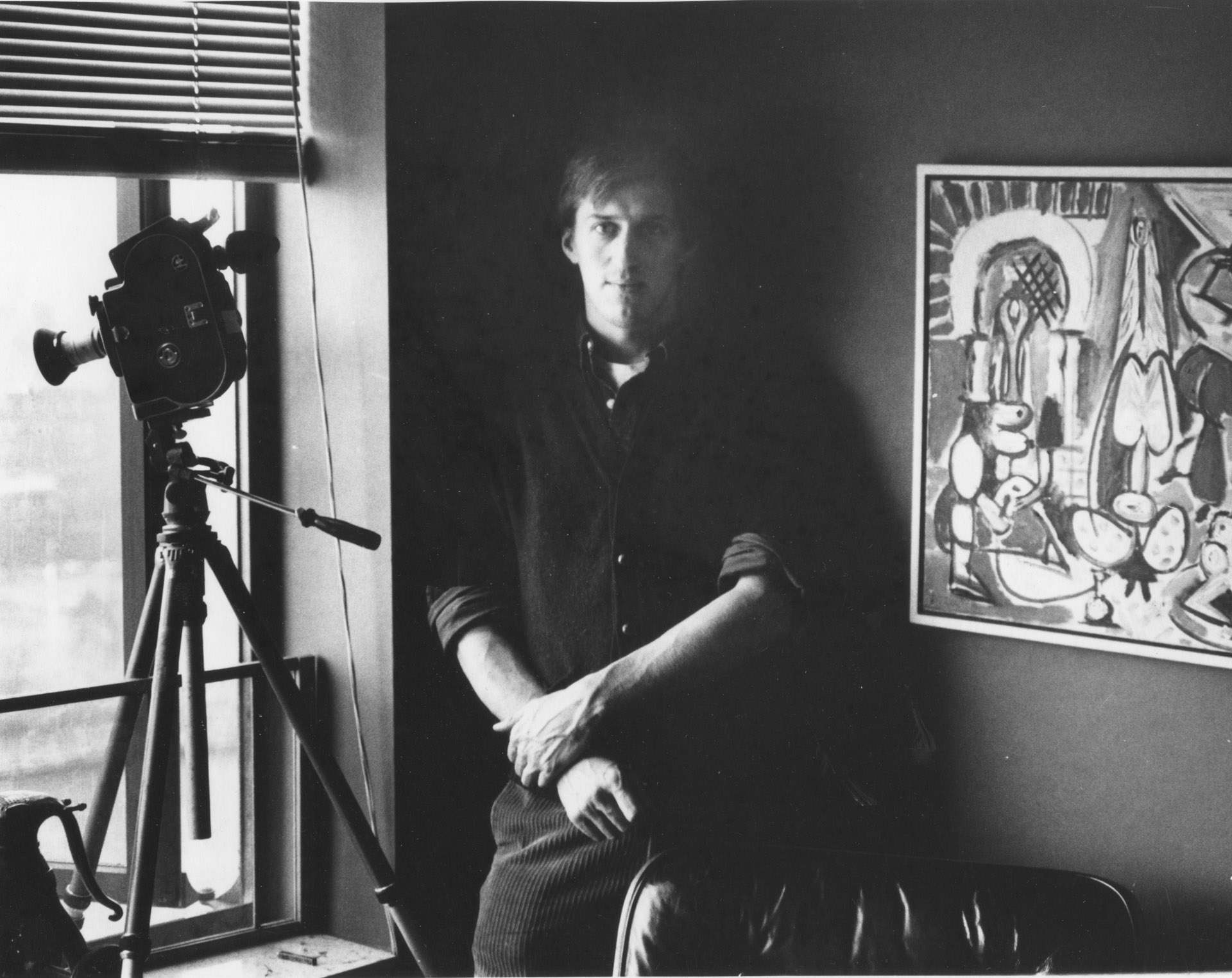

The Long View: A Conversation with Peter von Ziegesar

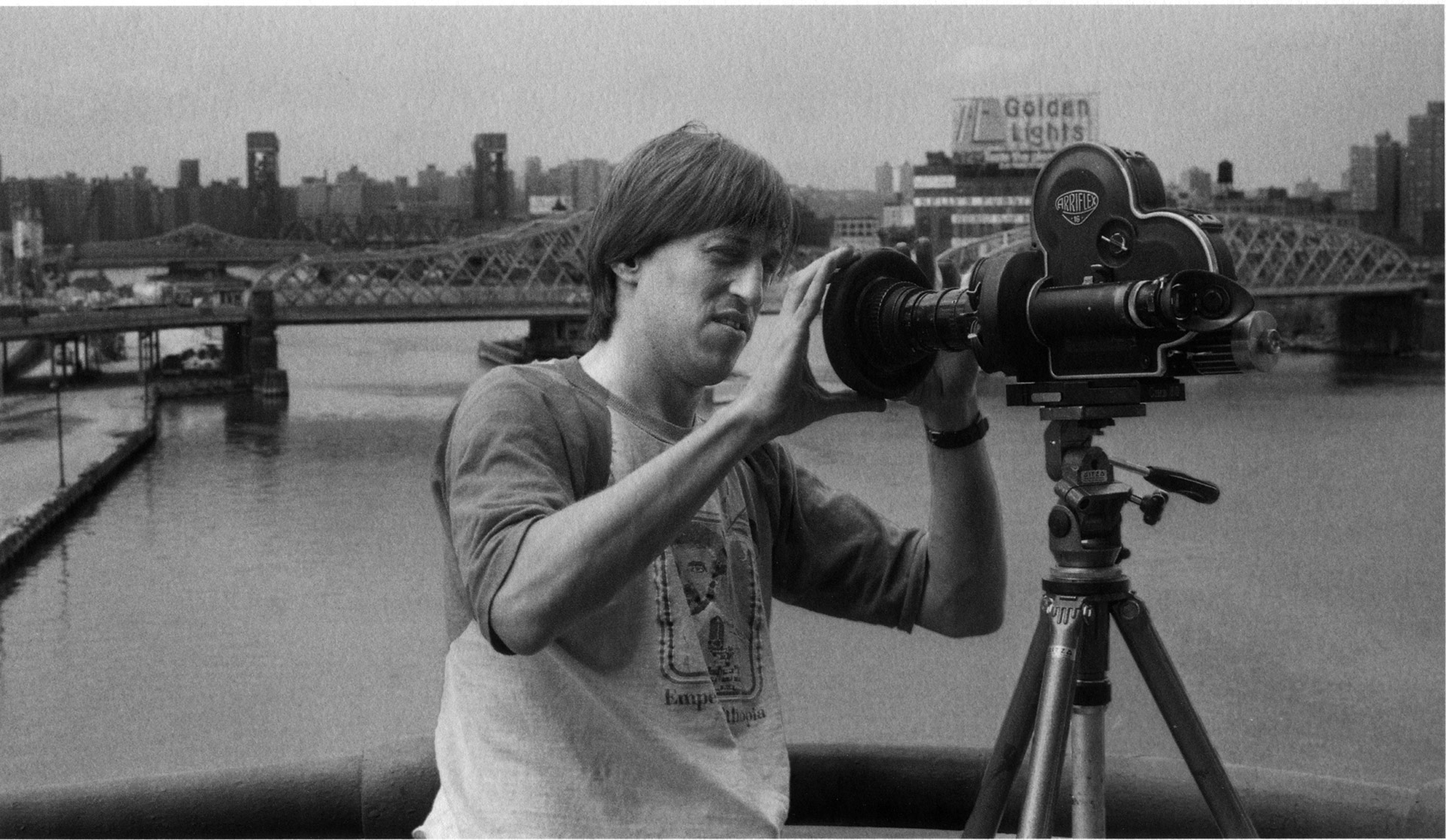

Peter von Ziegesar circa 1980 filming the East River from the apartment of art collectors Victor and Sally Ganz for Concern for the City. Photo courtesy Jim Syme.

Peter von Ziegesar’s Concern for the City (1979–86) belongs in the pantheon of great New York city symphonies. In its reframing of the city in ecosystemic and even cosmic terms, the film is both a reflection of the apocalypticism of the East Village art scene it emerged from and a prescient forerunner of the contemporary discourse of climate catastrophe. And yet, aside from a select few screenings, most recently in “Seeing the City” at Lincoln Center in May 2024, few have seen it.

