceros. Occasional hairs span several frames along with other (predictable!) inconsistencies. At EMAF the work was screened as a digital video transfer since the original 16mm film had deteriorated. It is a work of exciting abstraction, a paradigm of lens-free indexicality like a bullet hole or tire tracks, with an erotic underpinning triggered by the viewer’s knowledge of its material origin—contact with a human body.

Lastly, I must mention a few works that were compelling, unusual, and comprehensive—in a word, resplendent. By the Throat (2021) by Amir Borenstein and Effie Weiss is a feature length documentary, its subject language. In interviews with experts of many types and a variety of non-experts, through stories and scientific explanations, the film explores how small variations of speech construction and accent engender substantive practical effects in human relationships and individual lives. I hesitate to give examples not only because I am confident that this film will receive broad distribution, but more intrinsically because it is so rich with extraordinary discoveries, interwoven with fascinating interviews, brimming with jaw-dropping technologies and personal revelations, that it is impossible to select one or two as exemplary.

Shakespeare and Victor Hugo’s Intimacies, produced in 2008 by Yulene Olaizola is another feature film that excited me. It is either an apparent documentary, in fact scripted, or a series of interviews brilliantly arranged to reveal an unanticipated underlying narrative with a shocking ending.

Stine Deja & Marie Munk, Synthetic Seduction (2018), Installation at EMAF 2022.

A work in the installation exhibition took my breath away. CGI graphics of pinkish golden forms rub against one another gently transforming in shape like soft tummies. Synthetic Seduction was “pulsating and carnal” in the language of the artists Stine Deja and Marie Munk. The erotic quality is emphasized by solid shapes resembling whole root vegetables laid out on the floor in front of the screens—hard, fixed, inert, in shape a visual match to the entities on screen, but in sharp contrast to their sensuous flexibiity. Deja and Munk presented other digital videos on a similar theme of nonhuman, non-animal sexuality. All were strangely and uncomfortably erotic.

Osnabrück is a medieval town and the festival takes place largely within its reconstructed walled city, in which the largest buildings are department stores and churches. Almost all the short film programs were screened in the Lagerhalle, a converted warehouse at the edge of the innerstadt. A remarkable feature of the movie theatre is the house lighting. Wedges of blue light originating at the meeting of the rough stone walls and the soaring ceiling illuminate the perimeters of the windowless space, conveying a sense of moonlight leaking through hidden openings. It is a subtle, calming effect which sets a congenial atmosphere for the films and the question and answer sessions.

I was invited to the festival, my travel and accommodation covered. Co-director of EMAF Katrin Mundt assured me that nothing was expected, that I was a ”delegate,” but that they would of course accept a review. In closing I’d like to express my appreciation of the festival’s hospitality, and my congratulations to the entire EMAF team for putting together and running an exciting and unique media art festival. May there be many more!

Review by Grahame Weinbren

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.