Roberta Friedman at FIVAC and Tribeca 2015

Camaguey, the third largest city in Cuba (Havana and Santiago are numbers one and two) is known more for the huge ceramic pots decorating its street corners and hidden alleys than for filmmaking. The old buildings are painted bright pastel pinks, blues and lavenders, some with peeling portraits of Che or Fidel. Musicians play guitars in the streets, and serenade every meal through the open doors of restaurants. Horse-drawn wagons along with ‘61 Chevy Impalas and Russian Ladas transport the locals.

This small historic place, with limited WiFi and virtually no cell service, is the home of the biannual Festival Internacional Videoarte Camaguey (FIVAC). Directors Diana Rosa Perez and Jorge Luis Santana, a soft-spoken married couple, take a hard stand on positioning FIVAC, which they started in 2010, firmly in the 21st- century. They are dedicated to bringing together filmmakers from every continent to present new work, to talk about the state of the art and the culture in today’s filmmaking world, and to take advantage of the recent policy changes in the United States that allows more filmmakers to participate in the festival in Cuba.

Video artists flood this town for a week in the spring, and present short films and installations in storefronts along the recently created walking mall and in the large renovated theatre. Filmmakers congregate at night in the lobby of the local hotel down the block from the theatre and pay by the minute for intermittent WIFI, delicious espresso and a Cuban cigar.

It seemed incongruous that the two films I liked the most and that stirred much discussion at FIVAC this past March were about digital ideas: 370 WORLD and FRAGMENT EDMEMORY.

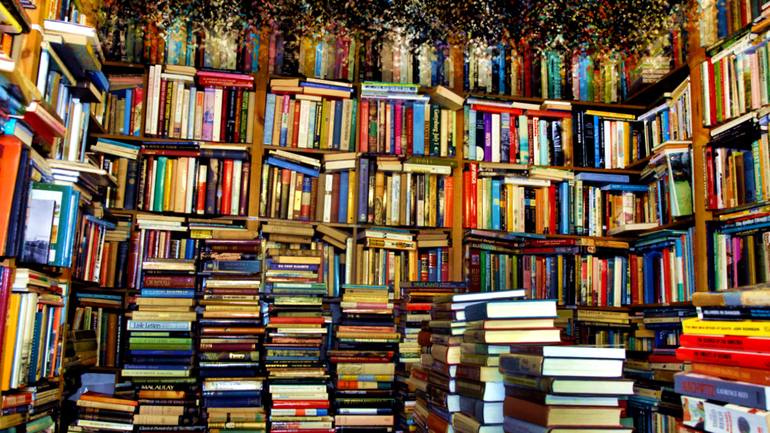

FRAGMENT EDMEMORY, the winner of the festival, was a charming animated film directed and animated by claRa apaRicio yoldi. Stacks of brightly colored, crazily drawn books, haphazardly piled high, completely fill the screen and gradually disintegrate into sparkling pixels that fly into a black sky like a swarm of bees shimmying to a haunting melody, until all of the books have become one big mass of colored dots—a new era where all of our stories no longer live on shelves but on Kindles. Mutated pages re-unite in a digital domain. Although charming, this film projects a melancholy message.

370 WORLD, a film by director Marcantonio Lunardi, opens with a close-up of an old woman whose face is lit by the soft light of the iPad she’s holding. The camera dollies back to reveal her companion, also lit in the soft glow of an iPad. The film slowly cuts between vignettes in subdued earth tones, hues of soft grays and greens of almost no color, suggests a Renaissance painting. Like a still life, people of different ages, barely moving, preoccupied by their electronics, sit around the dinner table, stand in an empty restaurant, chairs piled on the tables, or in the light of a window but not looking out. No one talks to anyone else; the message tells an eerie truth, that no one ventures out anymore. This is a gentle but forlorn and sorrowful prediction of a future without personal interaction. The film ends with a lone man walking across a barren land, holding a bucket and scattering seeds as he walks, perhaps trying to create a new beginning. Human isolation, by now part of the everyday life of many people, is exposed as the director delicately holds a mirror up for us to see it.