Despite a significant body of work spanning a decade and a half, Von Ziegesar’s career as an experimental filmmaker is likewise underappreciated. Perhaps best known for his writing, including his art and film criticism and his 2013 memoir The Looking Glass Brother, von Ziegesar also made over twenty experimental films between 1973 and 1987 that run the gamut from cameraless animations and diary films to poetic documentaries. His work has been exhibited at the Hirshhorn Museum, The Collective for Living Cinema, Anthology Film Archives, the Millennium Film Workshop, the 1980 Times Square Show, and MoMA, among other venues. Several of his films are now preserved in the permanent collections of MoMA and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Having written on Concern for the City in my book Decline and Reimagination in Cinematic New York (Routledge 2023), I sat down with Peter in May 2025 to discuss the film along with his body of work, New York’s alternative cinema institutions, the East Village art scene, and the ongoing work of preservation and archiving.

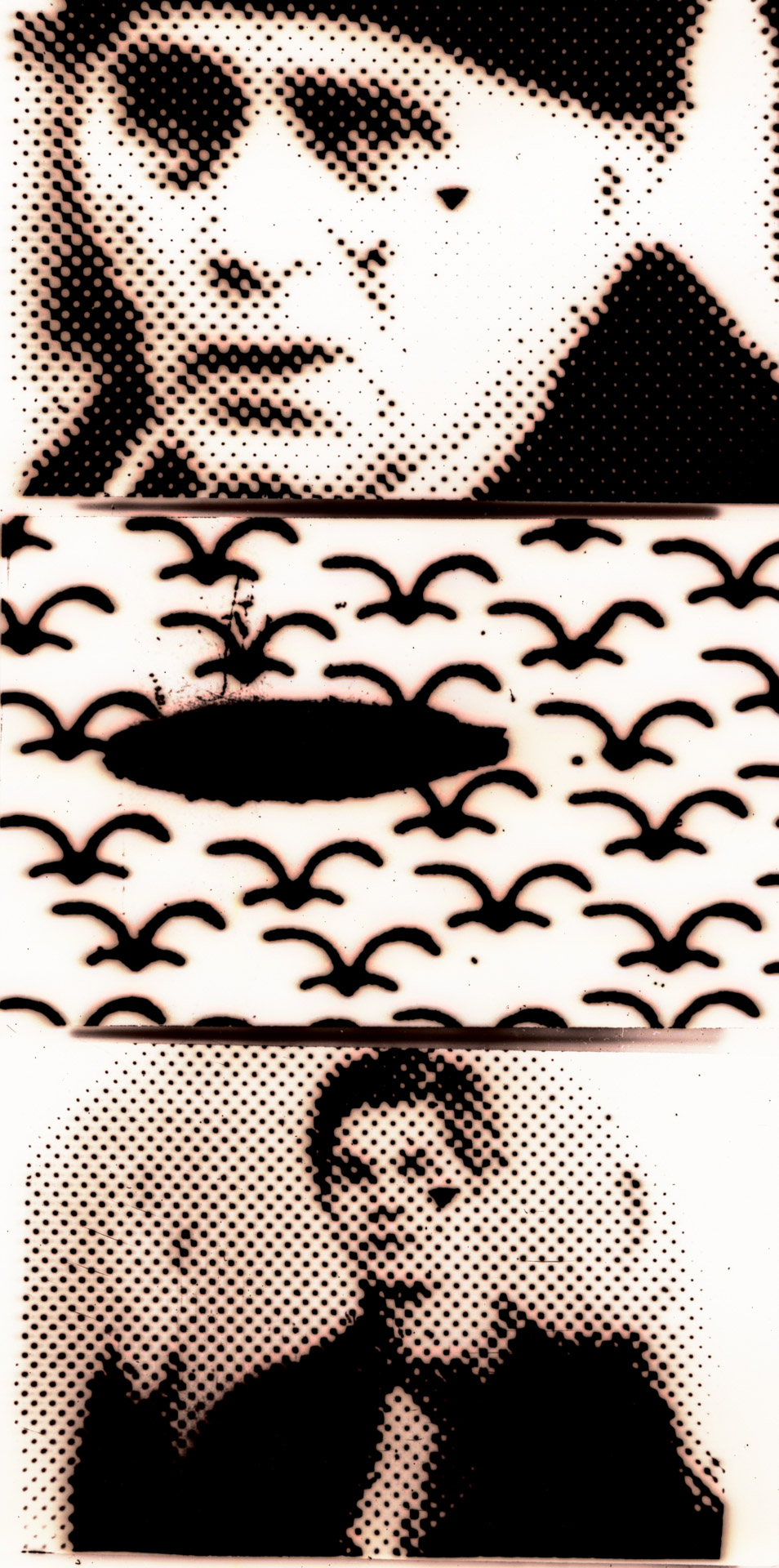

Peter von Ziegesar, Concern for the City (16mm, 30 min, color, sound, 1979-86). Courtesy the artist.

Cortland Rankin: For those not familiar with your work, what would you say are some of your major thematic or aesthetic concerns?

Peter von Ziegesar: I’ve always been interested in symbols and how they relate to the things they represent. My father was a printer, so I knew about halftone and Ben-Day dots long before I saw Warhol or Lichtenstein’s work, and I was fascinated with them as the smallest possible component, the atom, of visual expression. I was interested in getting to the most basic “machine language” of film, like the Abstract Expressionists who were hoping for a direct communication with the human brain or soul on an irrational level. My first major short film Alchemy of the Word (1975) features the artist David Saunders as the French poet Arthur Rimbaud reading from Rimbaud’s poem of the same name. The film, as well as the poem, are about synesthesia, the artist’s transformation of one sense into another, turning light into sound, sound into emotion, and words into images. In that film I applied Zip-A-Tone patterns directly onto clear 16mm stock, including the optical sound edge, so that the viewer sees and hears the dancing shapes onscreen. In The Alphabet (1975), which takes Rimbaud even further, I used a Bolex with an extreme macro lens to flip and roam through the pages of Chinatown pamphlets, Victorian erotic novels, and American pulp fiction, zooming in on lines, phrases, and words. That film is all about trying to liberate symbols from their meanings. I was in a lot of psychic pain as a young man and it occurs to me that in wrenching symbols from their usual contexts and making them dance around and make rude noises onscreen I was in some sense trying to convey my subjective sense of confusion and loss.

Peter von Ziegesar, Alchemy of the Word (16mm, 12 min, black-and-white, sound, 1975), frame enlargements. Courtesy the artist.

I was also interested in isolation and alienation, not only in terms of people living at the edge of civilization, but also in the loneliness and waste possible even when you are surrounded by family and friends. When I was young one of my siblings committed suicide and knowing that he felt isolated to the point where he’d let everything go was traumatic for me. I think you can see this in my film A History of Dancing (1976), which is about coming to terms with the presence of death. The film combines hand-painted calligraphy, shadow puppets and paint-splattered “direct animation,” with footage of women playing tennis and the slaughter of a chicken to explore the transmigration of the soul through several heightened levels of change and regeneration during or after death, which is a theme I’ve explored elsewhere in my films and writings.

Peter von Ziegesar, A History of Dancing (16mm, 12 min, color, silent, 1976). Courtesy the artist.

I was also invested in achieving and portraying higher forms of consciousness. When I was in boarding school I read Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams and the idea that there’s another, symbolic world behind the world we see has always fascinated me. As a result, many of my films try to put the viewer in a meditative state through droning music and repetitive editing patterns in order to encourage them to see or sense a reality beyond that which we normally perceive. Concern for the City is partly about that, as is the second, altered version of Alchemy of the Word (1987), which I created by running the original 16mm film through a prototype digital video synthesizer and adding a soundtrack by the “No Wave” band Liquid Liquid and the German ambient music composer Holger Czukay to create this pulsing, meditational film of lurid colors and dense, finger paint-like qualities.

In my fiction and memoir writing I aim for some of the same concerns I have in my filmmaking—a mythic depth, a kind of trance entry into the subconscious, and a sensory and intellectual grabbing and reacting to whatever is around me à la Joyce’s Ulysses. I am not an experimental writer, however, and tend to use conventional spelling and grammar, as well as comprehensible plotlines and recognizable characters, but you’d be surprised what you can get away with!

Peter von Ziegesar, Alchemy of the Word (Altered Video Version) (video, 16 min, color, sound, 1987). Courtesy the artist.

CR: How do you see your work in relation to larger traditions or canons of experimental filmmaking?

PvZ: In terms of other experimental filmmakers, I felt my work to be closest to that of Stan Brakhage and Harry Smith. When I was attending Columbia College in Chicago in the early 70s to learn film production, I was also regularly attending Brakhage’s lectures at the Art Institute of Chicago, which was really my introduction to experimental film. Mothlight, together with Man Ray’s “rayograph” films, is a direct inspiration for my cameraless animation films like Alchemy of the Word, A History of Dancing, and Just Sprouts (1980). I also connected with the raw intensity of The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes and the simple abstractions of The Text of Light. In making A History of Dancing, my intention was to marry some of the techniques of Abstract Expressionism like direct action, brush strokes, and splatters with the kind of heightened personal filmmaking I’d seen in Brakhage’s Window, Water, Baby Moving.