This theme of device dependence surfaced at another festival I attended this past year, and I was particularly struck with the unique way filmmakers at two radically different festivals questioned the effect that our electronics have on the human condition. It’s not surprising that similar themes tend to emerge at film festivals each year and that independent filmmakers take up these themes with a creative twist. The four short films I saw were each unsettling in different ways and for different reasons.

The Tribeca Film Festival in New York City in May, and the FIVAC Festival in Camaguey Cuba in March, couldn’t have been more different. Tribeca was industry oriented and commercially accessible, reflecting the noise, high energy level and art of deal making in one of the most populous cities in the United States. Not restricted to one theatre, but several spread out from Chelsea down through SoHo to Tribeca, attendees and festival participants hustled into Ubers, cabs and subways to get to their next screening on time, their iPhones and iPads out, heads down. The New York audience was asked before every screening to turn off their cell phones (not a problem in Cuba: no signal).

The funniest film of the four, BIG BOY, was shown at the Tribeca multiplex. Although a coming of age film about a nine-year-old boy who has a night of adventures in a decaying rest stop men’s room, the film was comic but left a bitter aftertaste. Two parents pull into a deserted rest stop one dark evening and let their chubby son Dustin go into a public bathroom alone for the first time. Neither parent wants to get out of the car to accompany him. While the preoccupied parents are glued to their iPhones, their son interacts with an assortment of strange characters standing next to the urinals: a disheveled derelict who silently retrieves his ball when it rolls under a stall, and threatening looking Rasta guys graffitti-ing the walls. Mom and Dad don’t notice these unsavory fellows slinking out of the men’s room into the dark evening. Their boy bounces back into the car thrilled at his accomplishment: his first solo journey into manhood! But the distracted parents, simply pleased at his return, are unaware of the potential hazards he has avoided. The film ends with a shot of the rear end of the car with graffiti across it painted by the two Rastas, another example of the parents’ obliviousness to what is going on around them.

Whereas 370 WORLD might reflect some aspect of our everyday life, APHASIA predicts a future, should things continue, that is both frightening and harsh. Directed by Luke Lucuro, and written by and starring Robin Rose Singer, the film opens with Emily in her apartment spookily lit as she watches television and texts. A robotic voice wakes her and answers the door— no need for her to talk to anyone. Her life comfortably exists online until she arranges a “live” meet with Austen, a man she only knows electronically. We follow her excitement while she prepares to sing for him, guitar at her side, and eagerly waits for him to meet her at an outdoor restaurant. The shock for her when they finally hook up is that she can no longer speak. Austen backs away. A 21st century Twilight Zone.

Sometimes our dependence on digital devices can benefit us. We rely on our GPS to take us to our destinations with specific instructions, and a phone app to tell us where the worst traffic is going to be. We love the Internet when we want to know a date or make a hotel or car or plane reservation cheaper and faster than ever before. We need our iPads to keep our children occupied for hours on end so that we can have time to read a book.

Sometimes our addiction to digital devices is a bad thing: texting and driving for example (now illegal in NYS) or bullying over the Internet. But what about being too busy with your iPhone to take your kid to a bathroom late one dark night at a deserted rest stop? Or having all of your communication with the world take place only on computer or with texts and Instagrams, and never ever speaking or needing to speak until you don’t have a voice? Or a mother losing interest in her baby’s breastfeeding because her iPad is much more engaging? Or a family at the dinner table, not touching the plates and wine before them but each absorbed in their iPads?

All of these films had minimal dialogue (if any) and maximum meaning.

They were each critical of our wired world: sometimes gentle, poignant, funny or prophetic. But electronic devices are ubiquitous and will become more not less integrated into our daily living. Everyone is a photographer, everyone a filmmaker, texting is becoming the communication of choice. We live in an era of digital saturation bombarded by multiple repetitive images. The filmmakers, while ironically dependent on their own digital devices to create their work, are doing more than reflecting the homogeneity of our world. They are also wistfully reminding us that uniqueness is a thing of the past.

Text by Roberta Friedman