I was taken with Harry Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic too. You can see the influence of that in Your Death is My Delight (1975), The Alphabet, A History of Dancing, and particularly None Saved (1976), which also presents a journey through a spiritual realm. Smith used cutout animation in Heaven and Earth Magic and I was always drawn to the idea of shadow puppets—in making movies without a camera or projector, in other words. I like shadow puppet plays for other reasons too: for their mythic subject matter, for their length and informality, and for their incorporation of political commentary on current events.

Peter von Ziegesar, None Saved (16mm, 16 min, black-and-white, sound, 1976), frame enlargement. Courtesy the artist.

CR: Could you talk about your relationship to some of the experimental filmmaking institutions in New York that supported you or showed your work?

PvZ: The Millennium Film Workshop not only gave me one of my first solo film exhibitions, but provided me with a community of artists, for which I was grateful. Su Friedrich was a friend from that milieu, and Howard Guttenplan, who directed Millennium for many years, was a friend and mentor. I saw a lot of films there and heard many filmmakers speak, including Kenneth Anger. I also edited several films at Millennium on their Steenbeck, including Alaska (1980) and Concern for the City. I screened early work at The Collective for Living Cinema and Jonas Mekas at Anthology Film Archives gave me my first showing of Alchemy of the Word as part of a group show. It’s funny, because while these institutions were all important to me I also felt a bit alienated from them. They had these pretentious names and were about curating, preserving, and even protecting a certain group aesthetic. Sometimes it felt like they were trying to formalize what was formless by establishing and reaffirming a canon; I could never agree to that. Millennium, it appears to me, has really transformed itself, though; the filmmakers are young, and it seems they’ve kept up. I put many of my films at The Film-Makers’ Co-op, but I don’t know if anybody ever rented them until you did! But some of my films also only exist today because they were at the Co-op, for which I’m grateful.

CR: You made most of your films while you were living in New York’s East Village in the late 1970s and early 1980s. What brought you there and what was it about that place and time that you found so inspirational?

PvZ: I first moved to the East Village in 1974 and lived in a little storefront on 6th Street just off the Bowery. I was interning at Anthology Film Archives and just hanging around. Rent was cheap and food was cheap—you could live off the pierogies at the Polish coffee shops and get a full breakfast for $1.65 at the B&H Dairy. There was so much going on—the St. Marks Cinema showed several different films a day and I saw Patti Smith and Television, among many others, at CBGB. Tina Weymouth (the bassist of Talking Heads) is a distant cousin of mine and I used to go see her play when they were just starting out too. I went back to finish my degree at the Kansas City Art Institute and there was also a strong artist filmmaker group in Kansas City in the 1970s, including David Saunders, Scott Anderson, and Allan Winkler (all of whom are still working artists); we all helped, copied, and played off of each other. When I returned to New York in 1977 with my girlfriend, the sculptor Robin Hill, the East Village was the place to be. We had an apartment on 10th Street and I could see Keith Haring’s studio from my window, the Fun Gallery was next door, and the Pyramid Club was right around the corner. The feeling of freedom was powerful—we were starting our own clubs, galleries, and performance spaces, like Club 57, which was the subject of an exhibition at MoMA a few years ago in which the public access TV show I worked on, Your Program of Programs, was featured. We were a whole generation of art school-trained kids who didn’t fit in at home and were too cool for school anymore, so where do you go? You go to the East Village.

von Ziegesar filming Concern for the City on the streets of the East Village. Photo courtesy Jim Syme.

CR: What was your relationship like to the broader East Village art “scene”?

PvZ: I was as much influenced by Anthology Film Archives and its more academic version of film art as by the East Village art scene, which was against all that; that tore me in two different directions. I was also hanging out at Millennium a lot, but I thought we were sort of the squares honestly. But there was huge variety in the East Village—everyone was in some stage of either being straight or super cool, or being on drugs or not on drugs, or being gay or not gay, or just being halfway all the time. Some people’s ambitions were to stay on the streets and some people’s ambitions were to be in the galleries. I mean, everybody liked Beth and Scott B’s films, and I thought there was something wrong with me because I wasn’t making pseudo-noir stuff, but I just didn’t relate to it. Not everybody in the East Village was a great artist, but the “mulch” they helped create was valuable—the rot in which art could ferment and grow—and no place was more conducive to rot than the East Village in those days. It was a great time to be an artist in New York and I was lucky to be a part of it. I still eat pierogies as often as I can as a tribute to that time.

CR: Can you talk about your participation in the 1980 Times Square Show, which helped announce the arrival of a new scene in the New York art world?

PvZ: The New York artists’ group Colab (aka Collaborative Projects, Inc.) took over an empty massage parlor in Times Square and decided to have a big art show. Rick Greenwald, who I knew from Millennium, put the films together. I screened Just Sprouts and an early cut of Concern for the City. In theory I approved of everything about the show, but I didn’t like everything in the show or even the people all that much—so many of them were forming this exclusive club. At some point, Jean-Michel Basquiat came and graffitied all this satirical “SAMO©” stuff on the walls without permission that put everyone in their place—he was so good at nailing those guys. The show was anarchic, it was pretentious, it was art school, but in a way it really did capture what was going on. It was kind of like a manifesto of the time—we’re going to put our art in the sleaziest possible area of the city, the forgotten zone, the dead zone, and no one’s going to tell us what to do.

CR: You also worked on a couple public access TV programs during this period, most notably Your Program of Programs (1982–83). What did that entail and what roles did you see community-based programming fulfilling?

PvZ: Your Program of Programs was a weekly late-night talk show hosted by Kęstutis Nakas, who was a theater artist. Kęstutis recruited me to “direct,” but I was really camera directing. He grabbed a 10 PM Saturday slot on Manhattan Cable TV, and every weekend we would come out of the shadows like the X-Men and follow him to this ramshackle television studio. The title was a play on Your Show of Shows and it was a spoof of a late-night talk show. We’d have all these downtown artists as guests like Kenny Scharf, Ann Magnuson, John Sex, Tom Rubnitz, etc. Everyone was trying to get famous, but no one seriously thought they were going to get famous, so we were all just pretending, like Andy Warhol’s superstars. We were all doing it for each other and like Club 57 everyone would just show up. We were doing what we thought was valuable, and a lot of it was satire. I remember Ann Magnuson making fun of hippies and I was like, “Can you make fun of hippies? I thought they were cool.” Then I realized “Yeah, you can make fun of hippies. They’re ridiculous.” There must’ve been about 50 issues of the show total but I have no idea who, if anyone, was watching it at the time. But now MoMA has all the episodes in their collection.

von Ziegesar on camera filming Peyton Wilkinson and Timothy Siciliano performing a puppet show for the public access TV show Your Program of Programs (May 1982–May 1983). Photo courtesy Jim Syme.

CR: You consider Concern for the City to be your most significant film. Where did the idea for this film come from and how did you carry it out?

PvZ: I’d first had the idea for Concern for the City back in Chicago in the early 70s, but I wasn’t able to realize it until New York. It’s about my sense of the randomness and anarchy of nature overwhelming the city. The idea of civilization breaking down was so integral to the whole East Village scene. The city was literally breaking down before our eyes, there was the off chance that the whole place might be blown up by an atomic bomb because Reagan was playing chicken with the Russians, and then we found out what a true apocalypse could be like with AIDS. It was a cruel, weird time and I just had this feeling that something bad could happen at any moment and my life would be over. So, like Keith Haring or Kenny Scharf, who both seemed obsessed with mutation and decay, I was imagining, and even celebrating, what a post-nuclear future might look like. I wanted to picture New York like one of those long-lost cities in the Yucatan or Cambodia covered with jungle vines and devoid of humans. I had also read The Starship and the Canoe by Kenneth Brower, where I encountered the term “cryptozoic,” which refers to species of animals, such as raccoons and possums, that live hidden amongst human civilization. Even some kinds of humans can be thought of as cryptozoic, and bear the same relationship to society, such as homeless people, hippies, cultists, and maybe even artists. Christy Rupp’s work on urban animals like rats and roaches was definitely influential in this regard and I actually helped produce some of her video work on the topic. In Concern for the City I was trying to film the city from the point of view of someone who was not of it, or maybe not even in a human frame.

I shot between 1979 and 1982 and it was like shooting a nature documentary. I spent two years with my photographer friend, Jim Syme, climbing around rocky beaches, breakwaters along the East River, going to remote swamps in Jamaica Bay, and shooting time-lapse footage with a 16mm Arriflex camera fitted with a time-lapse motor I built myself from parts I found on Canal Street. I felt very much like Vertov’s cameraman in Man with a Movie Camera. I didn’t show myself in the film, but I had a three-lens mount on the Arriflex and sometimes I would deliberately change the lens while I was filming so the whole scene would lift up and flip around and then there would be a new lens. I did that just to pull people out of their accepted way of seeing. I was trying to make a film that would put the viewer in a meditative state and remove them from the context of their job or commercial prospects. I wanted to dislocate the city and put it in a much bigger, even cosmic, context so that the viewer could see another New York that I felt to be there behind the New York we all saw. The droning electronic music score by Klaus Schulze adds another defamiliarizing, apocalyptic layer to the whole thing. It sounds like we’re on Mars and there’s a windstorm happening and there’s a ruined civilization off in the distance.

von Ziegesar setting up his 16mm Arriflex camera to film the Harlem River for Concern for the City. Photo courtesy Jim Syme.

CR: In my book, I discuss Concern for the City in the context of other experimental filmmakers who were interested in reframing the city through ecocritical lenses like Hilary Harris, Peter Hutton, Rudy Burckhardt, Jem Cohen, and Godfrey Reggio. Were you aware of any of these filmmakers or their films at the time? If so, how did they inform your film?

PvZ: I was aware of Peter Hutton and Rudy Burckhardt, and had seen some of their films, but not their cityscapes. Most of my reference points were the older silent films like Man with a Movie Camera or Berlin, Symphony of a Great City. Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi is another story. I had been working on Concern for the City for years and had just broken up with my girlfriend and she rather cruelly said, “You gotta see this new film because he just did what you’ve been trying to do, only better.” So Jim Syme and I went to see Koyaanisqatsi at Radio City Music Hall in 1982. It was in 35mm, it had a score by Philip Glass and I was like, “Oh, what the fuck! I’m sunk.” Eventually I regrouped and realized that while Koyaanisqatsi was all about how we’re destroying nature, Concern for the City was the opposite—it was about nature encroaching on and taking over the city, and how nature is the reality behind what you see in the city. I can see that now, but at the time I felt like I’d just been killed. It was the last time I picked up a camera for a long time.

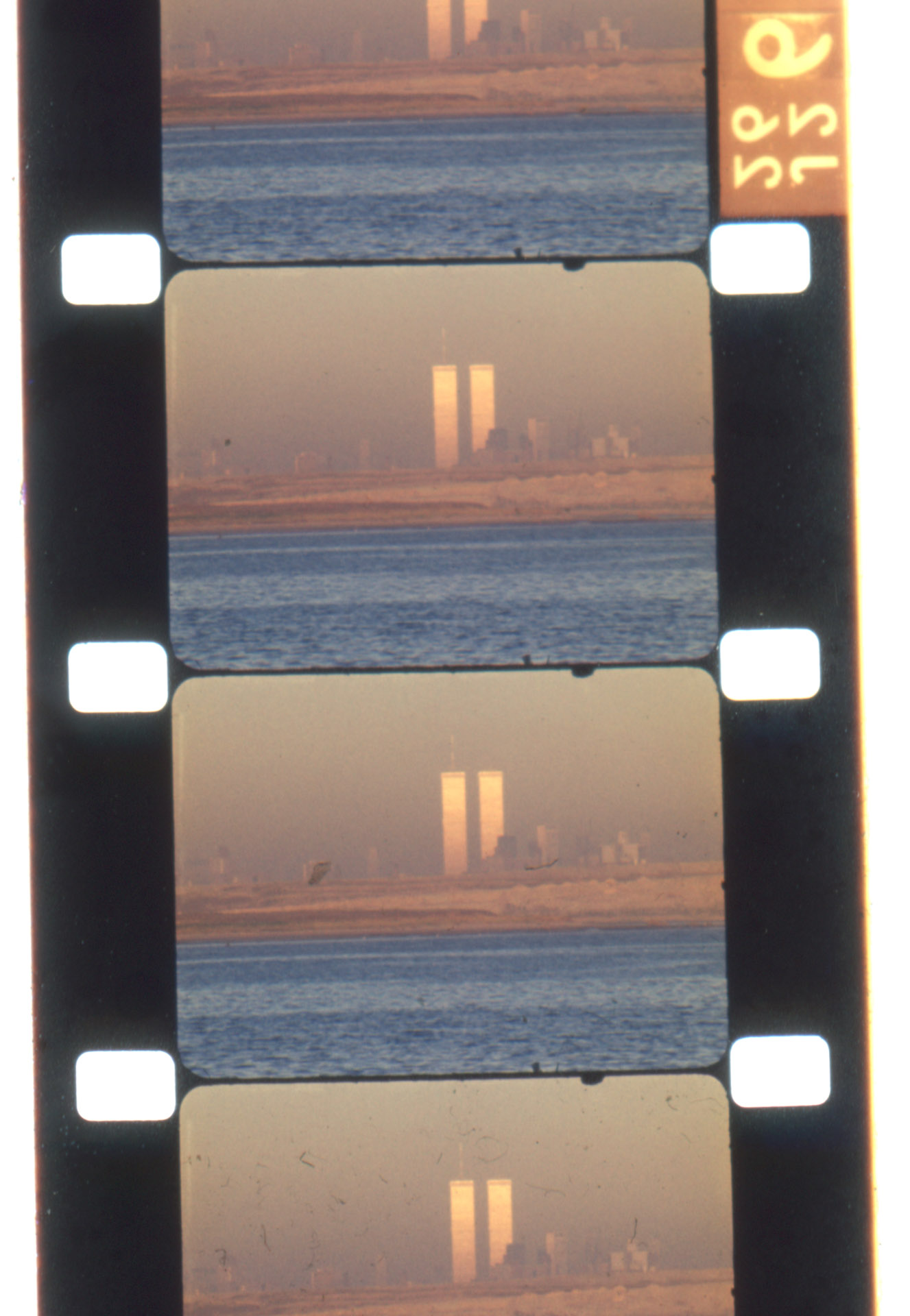

Peter von Ziegesar, Concern for the City (16mm, 30 min, color, sound, 1979–86), frame enlargements. Courtesy the artist.

CR: Can you talk about the process of preserving and archiving your films? What has that entailed and what perspectives have you gained on yourself as a filmmaker?

PvZ: In the old days film processing labs were like public services. You’d leave your negatives there and order prints when you wanted them. When they went out of business they tossed a lot of stuff. Western Cine in Denver had thrown away the negatives for Concern for the City. Luckily I had made six prints at various stages and those were all that were left of the film, so it was important for me to get at least one of those digitized. I’ve learned a lot about preservation and archiving by working with MoMA and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. I have four films already in MoMA’s collection and they recently made a high-resolution digital copy of Concern for the City. Katie Trainor, the film archivist at MoMA, went through all the extant prints and chose an early reversal stock print taken directly from the edited camera original to make an archival digital scan. But Elena Rossi-Snook, the film collection manager for the NYPL, chose for their collection a 1986 print made from an internegative because she loved the vintage Kodak color stock. Carter Haskins, an independent film curator, has been helping me sort through and catalog my films and that has taught me a lot too.

I’ve got a much better sense of myself as a filmmaker now. I can see how much passion I put into my work, which I don’t think I was aware of when I was in the middle of it. If there is a through line I think it has to do with yanking things—whether it’s symbols or places or the viewer—out of context and seeing what’s behind it all. Rimbaud talked about disordering or deranging the senses in order to achieve a sense of true reality and that’s a phrase I was always struck by. Maybe you gotta go a little crazy in order to achieve a sense of serenity.

Peter von Ziegesar, Just Sprouts (16mm, 12 min, black-and-white, sound, 1976). Courtesy the artist.

Peter von Ziegesar, Alaska (16mm, 10 min, black-and-white, sound, 1980). Courtesy the artist.

von Ziegesar at the opening of “Private Lives Public Spaces” at MoMA in October 2019. Photo courtesy Jim Syme.

Cortland Rankin is an Associate Professor in the Department of Theatre and Film at Bowling Green State University. He is the author of Decline and Reimagination in Cinematic New York, which examines cinematic imaginaries of New York’s postindustrial turn from the mid-1960s through the mid-1980s across a spectrum of mainstream, independent, documentary, and experimental films. His work has also appeared in Mediapolis – A Journal of Culture and Cities, Journal of Popular Film and Television, Screening American Independent Film (Routledge 2023), and Hollywood Remembrance and American War (Routledge 2020).

Interview by Cortland Rankin

Disclaimer: This page is for your personal use only. It is not to be duplicated, shared, published or republished in whole or in part, in any manner or form, without the explicit permission of the publisher, author, and copyright holder(s) of the images.